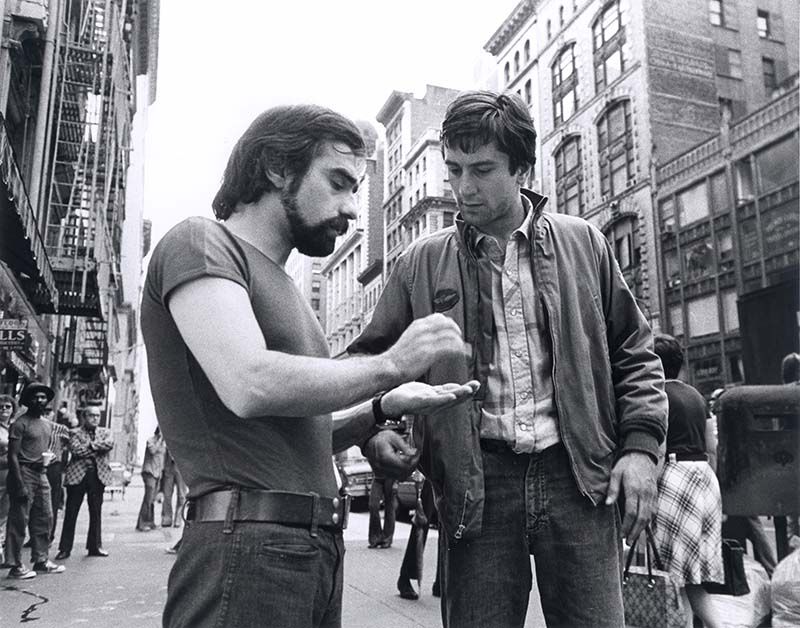

Martin Scorsese’s films are classics. Taxi Driver. Goodfellas. Gangs of New York. Yet as much as these films are tied to this director, they are also bound up in their New York City settings. Directors like Scorsese help us make sense out of a vast, diverse, complicated landscape, and in turn this landscape enables this director to explore what it means to be American and what it means to be a man. Yet in his particular way, Scorsese’s exploration of New York City and humanity is one that makes the city and its characters feel both familiar and strange, both known and unknown, both knowable and unknowable.

Entry area and title sign. Photo: Thanassi Karageorgiou/Museum of the Moving Image.

“Martin Scorsese” is a retrospective produced by the Deutsche Kinemathek in Berlin and on display at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, Queens. While the exhibit has signature artifacts like storyboards from Raging Bull, costumes from Gangs of New York, and Polaroids from location scouting for Taxi Driver, its most innovative installation is a display that maps cinematic sites onto the real city, offering a Manhattan grid that is articulated by movie screens tying signature scenes to real life intersections. It is this display that combines time and space in a way that is impossible on a DVD or even on a city street. It is this display that is unique to the museum. It is this display that gives us new insight into Scorsese and into the city.

As the exhibit argues, there are numerous thematic avenues into the work of Martin Scorcese. The American Family. Italian-American identity. Religion. Gender. History. But because museums should never be understood outside of their own geography, what MoMI adds to the discussion of Scorsese’s films is a location in New York City and in Queens. It highlights both Scorsese’s biography as a son of Corona and Little Italy, and it highlights the museum’s own occupation of the site of the historic Kaufman Astoria Studios. If there is nostalgia in Scorsese’s films and in Scorsese himself for ethnic enclaves like Little Italy the way it used to be, might we not find those here still in Queens as much as anywhere else?

A wall of marketing images relating to New York City-set movies directed by Martin Scorsese, with props and a costume from Gangs of New York (2002) inset in alcoves. Photo: Thanassi Karageorgiou/Museum of the Moving Image.

And like Queens as a place that juxtaposes the sense of time and sense of place of dozens if not hundreds of communities, ethnicities, religions, and nationalities, Scorsese’s films and “Martin Scorsese” the exhibit play with time inside this framework of place and New York City. Here are mixed eras from the 1862 of Gangs of New York to the Gilded Age of The Age of Innocence, from the Vietnam War era of Taxi Driver to the post-World War II days of the Mafia in Goodfellas.

Building on the confusion of time that marks Scorsese’s histories of New York is the confusion of time that marks the visitor’s own viewing of the exhibit and those films. Like songs or photographs, films are catalysts of memory. Where did we first see Taxi Driver? Who first introduced us to Goodfellas?

Movie posters from Martin Scorsese’s personal collection, including “I Vitelloni,” “The Red Shoes,” and “The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp,” appear in the “Cinephile” section of the exhibition. Photo: Thanassi Karageorgiou/Museum of the Moving Image.

The challenge of the film exhibit is that the answers to these questions are so unstable. Nearly everyone who has seen “Starry Night” has seen it on the white walls of the Museum of Modern Art, and each time it is displayed it is displayed in its entirety. Likewise, if you have seen the Declaration of Independence, you have seen it at the National Archives and every time you see it you see all of it. But films? A drive-in movie experience in the 1970s is different from a 35mm print at a film festival is different from a rebroadcast on cable is different from a digitized clip shown in a retrospective at a museum. We bring so much more to these images than we do to a Van Gogh or a Monet or a set of dinosaur bones. We remember these films as they were and as they are, we remember New York as it was in the 1860s, the 1970s, and now. Using this, the Museum of the Moving Image and “Martin Scorsese” play with representation and its relationship to time and memory as much as its relationship to space.

In the foreground, a costume designed by Sandy Powell and worn by Cate Blanchett as Katharine Hepburn in The Aviator (2004). Photo: Thanassi Karageorgiou/Museum of the Moving Image.

The Museum of the Moving Image is dedicated to the question of what a museum of film and television looks like. In its permanent exhibit, it uses cameras, projectors, and television sets to explore the technology of the moving image. It uses costumes, prosthetics, and props to reveal the labor behind movie magic as it appears on screen. It uses interactives to put visitors at the animator’s table, in the editor’s chair, or at the arcade, as well as in front of the film screen and the television set. It has long used the tradition of the museum and the artifact as a complement to the more conventional cinematic practice of simply screening films as evidence or documents of art and history.

The Scorsese family dining room table and chairs. Photo: Thanassi Karageorgiou/Museum of the Moving Image.

Into this way of thinking about film and the museum comes “Martin Scorsese.” In the tradition of the art gallery retrospective, “Scorsese” is an exploration of the career of a single artist. It offers biographical information in order to connect the subjects of Scorsese’s films to the world in which the author lived and worked. It shows working storyboards, scripts, and memos that reveal how the director’s most famous films were conceived, not unlike a museum exhibit’s display of preparatory drawings. And it highlights themes that define Scorsese as an auteur across his films, themes like gender and family, Catholicism and religion, violence and the Mafia, Italian-American identity, and—importantly—New York itself. In other words, much like the tradition of film criticism, “Martin Scorsese” uses the conventions of art history to legitimate a more recent form of popular culture simultaneously through art, history, and even science. The exhibit, and especially its representation of New York City, is an exercise in crossing disciplinary and institutional boundaries as well as in crossing boundaries of time and space.

A view of the video installation (13 mins) created by curator Nils Warnecke, in the Museum’s video screening amphitheater (on screen: scene from The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). Photo: Thanassi Karageorgiou/Museum of the Moving Image.

However, while there is plenty to like about “Martin Scorsese,” it can be a little uneven as it comes to its interpretation of the artifacts on display. Indeed though the exhibit’s crossing of disciplinary boundaries is innovative, it sometimes relies too heavily on the art curator’s assumption that the artifact or the film can speak for itself, not turning heavily enough to the historian’s emphasis on explanation and interpretation. Like the museum’s permanent exhibit, the mission here is often to demystify movie magic. While revealing the labor that goes into producing a film serves a vital educational purpose, there is not enough discussion here of the choices Scorsese and his staff make or, perhaps more importantly, fail to make. Which New York is on display in these films and in this exhibit, and which isn’t?

Photo: Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro on the set of TAXI DRIVER (1976). Image courtesy of Sikelia Productions.

What’s more, even the themes which it does offer up for interpretation are painted in strokes that are sometimes too broad and are not critical enough. Scorsese is a perfect opportunity to scrutinize film with the eye of a historian or a geographer while drawing in the audiences which are attracted to both art exhibits and pop culture. As much as there is to like about Scorsese’s New York and MoMI’s New York, there is still room for it, or something like it, to be better.

The “Martin Scorsese” exhibition is on view at the Museum of the Moving Image, Dec. 11, 2016–Apr. 23, 2017.