Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

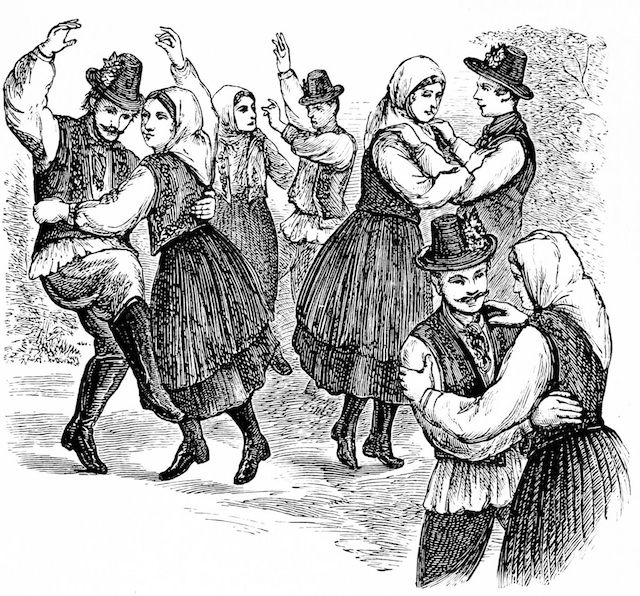

Csárdás, a Hungarian Folk Dance. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

Csárdás, a Hungarian Folk Dance. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

Zoli has the broad biceps of a wrestler, the burly upper body of a man who chops wood and lifts heavy objects for a living. He’s medium-height, with a thick goatee, and his hair is trimmed down to a uniform millimeter. There is a striking intensity in the way he speaks, cupping one hand over the other, elbows resting thoughtfully on the armrests of his chair. A common resident of Budapest, Zoli is far from average. Not a philosopher by profession, he is certainly one at heart. He’s a well-researched, somewhat solemn individual who has spent a great deal of time reflecting on where he fits in his society at large.

“Culture,” he says in Hungarian, “is continuity.” He does not speak English, and so my husband translates. He’s very vocal about his view that Hungarian culture is thinning out, that it’s slowly fading against the force of western (particularly U.S.) values that are now becoming prevalent in Hungary. So, to better understand what’s being lost, I ask him to list out aspects of culture that are quintessentially Hungarian. But it’s not so easy. He feels it’s important that we start at the beginning and that we clearly define culture.

“People loosely pull their definitions from a Wikipedia article,” he says. “But to me, culture is when a baby is born. The infant scans his surroundings, absorbing behaviors, values, and boundaries. Culture is how a family helps this child to get around in the world. Culture is how and why it’s worth living in any particular environment. And as it is true for the baby and its family unit, it is also true for larger communities. Culture is information passed through generations. The older the community, the more a person knows about the world. Very importantly, strong, surviving cultures teach how to live with others, not at the cost of others.”

I know that Zoli is disappointed and frustrated. There’s a bit of regret in his tone when he expresses that this definition is not as strongly applicable in modern times. “Today everything is for the moment,” he says. “The architecture, the food, the music. None of it is lasting. A hit song from a popular artist is forgotten in two weeks. There’s no longevity. We’ve lost our sense of value.”

In today’s modern world, we desire something new, all the time. But what of our old ways, which are, according to Zoli, the heart of culture? Personally, as a U.S. citizen, I don’t feel I have any old ways. My mom is Irish/German/Austrian, my dad a Punjabi Sikh from Fiji. My personal history is a confusing mix of all those cultures, superficial bits and pieces: weddings, an occasional baptism or visit to the Sikh temple, mixed in with hamburgers, amusement park visits, shopping at popular chain retailers, and bachelorette parties in Vegas. It’s not the whole story. I don’t know the whole story. Of any of it. Of course, it’s there. Whatever our country or our ethnic background, we all have culture. Yet we’re distracted, and more often than not, we’re no longer inclined to learn about it. It seems as though a similar dilution of culture is what Zoli sees happening in Hungary.

Hungarian culture is simple, he says, finally answering my question. “It’s our folk songs and tales that tell us about the past. It’s our language, which does not merely transfer information, but carries the past within it. This is very different than English, which has changed so drastically in the last several hundred years you need a degree to read Shakespeare. Hungarian culture is knowing how to cut grass with a sickle. It’s using a whip, not to harm or tame creatures as in other societies, but to cleanse the air with it’s cracking sound. It’s horse riding, shooting bows and arrows, farming, embroidery, and village life. It’s sitting in the backyard, teaching yourself how to play an instrument, and if need be, it’s the willingness to stand up, reshape your sickle into a spear and fight to protect all of it.”

Zoli with a typical Hungarian folk art design tattooed on his arm

Zoli with a typical Hungarian folk art design tattooed on his arm

But today, it’s harder to fight. No longer victim to the many dictatorships of its past, the current threat to Hungarian culture is insidious. It’s based on a U.S. and western lifestyle that has slowly permeated this country with fast food chains, pop music, cheaply constructed apartment complexes, and an abundance of shopping malls. The privileged few of this country spend their earnings on clothes and pedicures while Budapest’s world-famous opera house is talking of closing its doors because there is not enough money to sustain it.

“The fundamentals of Hungarian culture are rooted in rural society,” Zoli says. “It’s then brought to the city where it’s lost. The intellectual, prosperous people of the city should help to maintain and preserve our culture. Yet instead, this trend is working it’s way backward into the villages. Many villagers now neglect their land to shop at Tesco [the equivalent of Wal-Mart], because it’s easier than working the land.”

Still, Zoli believes some of what was lost is coming back. The Hungarian spirit called pálinka (a fruit brandy, commonly made with plum) was suppressed by the Russians for fifty-five years, but is now regaining popularity. And learning the art of the bow and arrow is again a source of cultural pride in the wake of socialism. Indeed, I saw a teenager on the underground wearing shorts, T-shirt, and sneakers, carrying around a large bow, like he was on his way from or to shooting lessons.

“The key,” Zoli says, “is not to let any of it become too commercialized.” I understand. Capitalism is a serious source of devaluation. Big companies step in and cheapen everything to make a quick buck, as is already happening with some brands of pálinka.

He finishes by telling me, however, that the more intensely a culture is stifled and the more powerfully it is repressed, the more passionate the resistance. Perhaps he’s right. People like Zoli will always be around, making clear what could be lost, branding their roots on their forearms in a beautiful, traditional swirl of folk art. He knows a great deal about the etymology of his language. He knows his folk tales and his history in great detail, and he’s happy to share.

Subscribe to our newsletter