Many of today’s visitors who go to the Bois de Vincennes as an escape from Paris’s crowds and buildings would have trouble imagining it as it was in 1931, when dozens of buildings crowded around the Lac Daumesnil and thirty-three million people visited in a six month period. This is where the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition, the apex of interwar political spectacle, was held, and while poster reproductions and old postcards aren’t hard to find today, almost all the buildings constructed for the event were quickly demolished or moved elsewhere.

The Palais de la Porte Dorée is a notable exception to this. Designed by Albert Laprade with bas-relief by Alfred Janniot, this structure at the entrance of the Bois de Vincennes was designed to be the exposition’s lasting monument, a built celebration of the French Empire.

Walking from the metro, the Palais de la Porte Dorée is preceded by a gilded sculpture set atop a series of stepped basins. Unusually for Paris, the figure and its waterless fountains are surrounded by palm trees; their origin as centrepiece to the Exposition’s main entrance provides an explanation for the plants and the group’s positioning here, in what I imagine must seem an incongruous position to those who approach unaware of the area’s history.

The Palais de la Porte Dorée is monolithic, and makes quite an impact when first approached. The basic structure is intended to resemble a classical temple, and the facade, raised two storeys and colonnaded, is covered with two hundred and fifty figures of people and animals.

This is one of the most significant pieces of colonial propaganda ever commissioned by the French government. Janniot’s bas-relief took four months of work for a team of sculptors, and measures eighty-eight by fourteen metres. France’s African colonies are depicted to the left of the main entrance; the Asian colonies are on the right. Abundance, Peace, Liberty are all personified above the door, shown underneath the sun.

The Palais de la Porte Dorée, and the 1931 Colonial Exposition more broadly, were intended to reinforce preexisting politically convenient ideas of life in France’s overseas territories. For this reason, people were shown as living idyllically among nature, alongside exotic animals. Intended both to remind visitors of colonial exports and quell suggestions of exploit, France’s colonial subjects were shown as happily engaged in manual labour, surrounded by the raw materials each region provided, from coal to coco oil.

After the Colonial Exposition, this building housed the Musée de la France d’Outre-Mer, ancestor of the Musée du Quai Branly. Since 2003, it’s hosted the Cité Nationale de l’Histoire de l’Immigration in the upper floors and an aquarium in the basement, but the most spectacular parts of the Palais de la Porte Dorée are on the main floor, and open to the public free of charge.

The spectacle of the facade is continued inside, with decoration covering almost every surface. While the lobby has been adapted for its present use, at either end are well-preserved reception rooms from the Exposition furnished by Eugène Printz and Jacques-Êmile Ruhlmann. Printz’s room is covered in frescoes inspired by Confucian thought, while Ruhlmann’s draws from France’s colonies in South East Asia.

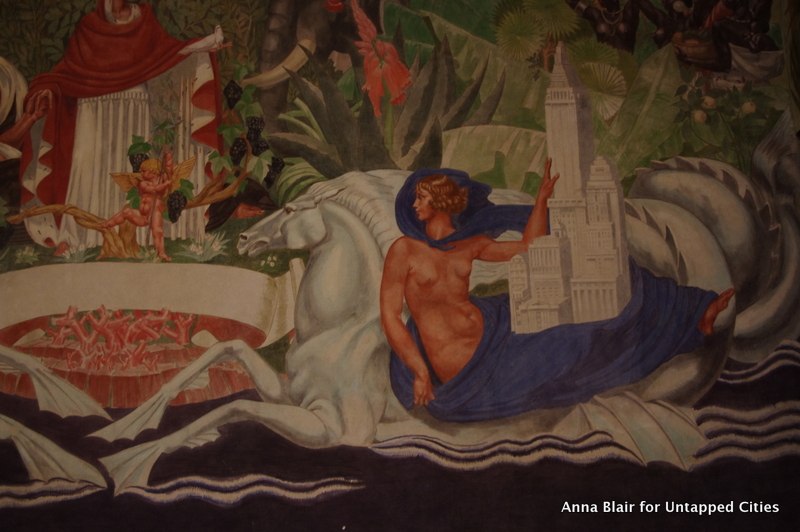

At the centre of the Palais de la Porte Dorée is a large banqueting hall, originally inspired by Moroccan architecture and designed as an open courtyard. The bas-relief of the facade is echoed here in the frescoes of Pierre Ducos de la Haille. These images, many of which are allegorical, celebrate the contributions of France to Industry and Art, and show the nation as supported by its Asian, Pacific, African and American colonies.

The floor is elaborately tiled, and the dark business of the room’s lower half gives way at the building’s third storey to a light filled modern interpretation of an Indochinese pagoda that sometimes offers the suggestion that the roof is almost light enough to float away. At ground level, a number of the scenes illustrated on the walls are peppered with ships, offering the room an overall suggestion of movement.

In two corners of this room are small displays on the 1931 Colonial Exposition, including a model of the Bois de Vincennes as it was for the event. The Palais de la Porte Dorée is remarkably small in this display, which acts primarily to astonish visitors at the scale of the Exposition more broadly. The buildings included a three-tiered model of Angkor Wat at two-third scale, in which visitors could visit exhibits on the restoration of the building’s Cambodian counterpart.

There is another reminder of the 1931 Exposition; a monument to its commissioner, Marechal Lyautey, lies across the street from the Palais de la Porte Dorée. Interestingly, while remainders of the Exposition are thick around the site’s entrance, the Bois de Vincennes itself shows few signs of its past role in colonial propaganda; today, its lakes and lawns are interrupted only by joggers and families on casual strolls, not faux-Tunisian towers. One place where you can still see remnants of France’s colonial past is in the Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale on the Eastern edge of the Bois de Vincennes.

Get in touch with the author @annakblair and check out her blog, Flappers with Suitcases.