Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Untapped New York is excited to partner on an editorial collaboration with the Gotham Center for New York City History. In this series, we’ll share fascinating stories from the Gotham Center Blog archives. These scholarly articles will explore New York City history through a variety of lenses and cover topics that range from Dutch colonialism to modern art!

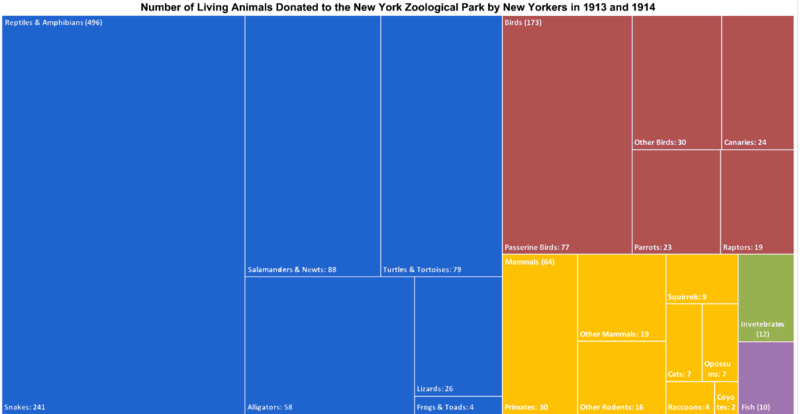

From 1899 to 1914, people around the world gave over 12,000 animals to the New York Zoological Park in the Bronx (almost 5,000 of them were snakes). Donations to the zoo fulfilled two purposes: they supplied the zoological park with more animals, and, perhaps more importantly, helped the zoo form a relationship with certain communities around them. This project is a focused look at a section of these animal donors, the people of New York City. What creatures did New Yorkers give to the zoo, and where did they get the animals? Who took the time to convey a captured opossum, a single pigeon, or the occasional coyote to the Bronx, and why? My goal is to try and understand what the archival record of animal donations can tell us about the way people in the city related to the animals around them, and to the new zoo.

Many of the animals donated to the zoo were common in the New York City area — robins, turtles, raccoons, and unwanted household pets that were ferried by subway, on foot, and through the mail to the gates of the park. By mapping what these animals were and who donated them, I hope to shed some light on why the zoo might have accepted them into their otherwise more internationally-sourced collection.

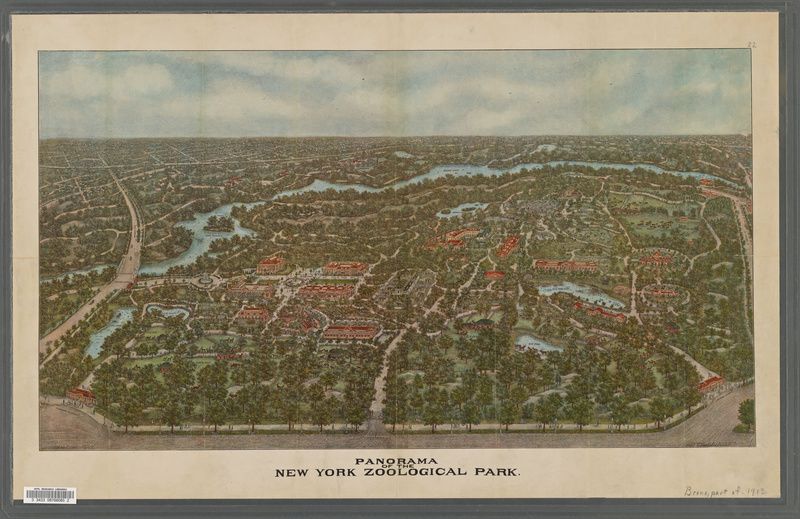

Ostensibly designed to teach city-dwellers about nature, the Bronx Zoo took 261 acres of land used by local residents for hunting, foraging, and recreation, and turned it into a patchwork of manicured lawns dotted with neo-classical buildings and animal cages. When the zoo opened in 1899, the founding administration characterized the Bronx park as doing for nature what the Metropolitan Museum did for art or the American Museum of Natural History for the natural sciences — it would bring nature’s “wonders and beauties within reach of thousands and millions of all classes who cannot travel or explore”.[1] William Hornaday, the zoo’s director from 1896 to 1926, purchased most of the zoo’s animals from a robust network of collectors and dealers who operated in the western United States and colonially-occupied regions of Africa, Central and South America, and the Caribbean. How did animals found in New York City fit into the more globally-oriented scheme of Bronx Zoo planning? This digital humanities project is a first look at how the zoo used these gifts to form relationships with potential patrons, the zoo-going public, and urban animals.

What follows is a product of the COVID-19 pandemic, in both archival content and format. When New York City, where I live, went into various phases of lockdown and I could not focus enough to write my intended dissertation on the global context of the Bronx Zoo and the history of ecology, I took an obsessive dive into digital sources. The archival core of the project is a handful of documents I was able to gather before libraries were shuttered: the New York Zoological Society’s records of “Gift Acknowledgements” from 1913-1914, held in the Wildlife Conservation Society Library and Archives (the New York Zoological Society changed its name to the Wildlife Conservation Society in 1993). These files list the name of each donor, the donor’s address, and the animal(s) given. Zoo administrators used this information to thank each donor personally with a letter, and to publicly recognize their contribution in the Society’s Annual Report.

To contextualize these Bronx Zoo donations, I used historic insurance maps and GIS software to plot all 342 New York City donors from 1913 and 1914 onto a map of the metropolitan area. After placing the donors (and the 785 animals they gave) into the city where they lived, I then cross-referenced each person with census data, historic city directories, digitized newspaper articles, scientific articles, and nature guides. The result is a series of maps that reveal relationships between the Bronx Zoo and certain neighborhoods, between multiple donors, and between animals and the physical layout of the city. You can see and interact with these maps on the original post in the Gotham Center blog.

This project is a facet of my more extensive research on the logistics of animal collection and display. Zoos are institutions with complicated (and often concealed) ties to politics, environmental care, and ideas about the natural world. My goal is to piece together the role zoos in the United States played in shaping ideas about race, immigration, gender, and U.S. territorial expansion. In tracing the animals gifted to the zoo, I hope to add to scholarship that interprets nonhuman animals as individuals with their own histories, instead of abstractions that represent an entire species or region.[2]

Well-timed technical and financial support for this project was provided by a grant from the Polonsky Foundation-NYU Digital Humanities Internship Program.

The brown thrasher Mr. L. Def. Downer donated to the Zoological Park might have originated in Tompkins Square Park, only a block away from Downer’s house. The Central American boa his neighbor Joe Naegelen donated almost certainly did not (although in New York anything is possible). Here are a few examples of what was given:

Donated by Mr. H.M. Bedford of the United Fruit Company in 1913 and 1914.

Mr. Bedford worked at the shipping docks for the United Fruit Company in lower Manhattan. The Zoological Society corresponded with Bedford occasionally about shipping live animals to New York from Central and South America. It is likely that these animals were stowaways on one of the many fruit-laden ships that entered the New York harbor.

Donated by Mr. Thomas F. Freel, Superintendent of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, in 1913.

This is an interesting donation in that it came from an organization that was sometimes at odds with the Zoological Society. The SPCA wanted to sue the zoo in 1908 regarding their treatment of an elephant named Luna. Zoo visitors occasionally wrote to Hornaday threatening to report the zoo to the SPCA for what they interpreted as sub-par accommodations or inhumane treatment of animals. On the other hand, certain visitors saw the Bronx park as the arbiter of humane animal captivity and requested advice from Hornaday on the best-practices for captive animal care.

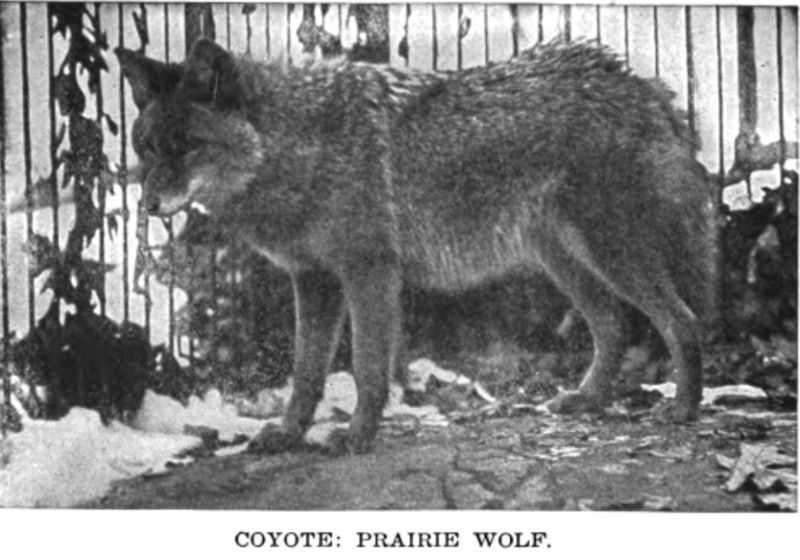

Donated by Miss F. Muth of 440 East 142nd Street in 1913.

Coyotes roam the five boroughs, even to this day. The archival record doesn’t explain how Muth came across this coyote, but it is possible that she captured the animal in her neighborhood in the South Bronx and tried to keep it as a pet.

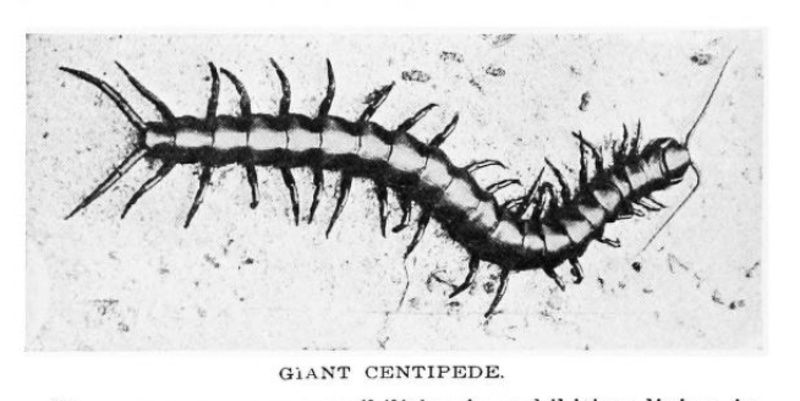

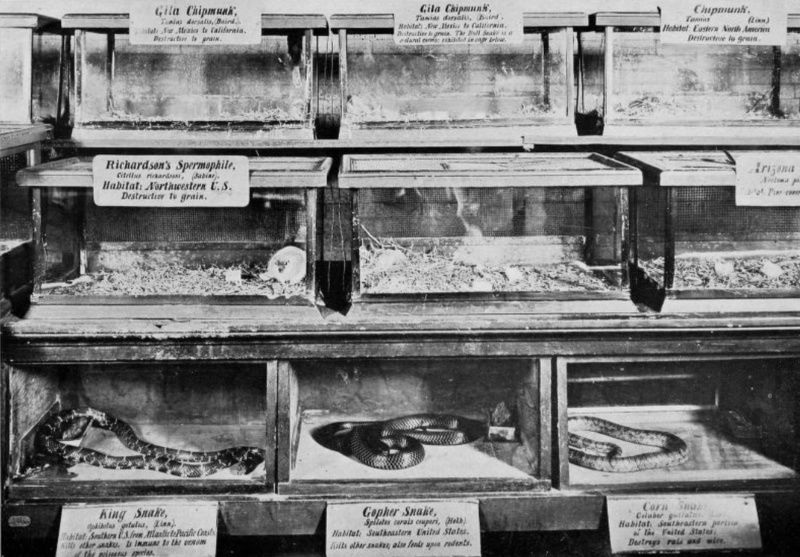

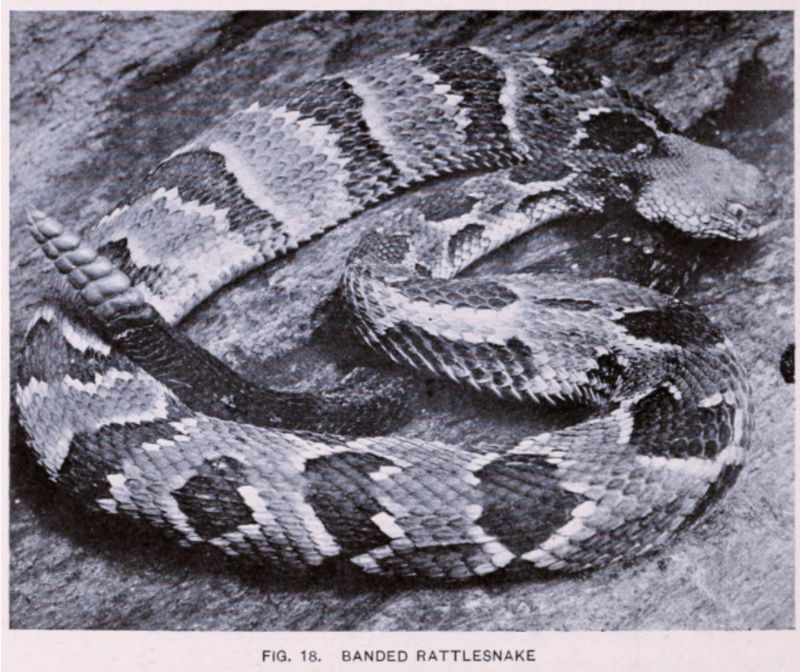

Raymond Lee Ditmars started as the Assistant Curator of Reptiles at the New York Zoological Park in 1899 and spent his entire career with the New York Zoological Society. He met his wife Clara in the Reptile House of the Bronx Zoo. Although he eventually became the Curator of Mammals at the park, he remained an avid reptile enthusiast and made frequent trips with his wife and two daughters to collect snakes around New York City.

In 1914 Ditmars donated: Three Rattlesnakes, one Black Snake, one Ring-Necked Snake, one Water Snake, one Pilot Black Snake, one Garter Snake, three Milk Snakes, one Storer’s Snake, one Green Snake, and one Greater Katydid.

In total, New Yorkers gave the zoo 785 living animals in 1913 and 1914. Most were small creatures, such as local snakes, young alligators purchased from pet stores, and songbirds, which were relatively easy to find and transport to the park. The large number of snakes donated might be due in part to the zoo’s willingness to accept them (they used them for new exhibits and as food for snake-eating snakes), and by some people’s enthusiasm for catching them, spurred on by Ditmars’ guide to New York City snakes. Head to the Gotham Center blog to see an interactive map that plots the addresses of all of the people who gave living gifts to the Bronx Zoo in 1913 and 1914.

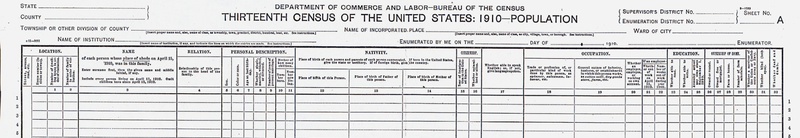

To understand more about who gave animals to the zoo, I turned to 1910 census data. Although imperfect, overlaying donor addresses onto census results about race and what the census called nativity (place of birth) gives an idea of how zoo donors were situated within immigrant and racial communities in New York City (for more on the context of the 1910 census see Paul Schor’s book Counting Americans). [4]

The 1910 census continued a line of questioning begun in 1850 that was designed to track the nation’s growing immigrant population. In addition to asking about a person’s “color or race” and the number of children they had, census enumerators recorded the place of birth of each respondent, as well as the place of birth of both of their parents. Census tabulators then used this information to figure a number of different statistics that looked at race, nativity, and reproduction together.

In the boroughs of Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island, there were not enough donors to make any correlations to census data. In the Bronx, proximity to the zoo spurred more donations than any affinities to 1910 demographic categories. But a pattern emerged in Manhattan — most donors were clustered in the Upper West Side, Midtown, and around Wall Street. These were the neighborhoods that, according to census tabulators, had the highest concentrations of people categorized as “native-born white of native-born parents” in the borough. In other words, people who gave animals to the zoo at this time lived in the areas of Manhattan that were densely populated by white people who had been in the United States for at least two generations (see Philip Deloria’s Playing Indian for more on the appropriation of “native-ness” and indigeneity by settlers in the U.S.).[5] Donors were notably sparse in areas with high densities of new and first-generation immigrant populations, such as the Lower East Side.

These findings are significant for two reasons. First, of the roughly 2,300,000 people who lived in Manhattan in 1910, only a small percentage of them were considered to be “native born white of native born parents” (15.8%, compared to 35.4% for New York State).[7] In a city composed primarily of immigrants and the children of immigrants, it’s notable that many zoo donors were likely to be otherwise.

Second, at this time Bronx Zoo administrators publicly promoted a white supremacist and nativist agenda. The New York Zoological Society was run by Henry Fairfield Osborn (president), Madison Grant (chairman of the executive committee), and William Hornaday (director of the zoo). Grant and Osborn were leading anthropological authorities of the time and are today considered to be the founding figures of the eugenics movement in the United States.[8] The three men wrote influential publications, including Grant’s now-notorious Passing of a Great Race (1916), that stoked fears of white racial decline and equated “non-Nordic” people with invasive pests.[9] Their books, pamphlets, and lectures promoted the idea that old-stock white communities had a special claim to land in the United States, and cast Indigenous and Black people, as well as new immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, as destructive poachers and poor stewards of increasingly imperiled wildlife. Through their involvement in the American Defense Society, Grant and Hornaday lobbied Congress to pass the Immigration Act of 1924 that instituted restrictive quotas based on national origins in ways that significantly limited non-European immigration to the United States.

While the role of the New York Zoological Society in shaping environmental conservation legislation is well known today, the institution’s involvement in the construction of racialized immigration laws is less so. It is my hope that tracing donors to the zoo will allow me to understand what kind of community the Zoological Society cultivated in the metropolitan area, and help piece together the historical connections between environmental conservation and immigration law in the United States.

A note about the 1910 census: Tabulations of statistics about New York State published by the Bureau of the Census were overwhelmingly focused on whiteness. Charts, maps, and explanatory texts repeatedly analyze ratios of foreign-born to U.S.-born white citizens and the origins of foreign-born white immigrants, while saying next to nothing about the more than 65,000 people in Manhattan and the Bronx categorized as “Negro” or “Other.” For this (and other glaring omissions), I use the 1910 census more as an indicator of white nativist anxiety, and tread cautiously when reading it as a historical source about the people of New York City in the early 20th century.

This research is in its beginning stages. I share it with you now in part to experiment with digital mapping as a method for historical questioning. When archival access returns, I plan to expand the map to include donors from beyond New York City and incorporate information about the relative abundance or scarcity of historic animal populations.

Katherine McLeod is a PhD candidate at New York University. Her dissertation situates the New York Zoological Society within a global network of empire and economics in order to investigate the trans-imperial dimensions of animal collection, ecology, and zoological display in the early 20th century.

Next, check out 15 Famous Animals of NYC

Sources

[1] Zoological Park Opened E.W. Scott, “Zoological Park Opened.” New York Times. November 9, 1899.

[2] In thinking through questions of race, indigeneity, empire, and animals (not necessarily together), I am indebted to the scholarship of Lisa Uddin, Christina Sharpe, Noenoe K. Silva, Dean Saranillio, Tracy McDonald, Donna Haraway, Jodi Byrd, Lisa Lowe, Juno Parreñas, Paige West, Karen & Barbara Fields, Gabriel Rosenberg, and Gayatri Bahadur.

[3] Animal Origins Map – Donor names & addresses: Directors Office Outgoing Corresp, Dec. 1912-March 1915. William T. Hornaday and W. Reid Blair outgoing correspondence, 1895-1939. Collection 1012. Wildlife Conservation Society Archives, New York. Head to the Gotham Center blog to interact with this map!

[4] Paul Schor, Counting Americans: How the US Census Classified the Nation (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Pres, 2017).

[5] Phillip Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999).

[6] Census Data Census Literature: Division, US Census Bureau Administration and Customer Services. “US Census Bureau Publications – Census of Population and Housing.” Accessed August 28, 2020. Individual census responses: ancestrylibrary.com; Aggregate data sets: Steven Manson, Jonathan Schroeder, David Van Riper, and Steven Ruggles. IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 14.0 [Database]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. 2019

[7] Statistics for New York City, 1910 Statistics for New York, Dept. of Commerce and Labor Bureau of the Census. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office (1910), 593.

[8] Kohlman, Michael. “The Anthropology of Eugenics in America: Ethnographic, Race-Hygiene and Human Geography Solutions to the Great Crises of Progressive America.” Alberta Science Education Journal 42, no. 2 (July 2012): 32–53.; See also: Stern, Alexandra. Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America. Berkeley, CA: University of California, 2015.

[9] William T. Hornaday, Our Vanishing Wild Life: Its Extermination and Preservation (New York: New York Zoological Society, 1913).; Madison Grant, The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916).; Henry Fairfield Osborn, Men of the Old Stone Age: Their Environment, Life and Art (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1915).

Subscribe to our newsletter