Photograph by David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Photograph by David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

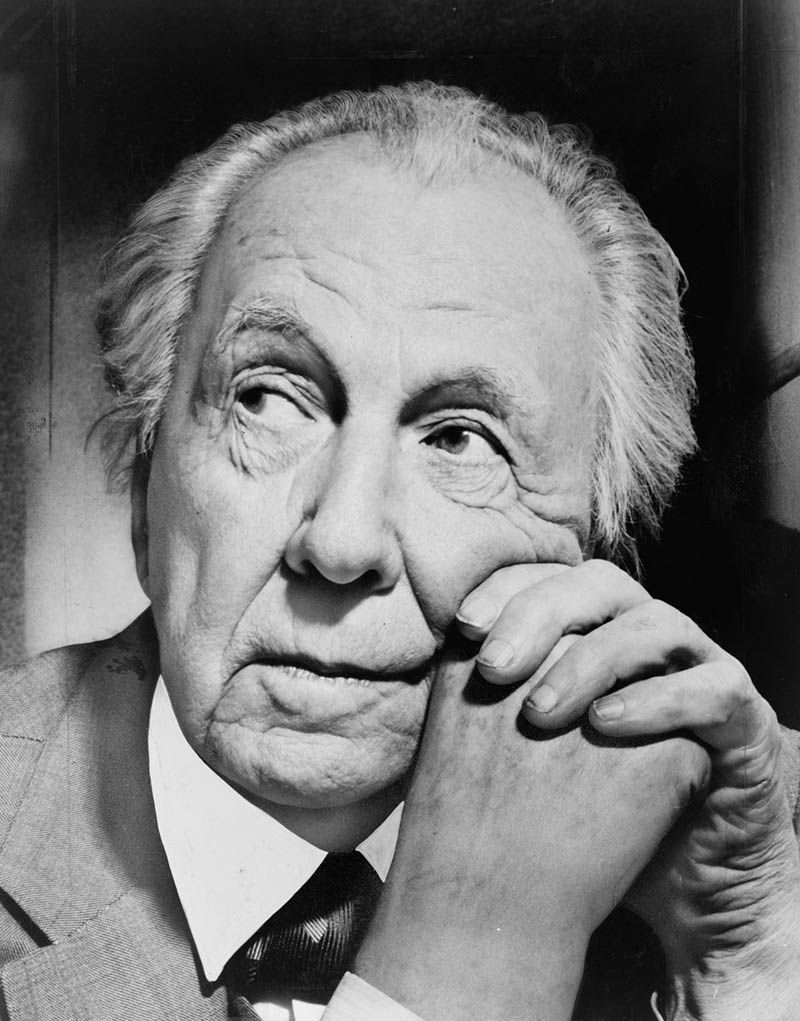

Few buildings in New York City strike a more iconic silhouette than the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in the Upper East Side of Manhattan. A concrete spiral and one of famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright‘s most notable creations, the museum sees just as many visitors seeking to appreciate its architecture as it does visitors coming for the art. Built in 1959, the story of its conception and construction married Wright’s avant-garde design instinct with Solomon R. Guggenheim’s taste for art that pushed boundaries. The building, which was renovated in full in 2005, is one of the most popular destinations in the city’s art scene even eighty years after its opening day. Here are the top 10 secrets we found about the place.

1. Technically, the Museum’s First Location was in the Plaza Hotel

Solomon R. Guggenheim was raised to appreciate the classics. Coming from a wealthy mining family, he had already collected a number of pieces by the old masters when he met artist Hilla von Rebay in 1926. She instilled in him a love for the avant-garde, and he never looked back. Without a suitable place to display his collection, however, Guggenheim resorted set up a makeshift gallery in his spacious apartments at the Plaza Hotel. In 1937, he established the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, the first real iteration of the museum and its governing body.

See vintage photos of the original museum here.

2. The Museum Was Not Called the Guggenheim Until After Solomon Guggenheim Died

Photo: David M. Heald © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Photo: David M. Heald © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Rebay’s influence on Guggenheim and her interest of abstract art is apparent from the museum’s beginnings. It opened in Midtown in 1939 as the Museum of Non-Objective Painting. Rudolph Bauer, Marc Chagall, and Pablo Picasso were among the many abstract artists who found a home at the museum’s first real location. It was only after Guggenheim died in 1949 that the museum was finally named in his honor, christened the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1952.

3. Frank Lloyd Wright Agreed to Design the Building After Guggenheim Sent Him a Letter

Image via Wikimedia: public domain

Given the intensive undertaking that designing Guggenheim’s dream museum turned out to be (involving almost 12 years, 7 different designs, and hours consulting with both Guggenheim and Rebay), one would think that the legendary American architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, knew the pair beforehand. He did not. Rebay and Guggenheim wrote him a letter, Rebay paid the commission, and Wright got to work, eager to try his naturally organic design influences in a stark urban setting. Unfortunately, neither Guggenheim nor Wright lived to see the final product, as the museum that we see today opened in 1959, months after Wright’s death and a full 10 years after Guggenheim’s.

4. Guggenheim’s Longtime Partner, Hilla Rebay, was Forced Out of the Board of Directors After His Death By His Family

It seems every famous partnership has its expiration date. As with lawsuits amongst the founders of Facebook, the infidelity-fueled divorce of the Masters & Johnson team of sex researchers, Rebay’s time with the Guggenheim Foundation was numbered. In reality, Guggenheim’s family did not understand or appreciate Rebay’s philosophical leanings and taste for art as much as Solomon Guggenheim, and as soon as he died, Rebay was forced to resign from her position as director of the museum. She did, however, donate a portion of her personal collection to the museum upon her own death.

5. The Museum Could Have Been Hexagonal

Photo: David M. Heald © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

In all, Wright drew up seven designs for the museum. While six of them adopted the curved spiral that has become so famous today, one of them proposed a series of hexagonal levels without ramps or curves, adopting the conventional staircases and elevators for visitors to get around. Luckily, Wright, Guggenheim, and Rebay decided against it, and the organic spiral plan entered into construction.

6. Wright Intended for Guests to View Exhibits from the Top to the Bottom

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David M. Heald © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Attention, everyone! Wright, in addition to doing away with crowded rooms and interlocking corridors that all but defined all other museums of the day, hoped to create a fluid experience of the art in the museum. He envisioned a glass elevator that would take patrons all the way up to the top, after which they would view exhibits from the top down before finally reaching the last pieces in the atrium. In some way, we suppose it makes some sense. Wright’s elevator would stop us from viewing the pieces backwards when eventually descending the spiral, which in some cases can change the intent of the pieces based on order. But honestly, would anyone really be up in arms about it?

7. The Museum Was Almost Red

In Wright’s original plans, the museum featured a red exterior. Red, Wright maintained, was the color of creation, and a suitable ode to the works of genius the museum would eventually contain. The idea was scrapped, when among other things, the building’s exterior was built with concrete instead of the stone finish that Wright was envisioning as well. See Wright’s original drawing via inexhibit.com.

8. Robert Moses Once Tried to Persuade Wright to Redesign the Building

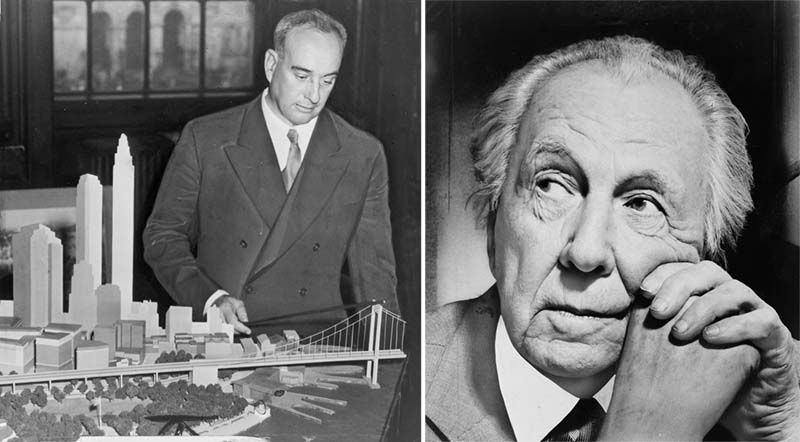

Image via Wikimedia: Robert Moses (left) image via Library of Congress, right Frank Lloyd Wright portrait via Wikimedia: public domain

Robert Moses, city planner extraordinaire and maybe one of the single most polarizing figures in New York City history, hated modern art. Naturally, he hated the design of the Guggenheim Museum, then in construction, and tried to persuade Wright to revise his design into something that fit in with the industrial, hard-square urban landscape that he was already building. On an unrelated, awkward note, the two were distantly related cousins.

9. Many of Wright’s Ideas for the Function of the Building Were Deemed Too Ambitious

Photograph by David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Wright included a number of special features in his plans for the museum building. They included a tower next to the museum that would house artists’ studios and residences, an automatic vacuum system in the lobby so that the visitors would not track dirt on the museum’s floors, and a smaller rotunda to be used as residences for Guggenheim and Rebay. The tower and the vacuums were not financially feasible in the end, and though the smaller rotunda was built, Guggenheim’s death and Rebay’s resignation from the board of the directors prompted the museum to turn the space into storage.

10. The Museum’s Spacious Rotunda Allows for Some of the Largest Installations in History

I Want to Believe, Cai Guo-Qiang, on display February 22 – May 28, 2008

Thought it may not seem like it, the Guggenheim Museum, by virtue of its wide-angle rotunda, houses one of the largest exhibition spaces for art in the city. Many artists have come to use the open air to their advantage, creating some truly spectacular works that not even the MoMA or the Met could hope to rival.

Next, read about the Top 10 Secrets of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Get in touch with the author @jinwoochong.