Last Chance: The Annual Orchid Show Soars at the New York Botanical Garden

The vibrant colors of Mexico come to NYC for a unique Orchid Show at NYBG!

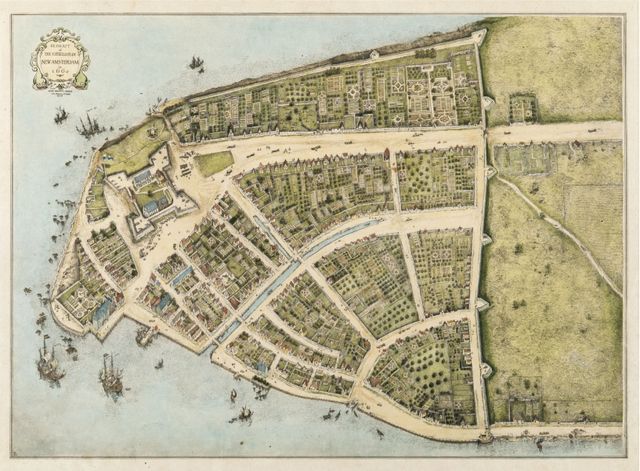

A redrawn version of the 1664 Castello map of New Amsterdam. Image via Wikimedia Commons

In his book, The Island at the Center of the World, author Russell Shorto argues that New York City’s open, tolerant and multicultural society is directly linked to its origins as the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. The mix of men with different languages, colors and practices in the mother country as well as their far flung colonies was deemed by the Dutch to be good for trade. Shorto labels this open-mindedness a “state policy of tolerance” – with one notable exception. Homosexuality was a crime throughout the Dutch empire. The punishment was death.

In 1632, the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam (which we’re hosting a tour about) was centered on trade with the Indians for beaver pelts. Enter Harmen Myndersz van den Bogaert, a Dutchman, age 18. Listed as a barber-surgeon in the ship manifest of the Unity, Harmen’s list of essential skills for the New World city included trimming beards and shaving. Other skills with razors and blades were bloodletting and amputations – a link with Peter Stuyvesant who would be the instrument of Harmen’s demise.

Tour of The Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam

Harmen’s New Amsterdam was a fortified city confined to the southern tip of Manhattan island. Much of its business was conducted up the Hudson River at the trading post of Fort Orange and the city of Rennselaerwyk, established where the Mohawk and Hudson Rivers met (later Albany). But Harmen’s life in the New World ran well beyond the physical and social confines of the Dutch colony.

The southern tip of Manhattan with Fort Amsterdam in 1626. Dutch ships arriving from Europe and Indian canoes with beaver pelts mingle in the harbor. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Shorto describes van den Bogaert as a man of action with many interests unique to the New World. In addition to his bouwerie or farm on Manhattan, he had an interest in a privateer, La Garce, that raided English ships in the Caribbean. He served as supply master to the Dutch West India Company in New Amsterdam, and later at Fort Orange. In short, he was an intrepid New World colonist with varied enterprises and interests. Among those interests, was a fondness for men; specifically his slave, Tobias. The Dutch settlement on Manhattan received slaves from Africa as part of the cargo brought by Dutch merchant ships to the new colony.

A depiction of the city of New Amsterdam circa 1642 with slaves unloading cargo from ships. Image via Wikimedia Commons

In the autumn of 1634, Harmen, was found in flagrante delicto with Tobias. In a bid to escape certain punishment, Harmen and Tobias hit the road. Or, they would have, if one had existed. Instead, they fled to where there were no roads, no jails and no European laws against homosexuality. Indeed, there seems to have existed among the Native Americans an acceptance of homosexuality. Harmen and Tobias fled to Mohawk country, crossing untamed woodland in a bid for freedom.

The flight into the wilderness was their only chance for escape – and they might have had a shot at freedom. The woodlands and its inhabitants were known to Harmen. In the winter of 1634, he had been part of a Dutch mission negotiating with the Mohawk Indians for beaver pelts. It was a sensitive diplomatic mission in which the Dutch had to contend with competing French interests in the fur trade. The goal was to convince the Indians that the Dutch were better trading partners. It had worked.

Harmen van den Bogaert’s 1634 journal of that winter mission has been preserved, and a translated by Charles Gehring of the New Netherland Institute, and is available today in print or as a Kindle edition. Gehring’s translation was the inspiration for author/illustrator George O’Connor, who wrote a 140-page graphic novel based on Harmen van den Bogaert’s journey into Mohawk territory.

Van den Bogaert describes Mohawk villages and their longhouses covered with elm bark inside picketed palisades. His journal relates how he and his companions were welcomed to one longhouse and given baked pumpkin, beans and venison. What else transpired, we can only guess. Shorto describes the journal as containing “a detailed list of Mohawk vocabulary words Harmen compiled.” These include “man,” “woman,” “prostitute,” “vagina,” “phallus,” “testicles,” “to have intercourse” and “very beautiful.” In a creepily prescient action, van den Bogaert also recorded the Mohawk phrases “When shall you return?” and “I do not know.”

Now, van den Bogaert was returning to the Mohawk village as a hunted fugitive. Preceding Dog the Bounty Hunter by almost four hundred years, a woodsman named Hans Vos was dispatched to bring van den Bogaert and Tobias back to New Amsterdam to face Dutch justice. Vos cornered the fleeing men in a Mohawk longhouse. A shootout ensued and a fire, possibly set as a diversion, burned the longhouse and its contents. Van den Bogaert and Tobias were captured and brought back to the prison in Fort Orange.

A letter was sent to Peter Stuyvesant, the director-general of the West India Company who directed company business and dispensed justice in New Amsterdam. Stuyvesant had only set foot in Manhattan earlier that year– – more correctly, one foot and one wooden peg. He had vowed to act “like a father over his children” in his rule of the colony, though his own father was a strict Calvinist minister who viewed homosexuality as a sin.

A map showing Manhattan and Rensselaerwick linked by the Hudson River and perfectly situated for trade in beaver pelts in the Native Americans. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Stuyvesant’s reply was that he would stand in judgment of van den Bogaert at Fort Orange in the spring. Presumably he meant to make the journey from New Amsterdam via the company sloop when winter ice no longer froze the northern portions of the Hudson. Certain that the director-general would impose the death penalty, van den Bogaert and Tobias broke free from the Fort Orange prison, fleeing across the frozen Hudson River. Where today, the I-90 crosses the Hudson River, van den Bogaert fell through a hole in the ice and drowned. Tobias was recaptured. Van den Bogaert thus achieved the dubious distinction of the first death in the Dutch colony due to sexual preference. (There were more to come.) Tobias’ fate is unknown.

After his death, the Mohawks sent a delegation to the Dutch West India Company. The Indians demanded the Dutch make good on the loss of their longhouse and its supply of grain that had been lost to van den Bogaert’s arson. Hopefully, this puts to rest the idea that the Indians had been duped into selling the Dutch the entire island of Manhattan for 24 dollars. They had a good grasp on the Dutch legal system and Stuyvesant ruled in their favor.

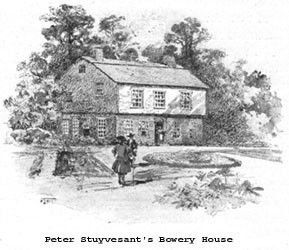

Van den Bogaert’s Manhattan property, a bouwerie at about 47 Street and Second Avenue, was sold. The money was used to pay the company’s debt to the Mohawks. As for Stuyvesant, we all know the story of the 1664 British take over of New Amsterdam and its rechristening as New York. Instead of returning in disgrace to Holland, Stuyvewant lived out his life on the island of Manhattan that came under British rule. He established a bouwerie in what is today, Greenwich Village, the spot where gay rights were born at the Stonewall Inn.

Peter Stuyvesant’s bowery house. He died here at the age of 60 in 1672, after surrendering New Amsterdam to the English in 1664. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

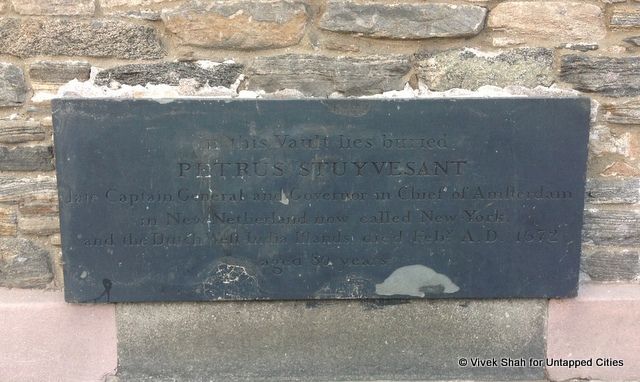

In death, Stuyvesant is locked for eternity with the birth of gay rights. He is buried in Greenwich Village at St. Marks-in-the-Bowery Church. His epitaph, embedded in the foundation of the church, gets both his age and title (director-general, age 60) wrong. His restless ghost has allegedly been spotted numerous times over the years and is said to walk, thumping its wooden stump, on the floorboards of the church at night.

St. Marks-in-the-Bowery in the East Village houses New York City’s oldest continuously used house of worship. It is rumored to be haunted by the ghost of Peter Stuyvesant.

Tour of The Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam

Next, join us for our upcoming tour of the remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam, read about the Top Ten Secrets of New York City’s Former Slave Market and The History of NYC Streets: Stuyvesant Street. Get in touch with the author @KimDramer.

Subscribe to our newsletter