Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

New York City is bursting with colorful displays of public art: the Metronome in Union Square, the Prometheus sculpture in Rockefeller Center, and the playful Alice in Wonderland statue in Central Park. Whether it is a permanent monument or an immersive pop-up installation, New York’s public art enhances the quality of life for residents and tourists alike, adding a touch of wonder, whimsy or beauty to an ordinary commute. Public art can also serve as a monument to bygone times, surprise or entertain viewers, or prompt passersby to ponder a provocative social or political issue. Beyond the iconic, however, New York is also home to a wide range of hidden art installations that reward those lucky enough to spot them. Whether they’re well-kept secrets among longtime residents or reveal themselves only to the most observant passersby, these 10 hidden displays of public art delight and entertain New Yorkers every day.

Nestled into a fenced-in plot on the corner of LaGuardia Place and West Houston is an unexpected remnant of New York’s botanical history. At first glance, the overgrown green space might appear to be an ordinary city garden or vacant lot. But the 1,000 square foot plot is more than a patch of wild space — it’s a piece of living art installed in 1965 by Land Artist Alan Sonfist who called itTime Landscape. The work transposes a slice of Manhattan to its pre-colonial past, representing the indigenous forest that would have flourished long before the area was settled by the Lenape and European immigrants.

Sonfist’s recreation of the old-growth forest is a window into the past, featuring a grove of beech trees transplanted from saplings in the Bronx and a forest of red cedar, black cherry, and witch hazel. The northern patch of land is a mature woodland dominated by oak trees, white ash, and American elm, which have grown from the saplings Sonfist planted 57 years ago. Virginia creeper, milkweed, aster, and pokeweed cover the ground, providing a haven for local wildlife as well as a glimpse into Manhattan’s forested past. Land Artists hoped to change the landscape of public art by unexpectedly transposing nature into urban space, an early example of ecological activism. Agnes Denes’s Wheatfield — A Confrontation (1982), for which the artist planted a 2-acre wheat field on a landfill in Battery Park, is another example of an unexpected encounter with the wilderness on the streets of New York.

Beneath the bustling sidewalks of Herald Square, along the platform of the 34th Street N/R subway line, a hidden art installation awaits. A row of ordinary green ducts disguises an immersive auditory experience — Christopher Janney’s 1995 sound installation Reach. Commuters waiting for the train are often surprised by a melody of nature and instrumental sounds that mingle with the noise on the platform, transporting them to another time and place.

Motion sensors are concealed within the eight “eyes” of the ducts, activating sounds that disrupt the hustle and bustle of the station. Flutes, marimbas, animal calls, and immersive soundscapes evoking far-flung locations like the Everglades or the Amazon rainforest soothe and entertain busy commuters. Each eye vocalizes a different sound, which blends together into an interactive, multilayered symphony. The sounds are updated every year to create an evolving dialogue between the station’s two platforms and between commuters and the urban environment.

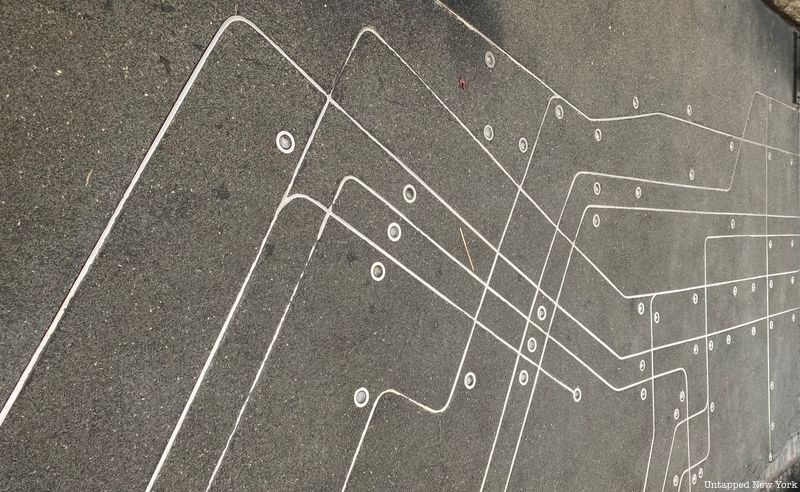

Francoise Schein’s Greene Street installation is often overlooked by passersby — it’s literally under their feet! The brass sculpture Subway Map Floating on a New York Sidewalk was commissioned in 1985 by real estate developer Tony Goldman, who wanted to beautify the area in front of his building. Set directly into the Soho pavement, the installation invites pedestrians to follow the twisting lines of the subway system with their feet.

The sculpture’s bending 90-foot rail lines do not faithfully replicate the MTA system; instead, they stretch and twist fantastically like veins flowing through the human body. At night, the sculpture is illuminated with LED lights embedded in the basement ceilings of adjacent buildings, bringing the sparkling installation to life. Beaming into the darkness, the map is an astonishing sight on the nocturnal streets of Soho. For over 35 years, it’s been a shining beacon of public art hidden in plain sight, enhancing the journeys of those lucky enough to spot it.

Keith Haring’s iconic stick figure art may sell for millions today, but on some walls, overpasses, and public buildings around New York City, his drawings can still be viewed for free. One of these is his 1987 mural at the former Carmine Street Pool, now the Tony Dapolito Recreation Center, in the West Village. As legendary DJ Junior Vasquez performed in the August heat, Haring painted a massive poolside mural above the heads of local swimmers.

The mural was created at the height of Haring’s career, only a few years before his tragic early death from AIDS. However, Haring continued to give back to the local community until he died, with the lifelong intention that his art would make people happy. He has said that painting the 170-foot mural was “one of the most incredible situations” of his career, and his dancing dolphins, fish, and mer-creatures continue to enchant and delight swimmers today. New York’s free public pools are one of the city’s truly democratic locations, where people from all walks of life come together for exercise and recreation, ensuring that the public can continue to enjoy Haring’s art for years to come.

Now in its 45th year, Max Neuhaus’s sound installation Times Square (1977) is hidden under the subway grates of the pedestrian island on Broadway between 45th and 46th Streets. Above the noise and clamor of Times Square, visitors may notice the sound of a low drone and buzzing bass contrasting with the noise pollution of the busy center. The installation is purposely concealed to reward observant listeners, without a sign or marker alerting passersby to its existence. Unfortunately, this unique feature has its drawbacks — some tourists have mistaken the noise for a stalled train or detonating bomb!

After the soundscape’s initial installation from 1977 to 1992, it became permanent in 2002 with a grant from the Dia Foundation. It now operates 24/7, emitting an eerie hum that counteracts the sensory overload of the square. The effect is disorientating, setting listeners at odds with the overwhelming hustle and bustle of the city. Tourists during rush hour react with surprise to the unexpected noise, while late-night visitors can hear the sound buzzing in the silent square. During Times Square’s seedier era in the 1970s, before it became the tourist trap we know today, the soundscape would have been even more startling to unsuspecting visitors.

One of the better-known artworks on this list, Earth Room (1977), is nonetheless hidden away from the public eye in a darkened Soho loft. Open to the public for free from autumn until spring, Earth Room lives up to its name as an installation of 280,000 pounds of dark soil, piled to waist height. Covering 3,600 square feet of space, Earth Room is overwhelming in its vastness, swallowing up the noise and light from the street outside.

In addition to the sight of yards of undisturbed soil, Earth Room is also a powerful olfactory experience, transporting the visitor to an agricultural setting. It’s a welcome interruption from the crowded city streets, and an indirect challenge to the consumerism and fast-paced real estate development of Soho today. Every summer the installation is closed for cleaning and maintenance in order to preserve the original soil Walter de Maria planted 45 years ago. Another one of his installations, Broken Kilometer (1979), consists of five rows of five hundred shiny brass rods and can be viewed for free year-round a few blocks away.

Visitors can enjoy a fine dining experience along with their art viewing at the Hotel des Artistes restaurant. Designed in 1918 by George Mott Pollard as an experiment in collaborative artistic living, artists lived and worked in the studios upstairs and dined in the downstairs Café des Artistes. This fusion of work, life, and entertainment proved to be immensely popular and was enjoyed by artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Rudolph Valentino, and Norman Rockwell.

Now, visitors can enjoy the golden age of Art Deco by experiencing an astonishing glimpse of old New York. Diners eat under the restaurant’s nine murals painted by former resident Howard Chandler Christy, one of the most popular portrait painters of the Jazz Age. Fantasy Scenes with Naked Beauties was completed upstairs in the artist’s studio from 1928 to 1935, featuring nymphs and mythical figures playfully frolicking in nature.

Tucked away in the gated public park across the street from the Stonewall Inn, George Segal’s Gay Liberation Monument (1980) is likely to go unnoticed by many Pride Parade participants or passersby. However, the monument has significant hidden history — it commemorates the 10-year anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, the beginning of the gay rights movement, and is the first piece of public art dedicated to LGBTQ+ rights. The sculpture was commissioned by the Mildred Andrews Fund in 1979, at a time when the public representation of gay people was still deeply controversial.

In Segal’s signature white-painted style, the monument depicts two male statues chatting, while two seated female statues converse on a nearby bench. The casual nature of the monument embodies the funder’s request that the piece “had to be loving and caring, and show the affection that is the hallmark of gay people,” as well as equally represent men and women. Deemed too controversial for its intended location, the sculpture was instead installed in Madison, Wisconsin from 1986 to 1991. It was finally moved to Christopher Park in 1992, where it remains a centerpiece for New York’s LGBTQ+ community today.

J. Seward Johnson’s 1982 sculpture Double Check is less notable for its subject than for its accidental involvement in one of the darkest days of New York’s history. Johnson became famous for his life-size bronze statues of ordinary people, and his sculpture of a seated businessman searching his briefcase is a quintessential representation of 1980s Wall Street. It depicts the figure double-checking his files, oversize calculator, and tape recorder before heading into a meeting.

The inconspicuous statue later became an impromptu memorial when it survived the nearby September 11 attacks. The life-like sculpture was found covered in debris, initially confusing first responders searching the rubble for survivors. After returning to Johnson’s studio for safekeeping, Double Check was reinstalled in Zuccotti Park still bearing dents and scratches as a memorial to the tragic event. It has since been moved a block away and bears a commemorative plaque chronicling its significance during the attacks.

Many large corporate headquarters feature displays of public art in their lobbies, and KPF Architects at 505 Fifth Avenue is no exception. Rather than an eye-catching painting or sculpture, however, the artwork is integrated into the lobby itself. Fans of James Turrell’s immersive light installations will enjoy the chance to experience Plain Dress (2005), a site-specific piece that visitors experience by walking through on their way to the elevator. The collaboration was inspired by a comment from one of the architects, who said that the lighting in the building’s half-finished lobby reminded him of a Turrell exhibition.

Turrell is renowned for his glowing exhibitions that play on light and space and often encompass entire buildings or rooms. He transformed the lobby into a forced-perspective lightbox that changes color 24 hours a day, with LEDs throwing pink and blue light onto the white plaster walls. The colors shift frequency and mood depending on the time of day, reflecting the bustling chaos of Fifth Avenue outside. The three-dimensional light sculpture transforms itself over the course of the day, making multiple visits worthwhile.

Next, check out the best public art installations to see in October 2020!

Subscribe to our newsletter