100th Anniversary Great Nave Tour at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

Celebrate the 1925 construction of the stunning nave inside the world's largest Gothic cathedral!

While many remember Ellis Island as the “island of hope,” for others, it was “the island of tears.” For half of the 20th century, Ellis Island served as a detention center for unwanted immigrants who were mentally or physically ill and travelers whose backgrounds, connections, and nationalities made them suspects of crime and radical political beliefs. One the little-known detentions that took place at Ellis Island happened during World War II. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese and Japanese Americans were detained at Ellis Island under the orders of the FBI and Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, to be “held in custody indefinitely.” While the more infamous Japanese interment occurred on the West Coast, this footnote of history on Ellis Island has mostly been forgotten.

Ellis Island’s transformation into a detention center started out gradually. From its establishment in 1890, and for about the next twenty years, Ellis Island was a brief stopping point for immigrants: they would be processed and swiftly welcomed into the United States to set up their new lives in the city or travel across the country to another state. In those first few years very few immigrants were detained and those that were, were held back to prevent the spread of diseases such as measles and tuberculosis. Patients would be moved nearby buildings to be isolated on the south side of the island. Although there were some travelers who were detained for suspicious political and criminal activity, detainment for fear of communism and treason did not become rampant until the World Wars.

Ellis Island Immigration center entrance. Image from New York Public Library

During World War I, nativist sentiment increased and led many Americans began to believe those with ties to another country made them traitors to the U.S. The Immigration Act of 1917 established a literacy test for all entering immigrants. In a 1919 speech, President Woodrow Wilson stated that “Any man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready.” German civilians who happened to be in America or in American territory in the Panama Canal zone when the United States entered World War I were detained at Ellis Island, before being relocated to a camp in Madison County, North Carolina and later to another location in Georgia. The U.S. government labeled the detainees as “enemy aliens.”

According to this encyclopedia on World War I, the United States also tried to convince other countries to intern German citizens: “Here, as in Britain and Australia, the reinforcement of racial hierarchies in the colonies and the metropole went hand in hand with the isolation and expulsion of German nationals. The United States was also accused of pressuring the governments of Cuba and Peru to introduce internment measures there.” It also took an extended period of time after the war ended to fully repatriate the Germans, which was not complete until March 1920. In 1921, the Quota Act limited the percentage of immigrants from each country who were allowed to enter. Those that immigrated after the quota of their country was met were detained until they could be sent back to their country of origin.

Immigrants arriving at Ellis Island. Image from the Library of Congress.

In addition to anti-foreigner sentiment, the U.S. experienced its first “Red Scare” starting in 1919 which saw the rise of mass labor unions connected to socialist and communist movements. Those suspected of striking with labor organizations and having ties with radical political groups were rounded up and detained at Ellis Island.

Life in detention was mundane. Ellis Island was equipped with a laundry room, post office, and other small amenities. Writer C.L.R James had enough time on his hands to complete an entire book: Mariners, Renegades & Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and The World We Live, a book analyzing Melville’s Moby Dick. Still, people were often confined to overcrowded, unsanitary conditions, and left with poor food and inadequate medical care.

Upon arrival, immigrants were served meals in a dining hall. Image from New York Public Library

During World War II, the detention centers of Ellis Island not only detained Japanese New Yorkers, but also war prisoners, approximately 7,000 incomers with German, Japanese, and Italian backgrounds were detained out of the suspicion that they were enemies of the United States. German men were rounded up and sent to Ellis Island prior to deportation. Some remained at Ellis Island for only a month; others remained for up to two years. By June 1944, only one Japanese American had not been transferred out of Ellis Island.

During the Cold War, fear of communist influence in the U.S. once again raised concerns over incoming visitors and immigrants from Europe. In 1950, the Internal Security Act permitted the denial of any alien who had connections to totalitarian or communist groups. That same year, Hungarian violinist Joseph Sziegti was detained at Ellis Island despite having previously performed in the U.S. dozens of times. His fame and publicity drew criticism of his detainment, which forced U.S. officials to release him after a few days. French scientist and good friend of Albert Einstein, Irene Joilot-Curie (the daughter of Marie and Pierre Curie) was also detained but immediately released after the demands of Einstein and other scientists.

About 12 million immigrants passed through Ellis Island. Image from the Library of Congress.

Ignatz Mezei and Ellen Knauff, of European descent and both married to Americans were barred from entering the country. Knauff had escaped Czechoslovakia during World War II but accused of subversiveness upon arrival. Although Knauff was able to prove that accusations were false and the accusations against Mezei’s communist activities were extremely vague, both were detained at Ellis Island for several years.

In response to public pressure, in 1952, the McCarran-Walter Act declared that detention would be a rare exception, and that instead, aliens who posed security risks would be under parole. In 1954, attorney general Herbert Brownell, Jr. announced the closure of Ellis Island. However, the end of Ellis Island was far from an end to wrongful incarceration and discrimination against aliens.

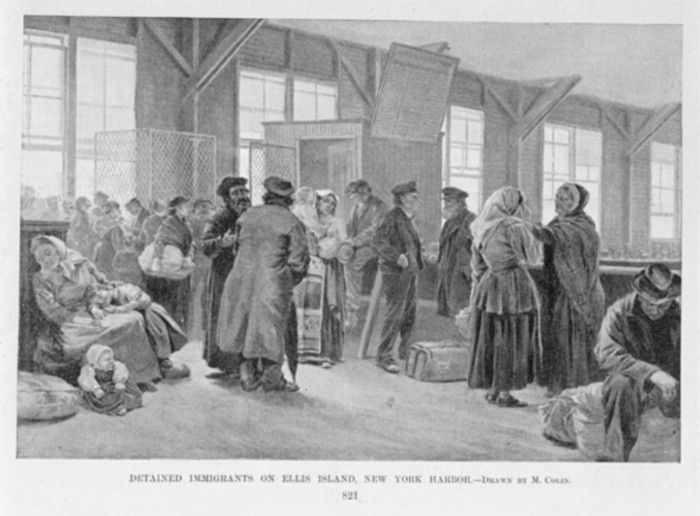

A sketch of detained immigrants at Ellis Island. Image from New York Public Library.

New York City today may not have Ellis Island as a detention center. But there are still facilities in the United States where immigrants and refugees are detained. Today, Ellis Island may be an explorative museum children and adults can enjoy. But its dark past will remain an essential part of both New York and American history.

Next, check out the top 10 secrets of Ellis Island.

Subscribe to our newsletter