Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

This is part of an ongoing series on ideas from Next New York, a project by the Forum for Urban Design.

Serial entrepreneur Elon Musk isn’t the only one dreaming up outlandish new transportation modes with the Hyperloop. Over the past four months, the Forum for Urban Design invited architects, planners, developers, engineers and academics to brainstorm ways to fundamentally update New York’s housing, parks, schools and transportation for a new century. Through a series of roundtable discussions attended by Untapped Cities culminating in a dinner party with some of the city’s most powerful and creative minds, the Forum gathered 40 proposals that it will publish in a book due out this month called “Next New York.”

Not surprisingly, the city’s roads, tracks, and tarmacs drew some of the most, ahem, imaginative proposals—and impassioned discussion. Here is a roundup of our favorites.

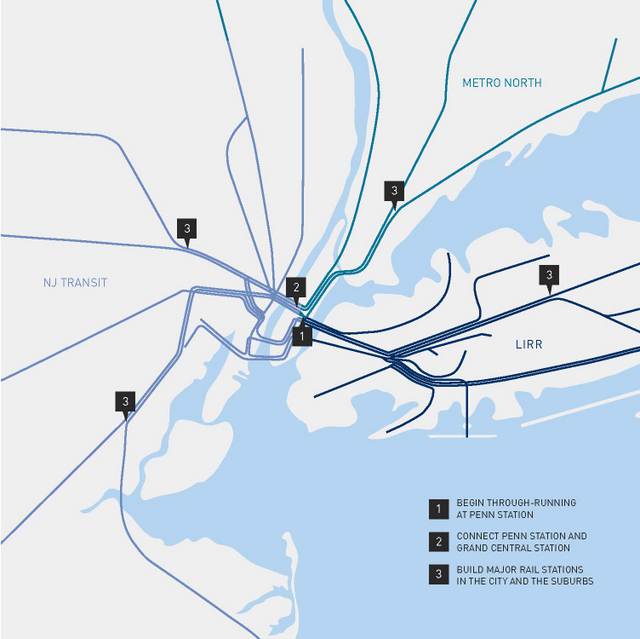

Robert Yaro, president of the Regional Plan Association, likes to point out that until 1989 there were two world cities with divided transportation systems: New York and Berlin. “Berlin fixed their problems but we still haven’t fixed ours,” he laments. All three commuter rail systems—Metro North, Long Island Rail Road, and New Jersey Transit—operate as separate entities. The MTA’s East Side Access project aims to relieve congestion at Penn Station by rerouting some Long Island trains to Grand Central Terminal. But that does nothing to address the fact that virtually every cross-regional rail trip involves a transfer in Manhattan. On top of that, connecting between the two Manhattan train stations requires at least one additional subway transfer.

So Peter Derrick of NYU’s Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management proposes “through-running” at Penn Station to allow New Jersey trains to travel through the city to Long Island and the northern suburbs. Meanwhile, Jay Cross of the Related Companies has resurrected an old Bloomberg plot to extend the 7 subway line from its future West Side terminus across the river to Secaucus, New Jersey. Of course Related has a self-serving stake in that idea: its massive Hudson Yards development sits at intersection of what Cross calls the “High Culture Corridor” (the Whitney’s new Meatpacking home, the High Line, the future Culture Shed) and the “Popular Culture Corridor” (Citi Field, Long Island City, Times Square). Why not tack on MetLife Stadium?

The G train just can’t catch a break. The only subway line without a stop in Manhattan has been blamed for everything from confounding tourists to straining relationships. Through two parallel but not necessarily competing projects, Robert Yaro and Forum president Alexander Garvin want to relieve some of the pressure on the much-maligned G by offering more options for the increasing numbers of Manhattan-averse commuters. The New York Triborough Overground would be a regional express rail arcing from Hunts Point in the Bronx through Queens to Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, and connecting to almost every subway line along the way. Yaro points out the entire route could utilize existing rail beds currently owned by Amtrak, LIRR or CSX, a freight rail service. Garvin proposes a light rail line that would connect Astoria with Red Hook along 21st Street in Queens, across Newtown Creek, and along Brooklyn’s waterfront.

One thing every New Yorker can agree on is the Dantean inefficiency of the city’s transit connections to the three major airports. Andrew Whalley and Gregory Haley of Grimshaw Architects make the obvious but depressingly unlikely suggestion of connecting each airport with direct express rail service to Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal. But Garvin offers this glimmer of hope: connecting LaGuardia to Grand Central would require the acquisition of just one lot of private property – the rest could be routed along existing Amtrak and LIRR railways and in the medians of existing highways.

Like human skin, which doesn’t get enough credit for being the largest organ of the body, Claire Weisz of WXY Architecture + Urban Design complains that “not enough people understand that streets compose the largest percentage of New York City available to the public.” Despite the fact that a minority of New Yorkers own cars, any attempt to reduce the amount of the city’s real estate dedicated to them invariably incites a wide and loud uproar.

But Weisz and partners Mark Yoes and Jacob Dugopolski are undeterred. Their plan for “supercharged transit corridors” consists of car-free streets with linear parks, protected bike lanes and mass transit. Long-range bike corridors would be paired with a surface mass transit line like light rail or bus rapid transit with boarding platforms located in the center median of major two-way boulevards, sheltered from the elements and level with bus doors for faster boarding. Wide, car-centric streets like Queens Boulevard would make the perfect candidates for a redesign like this, suggests Streetsblog editor Ben Fried. Auto traffic would be limited to taxis, carpools, and electric vehicles, or banned altogether on certain streets. Meanwhile, planted buffers could protect bike lanes while capturing rainwater, relieving the sewer system, and reducing the heat island effect.

Paul Steely White of Transportation Alternatives goes a step further and proposes grade-separated bike superhighways – wide, continuous protected bike lanes with prioritized, unbroken rights-of-way. His model is Copenhagen, where bike superhighways are supported by stoplights that are timed with cycling speeds (12-13 mph) to reduce some of the primary obstacles to urban cycling: frequent stopping, unsafe intersections, and circuitous routing.

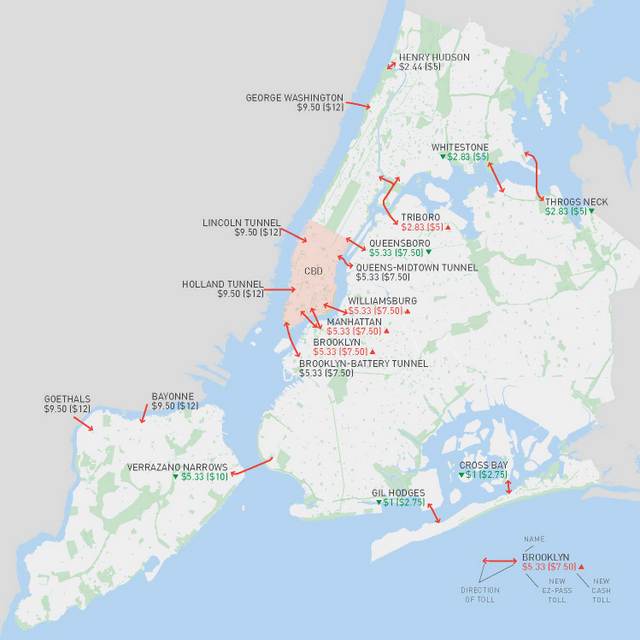

Sam Schwartz has an even more divisive idea: return tolls to the East River bridges and charge all autos driving south of 60th Street in Manhattan. Establishing a pay wall around Manhattan below Central Park isn’t a new idea – Bloomberg made a failed attempt to institute so-called congestion pricing back in 2008, citing successful examples in London and Singapore. But Schwartz goes deeper. He argues the pricing on the city’s bridges is arbitrary, based on whether MTA or DOT runs the crossing. Drivers on the perma-congested Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges get a free ride while those on the far-flung Whitestone and Throgs Neck bridges fork over $7.50. If drivers were to pay proportionately for the cost they inflict on the city’s traffic, Schwartz estimates $1.5 billion in new revenue would be generated annually, which could be directed toward transit maintenance and highway and transit capital improvements.

High Line fever has reached such epidemic scale that it is now coming back full-circle to the city that birthed it. And no, we’re not talking about the Lowline. Landscape architect Laurie Beckelman is reviving an on-again, off-again call to park-ify a section of an elevated railway in Queens. The Queensway, as it is known, is a 3.5-mile stretch of abandoned LIRR track stretching from Rego Park to Ozone Park. Beckelman estimates the park would serve a population of 140,000 residents within a ten-minute walking radius, and imagines activities including concerts, public art, multi-ethnic food festivals, yoga, even cycling, which is banned on the High Line. Meanwhile, Susannah Drake of dlandstudio wants to put a park over a below-grade portion of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway in Williamsburg. She thinks the projected increase in property values in the surrounding area could pay for up to 75% of the park’s initial cost. Beckelman is less bullish on eastern Queens – she admits fundraising may be a challenge given the Queensway “does not share the same sexiness” as its older sister in Manhattan.

What keeps University of Pennsylvania architecture professor Marilyn Jordan Taylor up at night? “I truly honestly worry that the 500,000 people who plod through Penn Station everyday have given up hope that it’s ever going to be any different,” she confessed to a crowd of transportation nerds last March. Those 500,000 commuters represent more than triple the daily traffic at JFK, on a footprint roughly 1/160 the size. And that number is only expected to rise. Taylor proposes expanding the tracks and platforms southward to increase capacity by 50%, replacing the “miserable basements with a grand civic gateway full of light and services,” and lining surrounding streets with cafes, shops and wide, welcoming sidewalks. Taylor does not shy away from politically-tinged demands like building more tunnels to New Jersey or moving Madison Square Garden. A new Penn Station with high speed rail links is necessary to maintain New York City’s global economic competitiveness, she argues, and “catalyze the redevelopment of its sad surroundings.”

Stay tuned for the next installment of Next New York. All images courtesy of the Forum for Urban Design

Subscribe to our newsletter