Vintage 1970s Photos Show Lost Sites of NYC's Lower East Side

A quest to find his grandmother's birthplace led Richard Marc Sakols on a mission to capture his changing neighborhood on film.

Untapped New York is excited to partner on an editorial collaboration with the Gotham Center for New York City History. In this series, we’ll share fascinating stories from the Gotham Center Blog archives. These scholarly articles will explore New York City history through a variety of lenses and cover topics that range from Dutch colonialism to modern art!

Conflagrations loom large in the memories of cities. In addition to the horrific loss of life and property they entail, these catastrophes often bring about periods of rapid and transformational change. Rome’s burning in 64 AD destroyed the chaotic republican city and made room for imperial grandeur. The Great Fire of London in 1666 saw a medieval warren of closely-packed wooden buildings, muddy lanes, and open workshops replaced by a grid of wide paved streets, stately stone townhouses, and towering church spires. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 wiped away a rough-and-tumble frontier town and put in its place a cosmopolitan metropolis that by the turn of the twentieth century had become a symbol of American cultural and industrial power. In each case, fire marked epochal transformation both in the cities’ larger function and how their populations experienced the built environment.

For the historian, disasters are not only important as notable events but also for the insight they provide into urban life in the past at levels not usually visible. Investigations into a blaze’s causes, the loss of lives, and the extent of property damage yield great volumes of official paperwork, as do plans for re-building. Criminal interrogations, witness statements, and insurance and poor relief claims – when they survive — mean that even members of society whose voices usually remain silent are brought into sharp relief by fire. As a result, we know a great deal more about the lived urban experiences of first-century Rome, Restoration London, and Gilded Age Chicago than many other times and places.

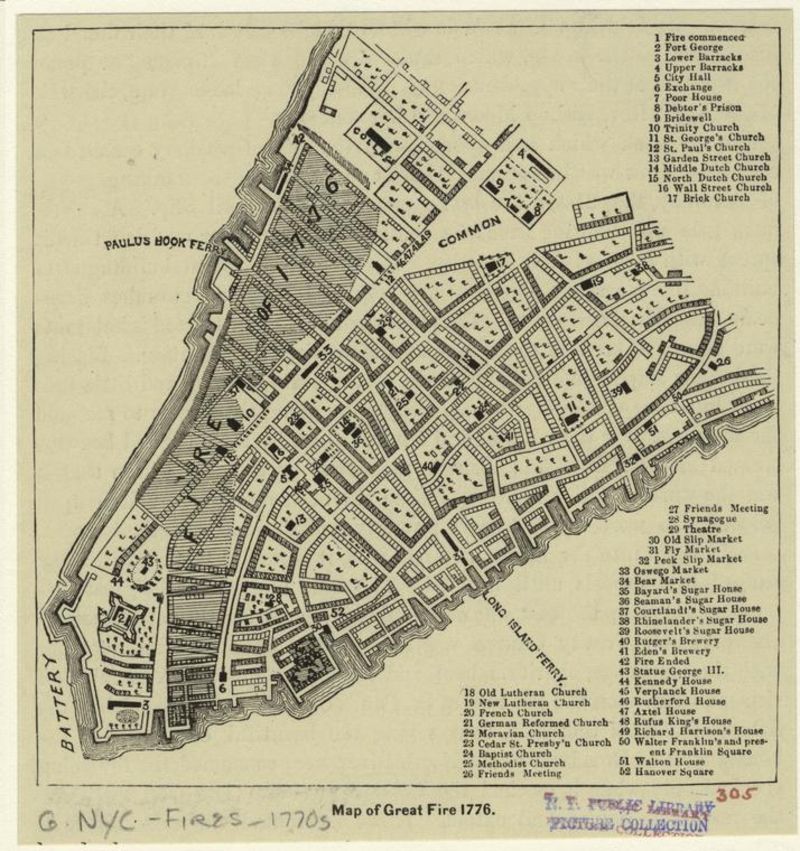

Modern-day New Yorkers are less likely than Romans, Londoners, or Chicagoans to believe that a landmark inferno shaped their city’s history, but Brooklyn College historian Benjamin L. Carp contends that a prodigious blaze did indeed transform Gotham amid the tumult of the American Revolution. The Great New York Fire of 1776 reconstructs a little-remembered catastrophe that re-shaped New York’s politics, society, and economy. The fire, which came on the heels of the British conquest of Lower Manhattan island, killed hundreds, burned about a fifth of the buildings in the city, and created long-lasting housing and food crises for thousands of civilians and soldiers. In the aftermath, British, Continental, and New York authorities blamed one another for the conflagration as ordinary people sought to recoup their losses, rebuild their lives, and take advantage of opportunities opened by the destruction. Both processes, documented unusually well in the wake of the catastrophe, reveal the fissures and contradictions at the heart of the revolutionary experience. Often, the experiences revealed do not fit the oft-remembered image of a people fighting for the “lofty principles of liberty, equality, and unity” (5); one reason that later historians underplayed the significance of the fire. But, as Carp persuasively demonstrates, “collective violence and destruction” (5) were part and parcel of the revolutionary movement, and The Great New York Fire uses a unique incident not just to tell a new story about early New York City but to “reveal something about the untold scope of a radical revolutionary movement” (123).

Centering the question of who started the inferno and why, Carp draws on a wealth of sources to craft an engaging narrative of events and conditions leading up to the fire, to reconstruct the night of the blaze itself, and to parse the various investigations, interpretations, and accounts afterward. Building on and expanding a 2006 article in which Carp investigated various accounts of the causes of the fire, The Great New York Fire is intended for both scholars and a general audience. The text reads as a page-turner, effectively combining a whodunnit with a sociological study and a reflection on the collective violence inherent in revolution. In short, pithy chapters, Carp tests and discards various theories about the fire’s origins and progress – ultimately deciding that the blaze was most likely “the intentional work of perpetrators with political motivations – the more radical elements of the rebel coalition” (2). Still, “[t]he Great Fire of 1776 was a nameless deed” (4), and the historical record yields no definitive answers. However, as is often the case, the investigation itself yields novel and unexpected insights into the time period.

By parsing various attempts to assign blame and conducting his own arm-chair investigation, Carp reveals something rather more interesting than the name of a culprit: a city and its people beset by the complex, ambiguous, and often unattractive elements of an ongoing revolutionary struggle. In the book’s opening chapters the reader is thrust into the chaos of the early days of the Revolution, finding New York City’s streets divided between a large faction of loyalists, a small number of committed radicals, and a relatively moderate majority. At higher levels, revolutionary and loyalist leaders jostle with colonial, provincial, Continental, and imperial governance in overlapping and complicated ways. As the action picks up in the summer of 1776, Carp narrates the debate over burning New York City in advance of the British conquest, weighing the opinions of Congress, George Washington and his nascent Continental Army, and New York’s incipient revolutionary government, all of whom ultimately decided against setting the fire. Yet, as Carp demonstrates, these authorities were so tenuous and overlapping that, even if no leader signed an order for the city’s destruction, all of these parties bore some responsibility for the event.

The fire’s aftermath yields new insights into the tumultuous experience of Revolution. A diverse assortment emerges in Carp’s description of the Great Fire of 1776 and its aftermath: many of those caught up in the investigation were Black or mixed race, and at least one person suspected of starting the blaze was likely a female sex worker. In addition to joining in on the ignition of the fire, women play a major role in the text as witnesses, survivors, and agents in re-building the city, demonstrating the ways that they shaped the revolutionary experience in ways that don’t often emerge at the level of high politics or military analysis. Even as the fire blazed, British and loyalist soldiers and civilians carried out summary executions of a dozen or more suspected arsonists, often throwing their bodies into the fire, sparking accusations of atrocities against civilians that would dog the king’s army for decades. In one especially brutal case, soldiers attacked a potential incendiary and “ran him through with their bayonets” before “hanging him ‘without ceremony’ by the neck” (135-36). A clean and orderly war this was not.

Efforts to investigate the Great Fire of 1776 exposed the fissures at the heart of the War for Independence. Rivalries between states appear early and often, as soldiers from New England bore the brunt of the blame for the fire on both sides, reminding the reader of the mistrust that persisted between regions within the revolutionary coalition. Religion played a divisive part as well, as loyalist Anglicans blamed rebel dissenters for burning Manhattan’s Trinity Church, one of the grandest Church of England outposts in North America. Print media emerges as one of the most important factors in shaping the narrative of the fire and its significance to the overall war, with loyalist and British papers churning out graphic depictions of destruction and ruin while rebel polemicists focused on the atrocities of British soldiers in the wake of the blaze. In these pursuits rumor and fabrication had as much or more of an impact on public opinion than the facts of the case. Media as well as memory of the blaze fueled an ever-increasing cycle of tit-for-tat revenge that lasted until the end of the war, after which Carp argues convincingly that, for many of the victorious revolutionaries, the fire was best forgotten in the interests of promoting peace and the re-integration of former loyalists.

The Great New York Fire of 1776 makes us rethink many of our assumptions about the American Revolution and New York City’s role in it. Carp presents the reader with a violent, confused account of the Revolutionary War. Instead of virtuous revolutionary leaders, we find rebels who “skulked and deceived, burned and massacred, unleashed campaigns of terror, and denigrated people as less worthy of citizenship,” among other sins (5). It is not a story that lends itself to nationalistic pride or heroic memorialization. It is, however, one that includes many more voices from a much more varied and diverse set of people than most influential histories of the Revolution present, and it is one that has a distinctive resonance with the era of confusion and political violence in which many Americans now find ourselves. In that sense, it is a peculiarly New York story – that of a vibrant city divided, destroyed, and rebuilt by its resilient population in defiance both of revolutionary and British designs. Carp’s book thus offers a valuable lesson to both the city and the nation as a whole.

Donald F. Johnson, Associate Professor of History, North Dakota State University, is author of Occupied America: British Military Rule and the Experience of Revolution (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

Next, check out The Great Fire of 1845

Subscribe to our newsletter