Chelsea Market was once part of a sprawling complex owned by the National Biscuit Company. Nabisco, which produces everything from Oreos to Saltines, remained in the complex from 1898-1959. While the Chelsea Market is more of a paradise for gourmands than a factory these days, its pride in its past ensures that historical remnants are readily accessible to the casual visitor. Join us as we take in everything from its steampunk-chic aesthetic to the memorabilia on display throughout the market!

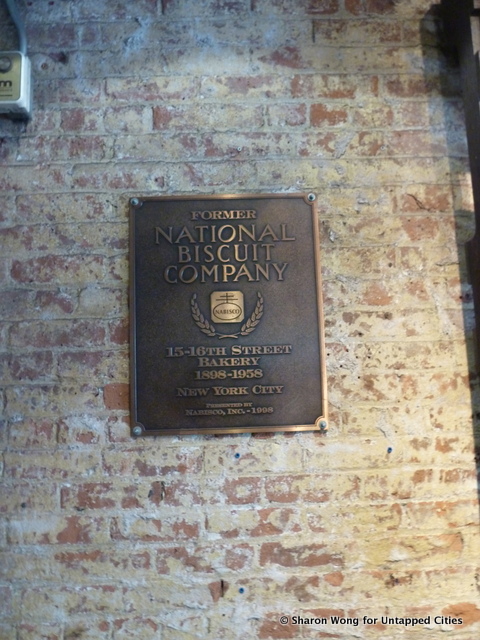

When you enter Chelsea Market from 9th Avenue between 15th and 16th Streets, one of the first of these clues is this brass Nabisco plaque situated right at the very busy entryway. The plaque dates from 1898, the year the New York Biscuit Company and the American Biscuit and Manufacturing Company from Chicago overcame their rivalry to join and form Nabisco, which eventually manufactured half the biscuits in the country. Their consolidation meant that there needed to be more space.

The original complex of six-story bakeries on the east side of 10th Ave between 15th and 16th was expanded all the way to 9th Avenue within a few years, gradually acquiring outliers like the American Can Company building on 447 W 14th St. The designer of these structures, Albert G. Zimmerman, also built the 11 story structure from 10th to 11th Ave and 15th and 16th St. This last structure was built on a landfill, where excavators found the timbers, anchor and chains of an old schooner!

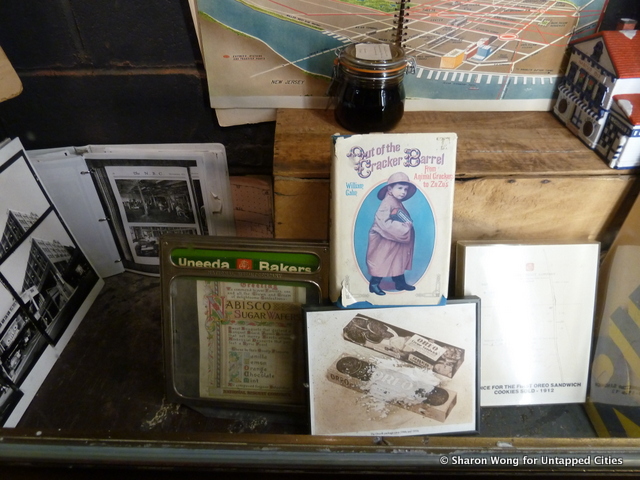

Inside, you’ll see a display case to your right, filled with assorted vintage Nabisco memorabilia, including old Saltines tins, vintage advertisements, and even a clock.

These decorative yet functional advertisements were instrumental in ensuring Nabisco’s monopoly over the biscuit-making industry. The three elements the company was very dedicated to were consistency, shelf life and packaging. All of these containers feature attractive, iconic appearances that draw the eye and imprint easily onto the mind. The streamlined cases are practical, non-intrusive additions to any kitchen shelf that have the added bonus of keeping biscuits well and lasting long, as we can see from these well-preserved specimens.

If you’d like a more macroscopic idea of the factory’s beginnings, the hallway leading out onto 10th Avenue is lined with a plethora of mementos from Chelsea Market’s past and present.

It seems like the building looked much the same as it does now, save for the multiple chimneys billowing black smoke into the air. The famous Art-Deco skybridge across 10th Ave is also noticeably absent. It was only added in the 1930s by the firm’s architect at the time, Louis Wirsching Jr., to connect the factory with the offices across the street.

There are black and white photographs of the old elevated railroad that has now become the Highline and the interior of the factory as it used to be. The idea of constructing a building around an elevated railroad was also Wirsching’s idea. Erected in 1932, the structure features a striking open porch on the 2nd and 3rd floors to accomodate the tracks that still run through.

Interspersed in this exhibit are little tags with the names of the restaurants that now occupy the former factory space:

However, more remains of the old biscuit factory than photographs. You can actually still see the original Nabisco murals right by Ninth Street Espresso. One features the mascot of a boy in a raincoat and the other is another advertisement for Oreos.

There is also the iconic fountain constructed out of discarded drill bits and an exposed pipe. Just like Chelsea Market itself, it is a fine example of adaptive reuse, the practice of using existing materials and structures for functions totally different from their original ones. The whole process is essentially recycling on a large scale, a creative, edgy way of reducing both industrial wastage and urban sprawl.

Throughout the market, there are other decidedly vintage looking fixtures, like this switch compressor and a strange looking light.

It’s hard not to feel like Chelsea Market has both changed drastically and remained much the same. It may no longer be a hub for biscuit manufacturing, but its culinary offerings continue to entice foodies from across the country and the globe. And as upmarket as it has become, it has made the remnants of its industrial beginnings an asset rather than something to be built over and forgotten.