Exclusive Gilded Age Arts Society Debuts New Public Exhibits in NYC

The American Academy of Arts and Letters, a venerable New York cultural institution, is a portal to art across time!

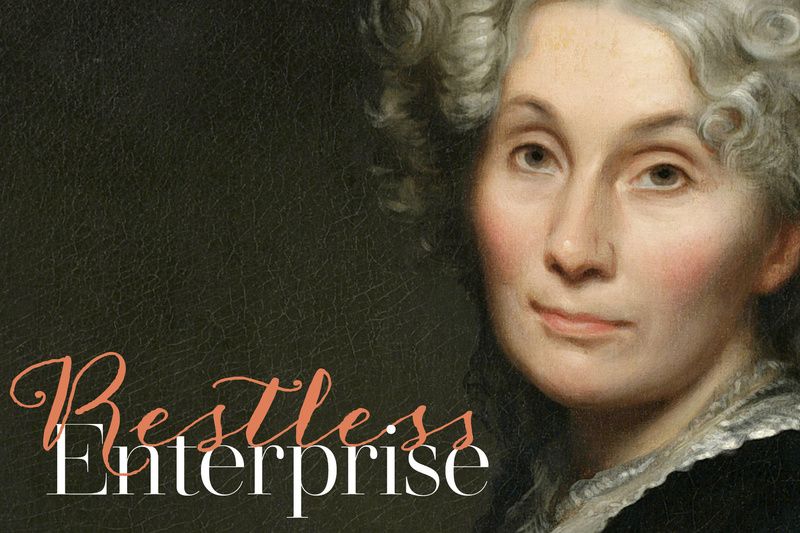

If you’ve lived here for more than a New York minute, chances are good that a place you loved–a shop, sign, view or building–has been closed down, torn down or covered up. But it probably won’t surprise you to learn that New Yorkers have been lamenting the loss of beloved landmarks for generations. One such New Yorker is profiled in a new book, Restless Enterprise: The Art and Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex, by Katherine Manthorne, an art history professor at The Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Greatorex documented old buildings, landmarks and churches in the years after the Civil War, when New York was going through a building boom. You can learn more about Greatorex and her work in our upcoming book talk with Katherine Manthorne!

Some of the demolished structures that fell during the post-Civil War building boom dated to the Revolutionary War era. Greatorex’s drawings symbolize her grief over their destruction. She eventually published a collection of her pen-and-ink drawings called Old New York: From the Battery to Bloomingdale as a folio volume in 1875, with text by her sister.

One of Greatorex’s most hallowed sites was the North Dutch Church on Fulton Street. It was one of the city’s oldest churches, dedicated in 1769, and had been used by the British during the Revolutionary War. When its demolition was announced in 1866, Greatorex drew a picture of it, later returning as it was being torn down to paint it. She took a panel from the pulpit as a memento and for use as her canvas, writing on it: “Built in 1767, demolished in 1875.” That terse but plaintive inscription, Manthorne says, was as much a protest as it was documentation. The painting was shown at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia and is now in a private collection; the drawing is in the Museum of the City of New York’s collection.

Trinity Church’s St. Paul’s Chapel, where George Washington worshipped on his Inauguration Day in 1789, is famous for having survived 9/11. But another of Trinity’s chapels, St. George’s, did not even survive to the 20th century. It was built before the Revolution with a 172-foot multi-tiered steeple and a capacity of 2,000 worshippers. Greatorex painted it in 1868 before it was demolished. Greatorex also sketched Old Tom’s Tavern, a hangout for writers on Thames Street west of Broadway. Old Tom’s may well have been New York’s original dive bar; Greatorex’s interior view depicted its famous layers of hanging cobwebs.

Not every place Greatorex drew was swept away. For example, the Morris Jumel Mansion has been preserved as a treasured Manhattan landmark dating to 1765. In another case, though, her depiction served as a memorial to something she had no way of knowing would be destroyed. She sketched a pear tree said to have been planted by Governor Stuyvesant during Dutch colonial times, but by the time her book was published, “the tree had been knocked over by a passing carriage,” Manthorne writes. “Such incidents only strengthened the artist’s resolve to record what she could of the old city that was fast disappearing.”

Learn more about Eliza Greatorex and her quest to save old New York in our upcoming book talk with Restless Enterprise author Katherine Manthorne on Wednesday, March 31st! Tickets for this talk are just $10, or gain access to unlimited free virtual events per month and unlock a video archive of 100+ past events as an Untapped New York Insider starting at $10/month. Already an Insider? Register here!

Rediscovering Old New York

Next, check out The Oldest Buildings in New York’s Five Boroughs

Subscribe to our newsletter