♀️ The Trailblazing Women of Wall Street

Women have long shaped Wall Street—even when history tried to write them out.

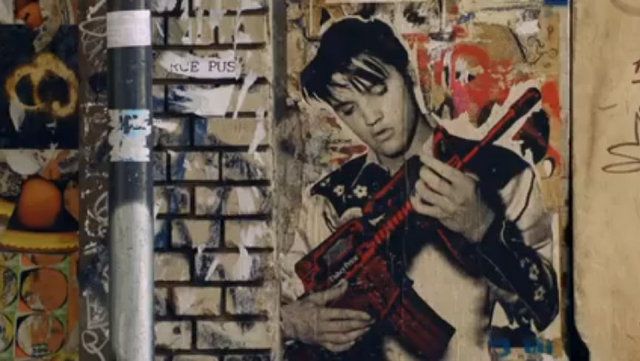

French photographer and filmmaker Gregoire Alessandrini, whose photographs of gritty New York City in the 1990s we have showcased on numerous occasions, has recently uploaded a 30 minute documentary on the ’80s artist and stylist Stephen Sprouse, a film he produced and co-wrote in 2009. Children of the ’90s may be most familiar with Sprouse’s work as the inspiration behind the neon collection that Marc Jacobs did for Louis Vuitton in 2001 which took, among others, the iconic monogram bag and plastered it with graffiti-style lettering.

While on first glance, the later commercialization of Sprouse’s work seems like a contradiction of what the artist stood for, it is fitting that Alessandrini is behind this documentary to show us the nuances, with his experience growing up as the son of rock and roll photographers in New York City. He is a video producer for Louis Vuitton, but he includes in this documentar interviews with New York City personalities like Debbie Harry of Blondie, fashion editor Candy Pratts Price, costume designer Patricia Field (of Sex and the City fame), along with Marc Jacobs, and Louis Vuitton executives.

Debbie Harry of Blondie, speaking in Looking for Stephen Sprouse

The documentary energetically shows the creative energy that was in New York City during the 1980s. As Debbie Harry says, “It was a high energy period, a very creative time. There was no money involved, I think that maybe part of the excitement of it. It wasn’t very a super commercial period. New York City was bankrupt.” In this time, a small circle defined the social scene and nightlife, including people like Andy Warhol, David Bowie, and Stephen Sprouse. It can almost be described as an informal collective, and indeed many of the creative icons of the era were living together, visited by the likes of Mick Jagger, Bowie and more. “People didn’t have to work like crazy to pay their rent, says Mauricio Padilha, co-author of the book Stephen Sprouse, “People were able to pay their rent and do creative things.” It was a time of “spontaneous friendships,” says hairdresser Christiaan Houtenbos and Sprouse was a “fixture of New York nightlife.”

It’s clear from this documentary that Sprouse was so influential within his circle because of his Renaissance-like abilities within the realm of art – from sketches, fashion, to graffiti, video and more – and his strong vision on style. Candy Pratts Price describes it as almost “dictatorial,” but is full of admiration: “Some people see more than others. And I do think he did. He could see in the room much more than any of us could. He could see a profile, a silhouette, a sound, a hair that he thought was col. Looking at his hands was fascinasting for me because they had content of everything. The way he drew his markers. Took numbers on his skin. Everything about that was very hands on, very raw. ”

Sprouse’s vision was clearly ahead of his time – looking at the art and the fashion today, there are his fingerprints everywhere it seems. But at the time, it was “very downtown, very young, very youthful, very rock and roll. Very counterculture,” says Debbie Harry. “Stephen’s clothing was for a very limited market, says Roger Padilha, author of the book Stephen Sprouse, “The people who wanted to wear his clothing couldn’t afford to wear his clothing. The people who could afford to wear his clothing, weren’t brave yet, or daring enough to wear it.”He was using colors not used on clothing yet (on uniforms for garbage men, for example says Padilha) and patterns derived from the art world. In addition, he never changed his aesthetic or products for commercial reasons, or by request like other couture houses do.

There was even a three-floor story in SoHo, at 99 Wooster Street, predating the luxury brands that dot the landscape today. Located in a former fire house, it was an all experience store – if the clothing was camouflage, the store was painted camouflage too. The documentary also intersperses glimpses of an earlier New York City, of streetscapes still there but altered so dramatically, from a cultural perspective.

The only time we hear from Stephen directly in the documentary is at the very end: “Rock, art and fashion were always my favorite things, in that order. But I don’t know how to play anything so I had to work on the other two.” Sprouse died in 2004, after complications from lung cancer.

Next, check out the Gregoire Alessandrini’s photographs of the Meatpacking District in the 1990s.

Subscribe to our newsletter