Syrian refugees in El Qaa, Lebanon, 30 meters from the border with Syria

Syrian refugees in El Qaa, Lebanon, 30 meters from the border with Syria

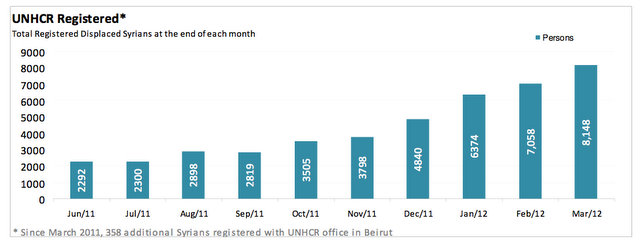

Over 8000 displaced Syrians have streamed into north Lebanon since the beginning of Syrian President Bashar Assad’s brutal crackdown of Sunni rebels. While the violence in Syria continues unabated, Syrian refugees who managed to escape Assad’s forces paint a gruesome picture of abuses and killing of civilians and military-aged men that some have compared to Srebrenica.

What is surprising, however, is that despite rapid the influx of Syrians into northern Lebanon – more than 3000 this month alone – there are no major refugee camps in northern Lebanon. Instead, displaced Syrians are being “absorbed” into predominantly Sunni northern Lebanese villages. According to the UNHCR, the majority of the refugees reside with “host families” rather than in camps – a welcome development since refugee camps are often characterized by overcrowding and permanent slum-like conditions.

Photojournalist Steven Wassenaar, who recently visited the Bekaa Valley describes the relations as being very close between the new arrivals and existing Lebanese due to strong Sunni to Sunni solidarity in northern Lebanon.

Family of Syrian refugees who arrived on March 4 in the village Wadi Khaled, Lebanon

Family of Syrian refugees who arrived on March 4 in the village Wadi Khaled, Lebanon

Lebanon’s history with Syria has been contentious since before the Lebanese Civil War began in 1975. Syria armed Palestinian militias in Lebanon as early as 1969 and by 1976 commanded a “peacekeeping force” in Lebanon under the auspices of Arab League. In 1991, a Treaty of “Brotherhood, Cooperation, and Coordination”, signed between Lebanon and Syria, legitimized the Syrian military presence in Lebanon. By 2000, Syrian control faced increased resistance from the Lebanese people and was forced to announce its full withdrawal from Lebanon on April 30, 2006 after the assassination of ex-Premier Rakik Hariri.

El Qaa, border between Lebanon and Syria. Syrian refugees have to cross this border, a very hazardous move because of landmines

El Qaa, border between Lebanon and Syria. Syrian refugees have to cross this border, a very hazardous move because of landmines

Against the backdrop of this political history is the complicated reality of great income inequality between the Lebanese and Syrians. Syrians in Lebanon often work as working class laborers and migrant workers in construction and farming. In northern, predominantly Sunni Lebanon, however, Syrian migrants have been working and traveling between the countries for years, doing business and trading with local Lebanese as one people. In fact, many Syrians who worked in the construction industry as migrants before the conflict are now living in the same unfinished homes they were helping to construct.

Family of Syrian refugees who arrived in March in the village El Fakha, Lebanon, after escaping violence in Zahra (Syria). They now live in a house that is still under construction.

Family of Syrian refugees who arrived in March in the village El Fakha, Lebanon, after escaping violence in Zahra (Syria). They now live in a house that is still under construction.

To be sure, not all of Lebanon is welcoming Syrian refugees with open arms and there are reports that Shiite-dominated Hezbollah has even delivered refugees to the Syrian army. But outside of the political class, as always, the reality on the ground is very different to the people it most directly impacts. Syrians have found rooms, homes, and mosques in Lebanon, sometimes for pay, often for free. Whole refugee families often stay in one room and have trouble finding work, but sharing seems to be the general atmosphere. One Lebanese man asked Wassenaar, “what is one more bed and one more mouth to feed?”

Syrian refugees who live together with other families in a school, Wadi Ghaled, Lebanon

Syrian refugees who live together with other families in a school, Wadi Ghaled, Lebanon

The refugees tell stories of mass slaughter and families arrive often comprised only of women, children, and the elderly after witnesses their sons and husbands executed in front of them. Wassenaar has photographed refugee camps in the Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi, but was struck that the Syrian children, so fresh in their sorrow, fail to smile even when handed candy.

Most of the men who did make it to Lebanon vow to go back and fight against the Assad regime once they situate their families. Others find work, but plan to return after Assad’s government falls.

Hamzi is a 9 years old boy who was injured after an exploding shell in Zahra made him fall. He is part of a family of Syrian refugees who arrived in March to the village El Fakha, Lebanon, after a bombardment on March 9th, 2012 that destroyed their house in Zahra.

Hamzi is a 9 years old boy who was injured after an exploding shell in Zahra made him fall. He is part of a family of Syrian refugees who arrived in March to the village El Fakha, Lebanon, after a bombardment on March 9th, 2012 that destroyed their house in Zahra.

What may best explain the unique refugee hosting then, may not just have to do with familiarity, but the unifying force of a common enemy. For over 40 years, Syria, led by the Assad family exerted control over Lebanon in one form or another culminating only when it was thought to be involved in the assassination of a very popular Lebanese leader in Hariri. Despite socio-economic differences between Syrians and the Lebanese, today’s camraderie may best be explained by a popular Arab proverb, “my brother and I against our cousin, my cousin and I against our enemy.”

Follow Untapped Cities on Twitter and Facebook. Get in touch with the author @surajstar.

Special thanks to Steven Wassenaar for the use of these photographs. For more images, please see his website. Wassenaar’s work treats themes such as (post)- conflicts situations, exclusion, poverty and immigration. He recently worked in Syria, Lebanon, DR Congo, Rwanda and Mali. He collaborates with NGOs such as Médecins du Monde and Solidariré Sida and publishes in newspapers and magazines from Holland and France. Steven Wassenaar is a member of the NVJ (Dutch Association of Journalists) and the NVF (Dutch Association of Photojournalists).