A Salvaged Banksy Mural is Now on View in NYC

This unique Banksy mural goes up for auction on May 21st in NYC!

When Michael Bloomberg was elected mayor of New York in 2001, no one predicted he would become a revolutionary, reshaping the city’s physical landscape, economy, and cultural character. Yet in 12 years he rezoned 40 percent of the city’s land, opened up much of its waterfront to development, created thousands of acres of new parkland, brought crime down to unmatched low levels, supported cultural institutions on an unprecedented scale, redesigned streets and public spaces to host bike lanes and pedestrian plazas, and stamped the city with his personal influence in a way that no other mayor ever has.

Recognizing that New York may be facing momentous change as it says farewell to Bloomberg and elects its new mayor in the fall, the Forum of Urban Design—an eminent group of architects, planners, developers, civic leaders, and academics—held a series of breakfasts this spring to pitch and discuss bold proposals for what it called a “more competitive, livable, and sustainable New York.”

Editing the most compelling ideas into 40 proposals, the Forum published “Next New York: A Sketchbook for the Future of the City” this week, releasing it at a dinner that began with a conversation between two former deputy mayors—John Zuccotti from Mayor Abraham Beame’s administration in the 1970s and Daniel Doctoroff from Bloomberg’s. Zuccotti and Doctoroff have in common that they were both appointed when New York was thought by many to be on the edge of the precipice—from which it might have plummeted to disaster or, as it has done repeatedly, emerge triumphant. We see the successful results today.

Daniel Doctoroff, Julia Vitullo-Martin and John Zucotti at this week’s event for Next New York

I chaired the conversation, as we discussed their assessment of the Forum’s proposals, and their own strong views of which were practical, inspired, and worthy of investment. Doctoroff, now CEO and President of Bloomberg LP, argued for the “virtuous cycle of the successful city,” meaning that growth is good because the marginal revenue from each additional person tends to be greater than the marginal cost, the profit by which the city can reinvest in the quality of life. “We want our city to be a compassionate city,” he said. “We pride ourselves on that. But at the end of the day, if you don’t make money, you can’t create the right kind of city with the kind of values we want.” How are you going to generate the revenues, he asked, to keep the virtuous cycle working?

Zuccotti, now co-chair of Brookfield Office Properties, who served as deputy mayor during the dark days of New York’s fiscal crisis, cast a gimlet eye on many governmental financial arrangements, emphasizing that crucial projects often fail to get the “substantial resources that are available.” Calling this “the institutionalization of misplaced resources,” he cited the Second Avenue Subway as an example of an originally overly ambitious–but now stripped-down–project depriving more important projects (the Train to the Plane or public transit in the outer boroughs) of money. Why are we building this little strip of a subway? he asked–a mere stubway. It offers no added value. Doctoroff called SAS “a silly little spur that doesn’t generate anything other than some convenience for people who are perfectly happy to live where they live without it.”

These comments went viral, with transit advocates objecting vehemently. Yet as Forum member John Alschuler, chairman of HR&A, points out, “The Second Avenue Subway is far down on the list of the parts of our city that could be most transformed by transit. The most important aim is to democratize access to employment, spreading access of jobs as much as possible and expanding the supply of land that can be redeveloped for housing.”

But Next New York has put a number of projects on the table that offer added value, in effect, democratizing access to employment and potentially transforming New York. Here are a few of them.

New York has never been a light-rail kind of town—“toy trains,” said a Koch deputy mayor dismissively in the 80s. Yet the time has surely come. Forum President Alexander Garvin proposes situating a light rail line along 21st Street in Astoria, which he points out is the widest thoroughfare before reaching Vernon Boulevard. A first phase would connect Astoria and Queens Plaza; a second would extend across Newtown Creek and along the Brooklyn waterfront to Red Hook.

This is the book’s single best idea, said Doctoroff. It would knit together the emerging communities along the 7 and L lines, and would trigger all sorts of incremental growth on the Brooklyn-Queens waterfront, where the greatest potential for growth actually is. What’s more, light rail is cheap—some $20 million, he guesses.

Zuccotti agreed about light rail, and emphasized that new transportation projects should be in Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx, because that’s where housing can be built at reasonable cost in areas that are still zoned industrial. He cited the brilliant precedent of David Walentas, who showed definitively in Dumbo, Brooklyn, how to convert empty industrial space into a thriving mixed-used community. Can the same be done in the Bronx and Queens?

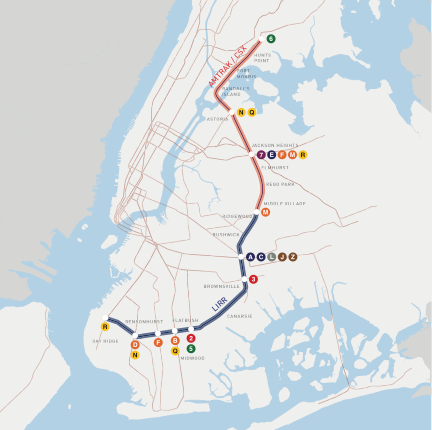

Recognizing the newly found economic importance of the outer boroughs, Regional Plan Association President Robert Yaro resurrects an idea from RPA’s Third Regional Plan—the New York Triboro Overground, a regional express rail that looks on the map rather like a glorified G line, running from Hunts Point down through Astoria, carving inward through Emhurst, Bushwick, Brownsville, and Flatbush, terminating in Bay Ridge. It would build on the many unused or under-used rail lines that now cross through the outer boroughs, and would connect with every major subway line except those running exclusively in Manhattan.

Doctoroff is skeptical because he doesn’t think the neighborhoods to be served by the Overground are really emerging. An architect in the audience, however, notes that nearly all of his firm’s 50 or so young employees live in the neighborhoods along and beyond the Overground. This is really an empirical question that the Department of City Planning could answer: where are newcomers finding housing now, and where are they likely to live and work in the future? Equally important, would the Overground stimulate the renovation and expansion of adjacent neighborhoods, attracting the investment some of them desperately need? The Overground could actually test–and vindicate–Doctoroff’s cycle of virtue.

Transportation scholar Peter Derrick says we need one regional rail system, creating a true system out of the independent lines—Metro North, Long Island Rail Road, and New Jersey Transit—that now exist. This means, for example, allowing through-running at Penn Station to permit New Jersey trains to travel through the city to Long Island and northern suburbs. Imagine, he notes, if riders could travel from Co-Op City in the Bronx to Meadowlands Stadium, or from Princeton to New Haven.

Zuccotti like this but points out it would require an awful lot of cooperation that has historically not been forthcoming—from governors, federal officials, even the White House. Yet it puts us all in a friendly sort of mood towards New Jersey, and therefore ready for the next important proposal.

The President of Related Hudson Yards, Jay Cross, wants to extend the 7 line to Secaucus (later in the book architect Clare Weisz suggests pushing it all the way to Pittsburgh!), bringing the subway to New Jersey, and maximizing what Cross calls the Popular Culture Corridor. (The 7 links the stadiums in Flushing with the arts communities of Long Island City, the theaters of 42nd Street, and Hudson Yards, the 26-acre site to be developed by Related).

Creatively financing the 7, which was one of Doctoroff’s early achievements, could continue beyond Manhattan’s borders, but would inevitably become involved with “institutional and legislative messes” in other jurisdictions. Still, if Hudson Yards develops as successfully as Cross projects, it may help modify the border wars that stymied other Hudson crossings. Doctoroff is chairman of the board of Culture Shed, a spectacular 170,000-square-foot visual and performing arts center to be designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro and Rockwell Group. When built at the southern end of Hudson Yards, it will be a game changer both for the West Side and its neighbor across the river.

From a global city point of view, the most transformative transportation service is that of the region’s airports–the first thing most visitors, whether business or tourist, see when they come to New York. In a study of the nation’s 20 busiest airports released this week, the Global Gateway Alliance rated LaGuardia dead last and Newark second to the last on amenities expected in 21st-century airports. But while there’s no question that the region’s airports can offer a truly dreadful experience, getting to or from them can be even worse.

Grimshaw Architects proposes to create express connections between the airports and the city’s major transportation hubs–Grand Central Terminal, Penn Station, and the World Trade Center Transportation Hub–by leveragaing existing infrastructure to create high-speed connections of under 30 minutes. This is an ancient dream, of course, and one actually being implemented by London. The Grimshaw proposal would be immensely expensive, but there’s an interim step.

A new rail connection could run express, writes Alex Garvin, from the tunnels under either Penn Station or Grand Central via the new East Side Access Tunnels, through Sunnyside Yards toward Hell-Gate Bridge along the same right-of-way. The city would only have to acquire one private lot to accomplish this. Doctoroff agrees this is a great idea–and that using the existing rail lines already owned by the MTA or Amtrak–would be brilliantly efficient. But, he says, the campaign would have to be led by the governor, whose agencies control most of the route.

In his introduction before dinner, Alex Garvin described the proposals as ranging from pragmatic to fantastical. New York is something of a fantastical city–8.5 million people living in energetic density on four island-boroughs plus one attached to the mainland. Proposals that seemed unlikely 20 years ago are now being implemented. Mary Anne Gilmartin, for example, exhorts: “embrace modular construction,” long disdained for serious buildings in New York. Her company, Forest City Ratner, is building the world’s largest residential modular tower at Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn. Doctoroff applauds modular’s ability to bring down construction costs, something he regards as essential for New York’s future.

Developer Donald Capoccia of BFC Partners wants to train unemployed and underemployed New Yorkers as construction workers, especially in the transitioning neighborhoods where the majority of affordable housing is being built. He has already shown it can be done at the Toren, where he hired residents of nearby public housing. West Side developer Robert Quinlan would entice talented newcomers by offering them truly affordable housing–micro apartments to be built in outer borough manufacturing areas adjacent to emerging residential neighborhoods. He would rezone Bushwick, Gowanus, Red Hook, Long Island City–neighborhoods that he says already have studios, sound stages, and nightlife. The rezoning should not mandate costly residential amenities. They won’t be necessary because the new young residents will be outside, animating the streets.

Next New York has thrown down a gauntlet for the next mayor–40 ideas to be debated and pushed. And why not? As Doctoroff said, New York is an aspirational city, a place where people come to do great things and where great things get accomplished.

Stay tuned for our in-depth column on the subjects covered by the Next New York breakfast series. Julia Vitullo-Martin is a Senior Fellow at Regional Plan Association and director of the Center for Urban Innovation. Get in touch with her @JuliaManhattan.

Subscribe to our newsletter