Lagos, Nigeria, has a Bus Rapid Transit system, is constructing improved rail, beautifying its highways, rebuilding the port, developing the waterfront. Yet is has a reputation for crime and mayhem which seems hard to shake. Just how menacing is it?

Uniformed policemen tried to carjack us in a crowded market in broad daylight. Our driver careened through the winding streets to escape, with the help of the crowd and the traffic around us. Here is our escapade in Africa’s fastest-growing city.

We had arrived a bit apprehensively in Nigeria, but were intent on seeing Lagos, a relatively new megacity that is expected to grow to 24 million people and become the world’s third largest city by 2030. The current population of 15-18 million is already overburdening the existing infrastructure. Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, however, has faith in the city’s strengths, arguing that Lagos, in all its hyperkinetic energy, has much in common with what he famously called Delirious New York: “Lagos is not a kind of backward situation but an announcement of the future,” says Koolhaas, adding that it has a “strange combination of extreme underdevelopment and development.” Certainly Lagos has an over-the-top vitality that can be reminiscent of New York, combined with legendary traffic jams of every type of vehicle (it can easily take 3 hours to cross the length of the city). Yet the traffic congestion provides a major entrepreneurial opportunity, enabling vendors to sell all manner of goods to those stuck.

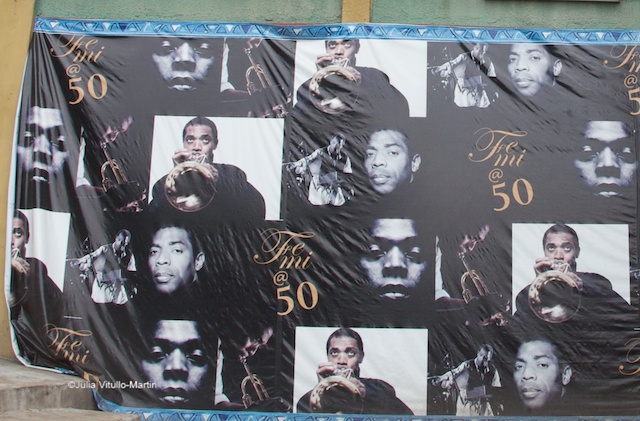

Fela’s Shrine

As New Yorkers and fans of the recently closed (but soon to be on-tour) Broadway show Fela!, we decided to start our visit to what is probably Africa’s most famous nightclub-The New Afrika Shrine. The story of Fela Anikulapo Kuti, the musician who pioneered Afrobeat, can be called wild by any terms. Born in 1938 to Yoruban parents-his father was an Anglican pastor, his mother a women’s rights activist-he combined his bold, innovative music with ongoing defiance of Nigerian governments.

On February 18, 1977, the government sent some 1,000 soldiers to Fela’s commune, which he called the Kalakuta Republic, where they brutalized and assaulted his followers, and beat him so badly he was left with two broken legs. They threw his mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, from a second-story window, almost surely precipitating her death. More trouble and rebellion for Fela followed, including an 18-month prison term. Over a million people attended his funeral when he died in 1997.

After his death the Shrine was resurrected-and is now run-by one of his sons, Femi. It is forbiddingly full of “area boys,” vaguely organized petty criminals and gang members. Lagos journalist Onche Bishop Odeh told us not to worry-that these area boys were “pretty well behaved” -but it was hard to tell.

Building Infrastructure

Heading east-slowly-on the breathtakingly congested Ikorodu Road, we were impressed with the Bus Rapid Transit system, Africa’s first. Those buses really move, and almost no cars venture into their lane since the fines are steep. The few that do get out fast. Motorcycle taxis (okada), on the other hand, zip in and out jauntily, though we never saw them slow a bus down. Lagos is also served by some 75,000 minibuses (danfo) plus a few mid-buses (molue) and shared taxis (kabu-kabu). But even the best BRT wouldn’t be able to solve the megacity’s huge congestion problems. Instead, Nigeria is building a light- and high-speed rail network, partly financed by the Chinese government, to connect Lagos with other cities. New rail is a bold move, notes Professor Elliott Sclar of Columbia University: “Metropolitan planning for transit has begun to make a difference in East Africa-look at Nairobi-and may pay off in West Africa.”

Ominous Crime

Sound as its transport policies are, they won’t be enough to catapult Lagos forward out of poverty unless it tackles crime-and what George Packer in the New Yorker called its “fearsome reputation among Westerners and Africans alike” for official shakedowns, swarming touts, armed robbers, con men, and corrupt policemen.

We had read about Lagos State Police shakedowns-and the attempts by the much-respected governor, Babatunde Fashola, to put a stop to them. But our driver said repeatedly that they were a way of life. Indeed, the US Department of State actually warns about “violent crime committed by individuals and gangs, as well as by some persons wearing police and military uniforms.” As we were driving sedately through a downtown market, the threat materialized: a brown-uniformed policeman came running toward us, hit the car, and yelled at us to park. Shouting “thieves and robbers,” our driver kept going, as a second policeman came from the left and tried to pull open my door. They commandeered two motorcycles, eventually forcing us over behind a traffic jam. But a crowd gathered, impeding them as they tried to flatten our tires. Suddenly the van driver in front pulled to the side, waving us through. The traffic closed behind us, re-establishing the jam, and the cops were stopped. We escaped.

But wouldn’t the police punish the van driver and the others? we asked. No, said our driver, because too many citizens saw what happened.

Just what did happen? It’s not clear-though every Nigerian we asked said the same thing: our driver was right to run. At best the police would have robbed us of $200 as a cash fine-more if they sensed good pickings. They almost surely would have beaten our driver.

What is one to make of Lagos? Ultimately, Rem Koolhaas is probably correct: it is beyond our grasp and surely beyond our individual control.

Get in touch with the author @JuliaManhattan.