Jazz music originated in New Orleans during the early 1900s, with African-American musicians creating the music style to celebrate their heritage while still striving to fit into the wider American music scene. As the 20th century progressed, the country’s youth began to crave more exciting music and jazz rose to fill in this desire. By 1917, due to a variety of factors including the Spanish flu pandemic, New Orleans jazz musicians began to leave for Chicago. However, jazz music’s popularity in Chicago declined during the 1920s, and musicians migrated again, this time to New York City. After the election of Jimmy Walker as mayor in 1926, speakeasies—establishments known for encouraging free discussions and the sale of bootleg alcohol—were made legal, coming to serve as the perfect breeding ground for the rise of jazz. Learn more about the overlap of jazz culture and speakeasies across New York City, and listen to original recordings from iconic jazz clubs of NYC, on our “Legendary Jazz Clubs of New York City” virtual tour which can be viewed in the Untapped New York Insiders on-demand video archive.

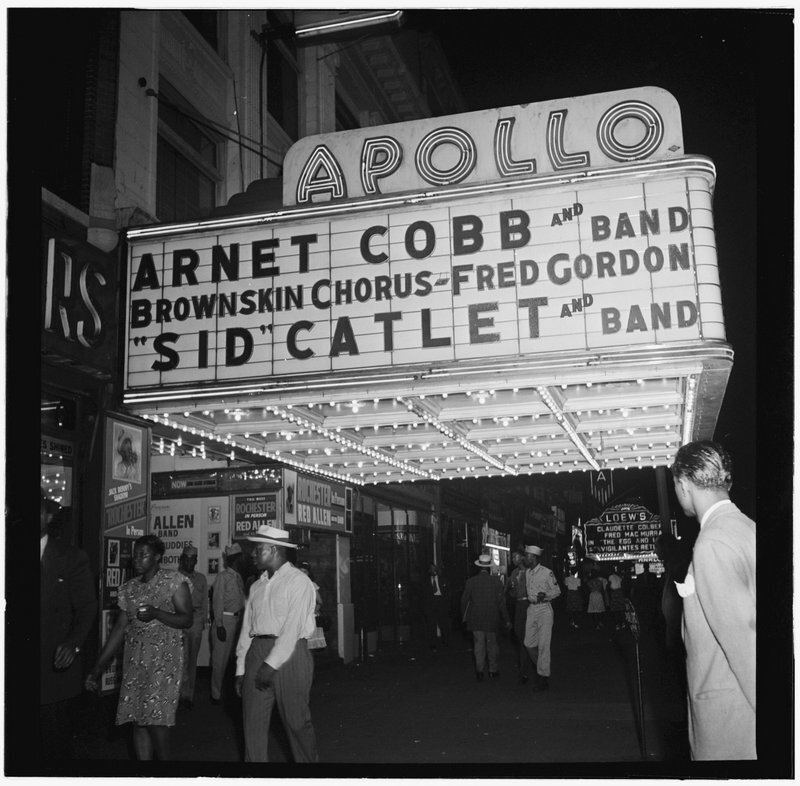

As jazz took hold of the New York City music scene, clubs arose throughout the city to satisfy the growing demand for one-of-a-kind performances. From the Cotton Club – which hosted Duke Ellington’s Orchestra – to the Apollo Theater, which helped start the career of Ella Fitzgerald, these jazz clubs transformed New York City into a haven for jazz musicians. Read on to learn more about the legacy of some of the most famous jazz clubs in NYC, both past and present!

1. The Cotton Club – Past

The Cotton Club first opened its doors in 1920, known then as the Club Deluxe, under the leadership of heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson, who rented the upper floor of a building on the corner of 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue in the heart of Harlem. Bootlegger and gangster Owney Madden took over in 1923, changing its name to the Cotton Club. Soon after, Johnson and Madden entered into a partnership together in which Johnson remained the club’s manager while Madden was free to use the space as a venue for selling alcohol illegally during the Prohibition Era. Though the Cotton Club only operated for two decades, it came to serve as a cultural hotbed, grooming some of the era’s greatest jazz musicians including Duke Ellington, Dorothy Dandridge, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong. At the same time, the Cotton Club remained a whites-only establishment—with rare exceptions made only for Black celebrities such as Ethel Waters or Bill Robinson.

Reflecting the socially accepted racist ideologies of the time, images of Black people hailing from exotic jungles or as slaves working in the Deep South on plantations were visible throughout the establishment. One prime example of this could be viewed in a 1938 menu which displayed illustrations of naked Black men and women dancing around a drum in the jungle. Poet and social activist Langston Hughes famously critiqued the Cotton Club after visiting the establishment, calling it a “Jim Crow club for gangsters and monied whites.”

Every year, the Cotton Club would host two musical revues, which consisted of dance, singing, and comedy acts displayed for the chance of eventually becoming a successful Broadway show. These musical revues would go on to help jumpstart the careers of many artists such as Andy Preer who led the club’s first house band in 1923. From 1927 to 1931, the Cotton Club’s house band switched to Duke Ellington’s Orchestra and in June 1935, the club’s doors were finally opened to Black patrons. After the 1936 Harlem Race Riots, the Cotton Club temporarily closed but reopened later that same year at a new location on Broadway and 48th Street. Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Calloway would go on to lead the club’s most extravagant revue on September 24, 1936—featuring 130 performers. Robinson’s participation ended up costing the club $3,500 a week, the highest salary ever paid to a Black entertainer in a Broadway production.

Eventually, amid rising rent prices and a federal investigation into tax evasion by numerous Manhattan nightclub owners, the Cotton Club was shut down permanently in 1940. The Latin Quarter nightclub soon took its place, focusing on hip hop, reggaeton, and salsa music with similar vibes that matched its fiercest competitor, the Copacabana. Since its closing, the Cotton Club has been heavily featured throughout American pop culture, with examples including the music video for “Oye Como Va” by Cuban-American singer Celia Cruz, Francis Ford Coppola’s 1984 film The Cotton Club, and a 2013 episode of White Collar entitled “Empire City.”