In March, I traveled to Germany’s Ruhr Valley (Ruhrgebiet) as a teaching assistant for an urban planning studio at Columbia University. The purpose of the studio was to look at a small site in the city of Bottrop along the Emscher River, a river that has been used as an open sewage canal for over a century. For eight days we explored sites in the region to understand the planning and economic transformation of the Ruhr.

The Ruhr Valley is located in the central part of the German state North Rhine-Westphalia. Naturally located on major coal deposits, the Ruhr region was once an industrial powerhouse and the center of the 1950s and 60s German “economic miracle.” A structural crisis in the 1970s meant that German coal was no longer in high demand and overseas competitors were able to undercut the domestic steel production facilities. Once boasting the majority of coal mining in Germany with almost 300 mines, the Ruhr Valley now has just three. These remaining mines are only operable because of German federal subsidies, which are planned to be phased out in the near future.

Just like the rust belt of the United State, this shrinking area has been forced to rethink what will drive its future economy. Rather than allowing these large industrial sites to rust, many of these abandoned mines are being transformed into new uses. While retaining many of the historical buildings, the Germans are eager to build on these sites rather than looking at vacant green spaces as an option. One amazing site we got to visit was the former Zeche Lohberg plant in the city of Dinslaken. Zeche Lohberg was built between 1907 and 1924, along with the surrounding town as part of the garden city architectural movement. The coal mine’s footprint is about 300 acres, along with a multiple, massive slag heaps where industrial waste from the coal process was stored. The mine was operational until 2006, and unlike other sites that are further along the transformation process, Lohberg is just at the beginning.

Nine of the buildings on the site are now listed for historic preservation, and different uses and plans are being worked out to hopefully create new housing, spaces for businesses and a fresh identity for the area. Our group was given a tour by local experts Ruth Reuther, a local city council member, and Bernd Lohse, a representative of the site’s current owner RAG Montan. Their vision is to transform Lohberg into a new neighborhood with space for apartments and businesses, and where creativity and businesses can flourish. As they realize that this may take a while, they have allowed for intermediate uses to take over space, a special concept in German planning. This means they allow people to lease the space temporarily as construction and future planning take place and evolve overtime.

The first building we entered was the administrative building. As you enter the main hall you can see a square room where the plant managers and foremen had offices. This room also had a long window where staff would pay the workers every Friday. All are connected by a large hall, about 30 feet high and completely lit by roof lanterns. At one end of the hall was a massive mural, perhaps 30 feet wide by 20 feet high represented the main industry of the area, a farmer, a steel worker, and a coal miner. Our guides explained that the mural was created in 1956, a time when the plant was reaching peak output. Each Friday as the workers entered this room to receive their pay, this massive mural loomed over them, instilling pride in the workers. Whether this was designed as propaganda for the workers or not, it now serves as a historical marker for understanding the industrial past of the site.

Upstairs we toured former offices that are being converted to spaces for new businesses. One of these spaces was use by an artist, who explained she loved the light the building captures, allowing her to make wonderful art. She has converted the space into a studio and a classroom. She hosts classes for people in the area, of which she was hosting one as we came in. The women that take part in this class never imagined that such a space could be created out of the former coal mine, and they enjoy the creative community that is forming there. Other spaces that have been refurbished include craftsmen and architects.

Next we moved through the wing of the building that the coal miners themselves would move through at the beginning of the shift. This long hallway is full of small lockers that the miners used to store small belongings, keys or wallets. The lockers still had memorabilia attached, small stickers that workers used to personalize their space. Our guide explained that each locker represented a job that was lost when the plant closed.

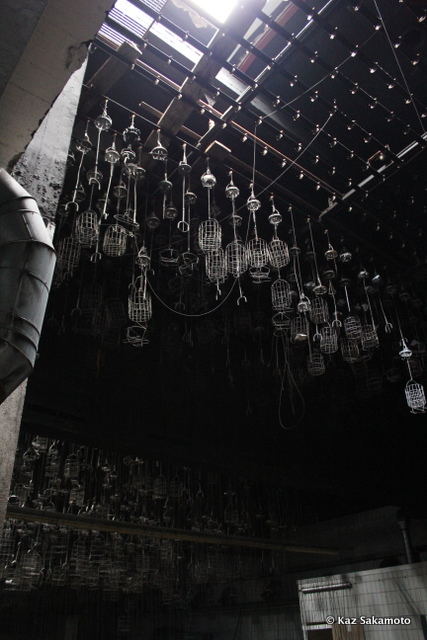

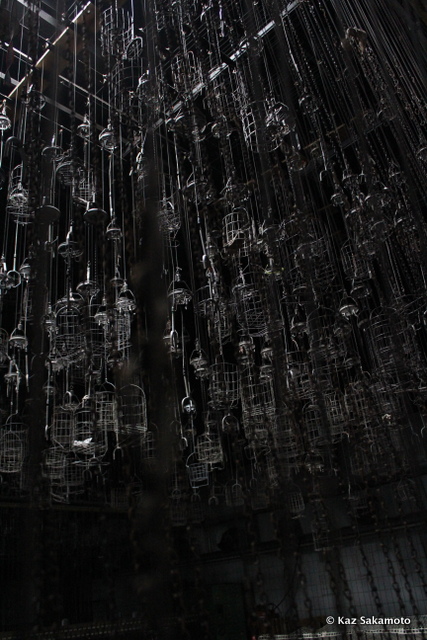

Upstairs was the final room the coal miners used before entering the mines. Entering the large concrete space, a few shafts of light broke through to show the vastness of an empty room with hundreds of metal baskets hanging from the ceiling. It might look like a modern art installation, but these baskets were where the miners stored their dirty work outfits. Like the lockers below, each of these baskets represents a miner, like abstract ghosts hanging above. The feeling in the room, down to the stillness in the air, was chilling. However as unsettling as it was, I wish this room could be preserved, if for nothing else than to illustrate the routine of the coal miner.

To go to the next building we had to traverse across the site and around the former mining machinery and major equipment. Once outside we got a sense of how large this site is, and the economy of scale that is required to run such an operation. The large steel shaft tower contains the machinery that pulled the coal out from underground. Although expensive to keep it standing, it was decided that the building must be preserved as symbol of the former coal history. These buildings are present at former mines and plants all over the region, a common sight on the landscape, however each one is slightly different, with different colors and names to distinguish them.

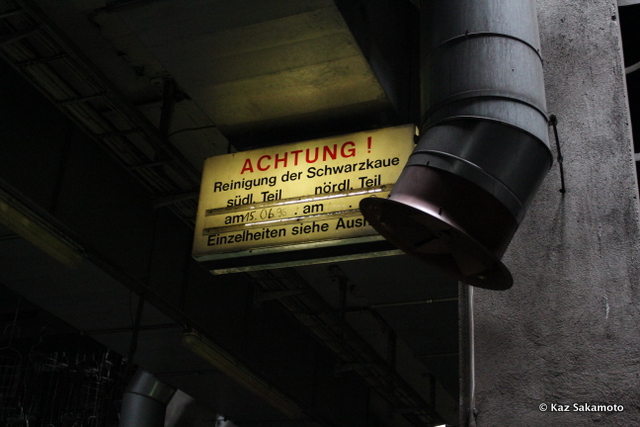

Adjacent to the shaft tower is a coal washing room. The style of architecture is important to note, because many industrial sites in Germany were completely destroyed in World War II. This building was able to survive the war, and has the intricate red brick masonry and curvy gothic style windows discarded at similar sites built in the latter part of the century. The building is very horizontal, rising only twenty 25 or 30 feet high, but stretching maybe 100 yards. The space was so raw, but still retained many work signs and some equipment on the sides. The abundant and tall windows on the side allowed an amazing amount of light in, despite no power being in the building currently. As we walked around we saw a small group of architects taking measurements and notes to find out what necessary steps would be needed to repair the building.

The final building we toured on the site was where the coal was mixed with a special stone to become coke and increase its burning capacity. This process was pioneered in the area and helped fuel the blast furnaces for the local steel plants. It’s a massive building, allowing trucks to move the materials in and out. The curved roof makes this building feel very different, almost masking your ability to guess what decade it was built. Ruth and Bernd explained that no future use has been decided for this building but that it has been decided to be preserved. The space is so large that a full soccer field could be put inside.

The last part of the tour was on the site’s former slag heap, where industrial waste from the coal extraction and filtration process were stored. No longer being used to store waste, the area is slowly being planted by different plant species as experiments to see which can grow and which can bio-remediate the soil. All hills in the Ruhr are slag heaps, artificial landscapes created by its industrial history. These hills provide magnificent views of the active industrial sites, open spaces and small skylines of cities that populate the region. The natural succession of these slag heaps and transformation of this landscape is similar to the approach the people have with the former mining buildings on the site. An untrained eye looking at Lohberg may only see a dump, but it was clear from Ruth and Bernd’s attitude that they only see a positive future taking shape here.

The reuse of historical sites is certainly not unique to Ruhr area of Germany, but it is amazing to see the planning process as compared to that in America. The plan is structured similarly to the United States, but they tend to take less of a strict vision of exactly how it is to be reused and allow for evolution to take place on the site. The idea of having temporary uses, and allowing construction and planning to happen simultaneously is unique. As we move from fossil fuels to cleaner energies, and larger production facilities to smaller ones, we must consider how our former spaces will be used. Maybe we can take a lesson from the Germans!