NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

In the 1880s and 1890s, Staten Island was home to some of New York City’s wealthiest families, among them Vanderbilts and Roosevelts, who turned an agricultural community into a sportsman’s paradise, with clubs devoted to tennis, boating, hunting, and bicycling. Among the residents was a young competitive athlete named Alice Austen, the amateur photographer who brilliantly captured the relaxed luxury of the island suburb and much else in the Gilded Age city. In 1945, ailing and destitute, Austen was forced to leave her home and might have died unknown and unappreciated. But the Staten Island Historical Society (today Historic Richmond Town) rescued her photographs—7,000 negatives and prints—and, in 1951, the year before she died, the public finally learned of her work in the pages of Life Magazine. Due to this recognition, her family’s home was saved from demolition and today is a public museum. Alice spent the last 50 years of her life partnered with Gertrude Tate, and in 2017, the Alice Austen House was designated a national site of LGBTQ history.

In 1976, Ann Novotny published the only monograph on Austen, which is long out of print. Last year, the Gotham Center for New York City History, at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, granted me a Robert D.L. Gardiner Fellowship to complete a new biographical study of this pioneering figure. My work expands upon Novotny and will be published by Fordham University Press. One can preview my research and see over 100 photographs from this prized collection in a new digital exhibit just released by the Gotham Center and formally announced here in Untapped New York.

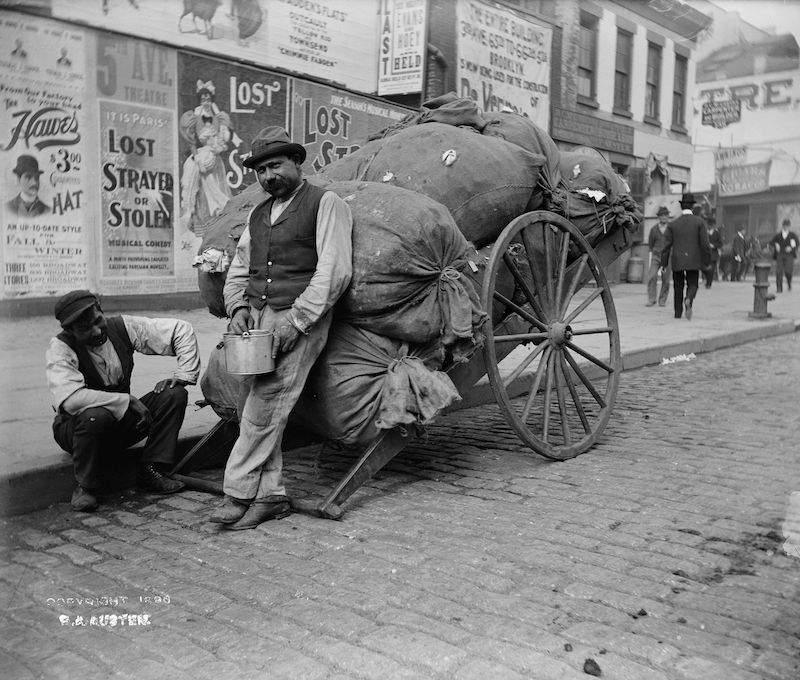

The first group of Austen’s photographs to attract the notice of historians were her “Street Types of New York,” an 1896 portfolio of working class New Yorkers, which immediately drew comparison with Jacob Riis’s and Lewis Hine’s contemporaneous works. All the more notable was that a well-to-do young woman from Staten Island had taken the photographs.

More recently, portraits showing Alice and her friends dressing in men’s clothing or posing as prostitutes have gone viral online. Not only do they upend Victorian gender norms, but they seem to foretell Austen’s lesbian relationship with Tate. Having had access to Historic Richmond Town’s Alice Austen Collection—now digitized and extensively researched by former curator Maxine Friedman—and a cache of letters written to Austen, which belong to the Alice Austen House, I place these images into the larger narrative of Austen’s life.

Austen was a conservative rebel, deeply attached to Staten Island’s high society yet very much a New Woman, physically active and fiercely independent. Born in 1866, she came of age when outdoor leisure activities were the lifeblood of Staten Island’s elite society, and she pursued social status as if it were a competitive sport, collecting her dance cards, newspaper mentions, and tennis scorecards. After a decade of what she called “the larky life,” she came to doubt its ultimate goal—marriage to a suitable man. In 1895, Austen met Daisy Elliott, a Manhattan-based gymnast, ardent feminist and lesbian with whom she had a romantic affair. In 1897, she met Tate, a Brooklyn-born dancing instructor, with whom she shared the rest of her life. When Tate moved to Austen’s Staten Island home in 1917, the women were perceived as middle-aged friends without the stigma that was then growing around lesbianism.

Austen’s photographs of her lifelong friend Gertrude (Trude) Eccleston illustrate her rebellious yet conservative nature.

Trude and Alice grew up together. In this photograph, the two twenty-five-year-olds mirror each other, masked, with their hair down, wearing only their undergarments and stockings, and pretending to smoke cigarettes, looking vaguely like women of ill repute. They stand in Trude’s bedroom in the rectory of St. John’s Church, where Trude’s father was pastor. The church was around the corner from Clear Comfort, the Austen family home.

Alice was very close to the entire Eccleston family, and she often accompanied them on vacation, cameras in tow. In August 1888, she photographed the vacationers at a Lake Mahopac resort, where she was visiting for two weeks. In this sunlit group portrait, Trude and Alice sit in chairs at right. Family friend Charles Barton sits at Trude’s feet, holding her hand. They married twelve years later, but Trude was not interested in him at the time. Prior to Alice’s arrival, Trude wrote, “There is a great dearth of men up here and although every place is full of people they all seem to be old people or very young girls.”

This Clear Comfort photograph shows Trude with her cousin Fred Mercer (at right) and Lieutenant John C. Gregg. Trude had met Gregg at Fort Douglas in Salt Lake City in May 1890, while accompanying her sister Edith on a visit to Edith’s in-laws. Trude described their flirtation to Alice:

This morn. I went for a little stroll with him out to see target practice. He wanted me to fire off one of the guns but they kick so hard that I could not & finally consented pulling the trigger if he held the gun & took aim, this necessitated my embracing him somewhat, well the thing went off and kicked so hard his shoulder hit my cheek & nearly upset me in the arms of another officer. I wish you could have seen the performance, it was great.

Smitten by Trude, Gregg requested a transfer to New York the following summer, when this photograph was taken. During his visit, Alice took the photograph of “Trude & I masked, in short skirts.” Perhaps as relief from Gregg’s high-stakes wooing, Alice and Trude celebrated a moment of rebelliousness. In October, Trude accepted Gregg’s marriage proposal, and they remained engaged for three years until Trude broke off the engagement.

Alice met Daisy Elliott through her enthusiasm for bicycling, a national craze of the 1890s. Alice’s friend Violet Ward wrote the popular guide, Bicycling for Ladies (1896), and Daisy posed for the illustrations based on Alice’s photographs. Nine years older than Alice, Daisy and Alice had a rocky romantic affair. Her last letter, dated January 18, 1898, exemplifies their cat-and-mouse game: “My darling … You have made me believe in your love, you never made it more evident than to-day—and now I am willing to be set aside till you again have time for me.”

In 1897, on vacation with the Ecclestons at Twilight Park in the Catskills, Alice met Gertrude Tate. Alice was 31 and Gertrude 26. Recovering from an illness, Gertrude had lost her hair and wore a wig, which did not stop her from enjoying herself, as this photograph shows. (Gertrude wears a white shirt and dark skirt, Alice a tan, wide-brimmed hat.) After Alice left, Trude wrote to her about Gertrude, whom they had nicknamed “the Chipmunk”: “Hardly any one will be left here after Labor day—the Tates go then. I will miss them so much, we must keep track of the Chipmunk, she is a great girl. She sends lots of love to you & says she misses you more than she can say.”

Gertrude regularly visited Clear Comfort, and between 1903 and the outbreak of World War I, she and Alice traveled to Europe almost every summer. In 1917, Gertrude moved to Staten Island, where the two women lived contentedly until 1929, when Alice lost her inheritance in the stock market crash.

Alice remained close to Trude and other friends from childhood, as this 1930s photograph shows. Seated on the steps of the piazza at Clear Comfort are Alice (front right) and Trude (rear right), who by then had moved from Staten Island to New Jersey. It is likely that Gertrude Tate took the photograph.

Bonnie Yochelson is an art historian and independent curator. She has written books and organized exhibitions on many New York City photographers, including Berenice Abbott, Alfred Stieglitz and Jacob Riis. She completed the aforementioned digital exhibit, “Miss Alice Austen and Staten Island’s Gilded Age,” as part of “Writing the History of Greater New York,” a resident fellowship at The Gotham Center for New York City History, The Graduate Center, CUNY, established by the Robert D.L. Gardiner Foundation. Support was also provided by Historic Richmond Town.

Subscribe to our newsletter