When Governor Andrew Cuomo moved to shut down New York City’s subways from 1 a.m. to 5 a.m to combat the coronavirus pandemic this past May, it seemed to be a monumental decision. However, it was far from the first time that the city’s subways had been shut down. One such time was the 1966 Transit Strike, when all of the city’s public transportation (not just the subway) was not in operation. Although the subway was closed for different reasons then and now — a pandemic versus labor disputes — they both resulted in similar conversations about the nature of essential work and alternative modes of transportation.

Image of MTA workers sanitizing subway cars in May. Courtesy of MTA.

Image of MTA workers sanitizing subway cars in May. Courtesy of MTA.

The transit strike was called on New Year’s Day in 1966, yet it represented the boiling point for years of labor unrest in New York City. At the end of every calendar year, the Transit Workers Union (TWU) would enter into bitter negotiations with the mayor, threatening to ring in the new year with a strike. In 1960 and 1962, rumors of a strike swirled, yet collective bargaining prevailed and the subways continued to run. However, certain factors remained the same with each passing year.

For starters, the TWU (often in coalition with the city’s other major transit union, the Amalgamated Transit Union) continually focused their demands on the city’s 15-cent fare for all buses and trains. The union demanded that the fare be doubled so that the transit workers could receive wage increases, shorter hours, and other contract improvements. If the fare could not be doubled, then the Union demanded for a larger cut of the city’s budget to satisfy their requests. If that would not be done, then they would strike.

However, even more constant than the union’s demands was their leadership. The TWU was led by Michael J. Quill, the union’s longtime president and a vibrant presence in the city’s politics (check out the New York Times’ comical descriptions of Quill to get an idea). Quill was also a close personal friend of Mayor Robert Wagner, a relationship that surely helped in preventing strikes in 1960 and 1962. However, Quill shared no such camaraderie with Wagner’s successor, Mayor John V. Lindsay, who was set to take office on January 1, 1966. With this, the stage was set.

Quill and the TWU were ready to have their moment in the spotlight, making their demands known once and for all by closing all public transportation in the city on the day the new mayor would take office. The political drama was palpable, yet as the reality of the strike became more and more apparent, New Yorkers began preparing for a New York without mass transit.

Mayor Wagner was a personal friend of Michael Quill, leader of the TWU. Photo from Library of Congress.

Mayor Wagner was a personal friend of Michael Quill, leader of the TWU. Photo from Library of Congress.

According to the New York Times, four to five million people used the subway to get to work, meaning that the strike was going to challenge both the city’s infrastructure and the ingenuity of New Yorkers. As a result, solutions to the transportation problem were varied. New Yorkers organized carpools and some businesses mapped private bus routes to transport employees to their offices. Additionally, commuter railroads that were not affiliated with the striking unions planned extra service to handle the increased passenger traffic.

Even with these transportation alternatives in place, city officials were concerned that the excess of private cars traveling to work would result in “monumental traffic jams.” As a result, additional measures were taken. In a 2 A.M. radio and television broadcast on New Year’s Day, a weary Mayor John V. Lindsay outline a series of emergency plans aimed at minimizing the strike’s negative effect. The new mayor urged severe restrictions on all travel into Manhattan, asking that New Yorkers refrain from all “non-essential automobile trips” and that employers use “skeleton crews of absolutely essential employees“. The mayor also urged employers to stagger the work hours of those who were still required to come in.

With all of these precautions and restrictions put in place, the strike still managed to have a visible impact on life in the city. Many businesses choose to stay open and “provide essential services“, yet some industries and areas were hit harder than others. For example, the Garment District on 7th Avenue in Manhattan suffered “substantial losses in both wages and businesses” as a result of the strike. Similarly, the president of Macy’s department store blamed the strike for “one of the worst days I can remember – worse than any of the snowstorms or blackouts we’ve had“. Even some newspapers were impacted, with many (such as the New York Times) deleting pages from their Sunday runs because of cancelled advertising.

The strike may have apparently been caused by a political squabble, yet it came to be defined by the effect it had on the large majority of New Yorkers. Public sympathy for the strike fell significantly, with even other union members coming to deride Quill and his antics. Yet the political bickering persisted. Quill, in one of many impassioned speeches to transit workers, referred to Mayor Lindsay as a “pipsqueak” and a “juvenile” who was truly the man to blame for the strike’s occurrence. The mayor fired back, condemning Quill for an “unlawful strike against the public interest…an act of defiance against eight million people.”

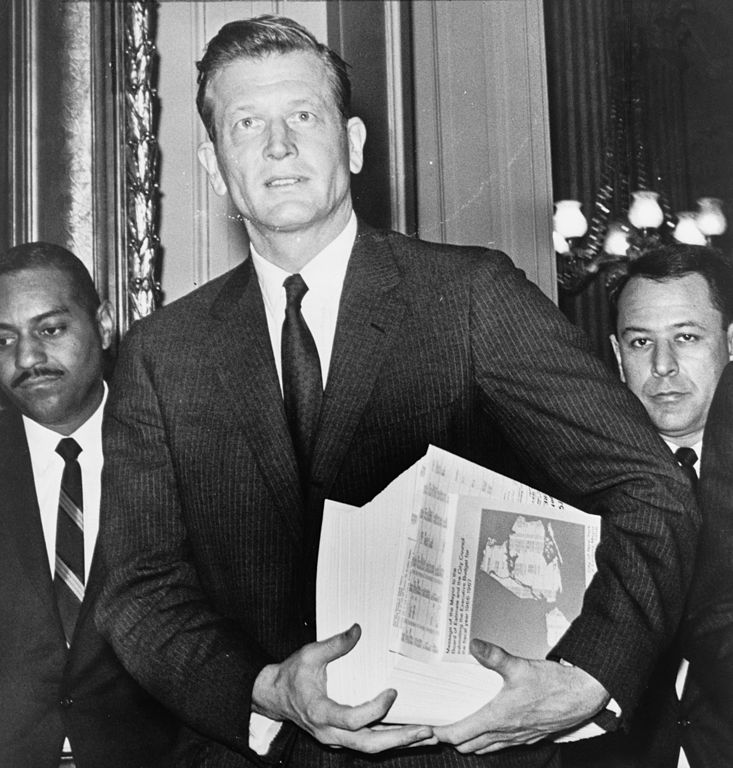

The Transit Strike marked the beginning of Lindsay’s turbulent mayoral career. Photo from the Library of Congress.

Unlawful turned out to be the right word, as Quill (along with eight other union leaders) was arrested on January 4th for organizing the strike. Quill, ever the character, continued to keep the media entertained while in a cell. “The judge can drop dead his black robes,” Quill boldly proclaimed. “I don’t care if I rot in jail. I will not call off the strike.” Yet while Quill may have retained his resolve, the same could not be said for his health. He suffered a seizure while imprisoned and was moved to Mt. Sinai medical center, where he would die later that month. He was succeeded by longtime union member Douglas L. MacMahon, who attempted to retain Quill’s fiery rhetoric by claiming that the strike would continue until “hell freezes over“. Yet despite these strong words, Quill’s absence meant that bargaining was back on the table, and the strike’s end was on the horizon.

The strike ended on January 14th with a settlement that provided a wage and benefit package of approximately $43.4-million to Transit Authority employees under a two-year contract. The strike also resulted in the passage of the Taylor Law, which defined the rights and limitations of public employee unions in New York. The questions of politics and labor that prompted the strike found seemingly neat conclusions, yet the 12 days without public transportation resulted in serious effects on the lives and work of New Yorkers.

Regardless, Mayor Lindsay chose to end the strike with a note of optimism. “I believe the successful resolution of the subway strike may signal the beginning of a fresh and rewarding era in labor-management relations in New York City; aa time in which rectitude candor and objectivity implement the essential soundness of collective bargaining procedures,” said the mayor. “Our guiding principles, I hope, will be service to the people of this city, service to their needs, their wants, and their spirits. It is a principle I shall long pursue to the best of my ability, so long as I hold the office of Mayor.”

This hope would turn out to be quite far from reality. Lindsay’s time in office would be plagued by labor disputes, such as the 1967 and 1968 Teacher’s Strikes, the 1968 Sanitation Strike, and the 1971 Police Strike, the last of which utilized the Taylor Law to limit labor’s power and which shares similarities with contemporary issues about policing in New York City. The 1966 Transit Strike was a turbulent beginning to a turbulent mayoral career for Lindsay. It marked a time in which the city experienced much turmoil and during which the necessity of institutions, and the reliance of New Yorkers upon those institutions, were tested.

Although it may be the result of wholly different circumstances, New York’s current experience of the coronavirus pandemic bears resemblance to, and can perhaps learn from, the experiences of New Yorkers during the 1966 Transit Strike. The process of defining essential work, the ingenuity involved in finding alternative modes of transportation, and the commitment of New Yorkers to adjusting their lifestyles all find renewed meaning in our current moment. With this, the 1966 Transit Strike stands as a curious yet meaningful example of how New Yorkers can persevere in the face of forces that remain beyond our control, be it labor disputes or global pandemics.