In the fall of 2020, the Wolakota Buffalo Range on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota welcomed 100 wild bison to their nascent herd. The Wolakota project is one of many examples of bison being reintroduced to Native lands all over North America. The animal’s long journey home has taken well over a hundred years and it could not have happened without an unexpected detour through New York City.

Before America manifested its destiny westward in the early 1800s, there were tens of millions of bison roaming the continent. “It would have been as easy to count the number of leaves in a forest,” wrote William Hornaday, the founder of the modern-day Wildlife Conservation Society, as to calculate the number of bison. By the late 1800s, however, the species came perilously close to extinction due in large part to a systematic and brutally effective extermination campaign.

In 1889, Hornaday conducted a census of living bison and found that only 1,091 remained in the entire world, mostly in private herds. This species that grazed the continent for centuries, fed indigenous nations for generations, thundered in mile-long herds, shaped the landscape everywhere it went, were recently as plentiful as the leaves in a forest, were all but gone.

Of course, this didn’t happen by accident. The animals were under attack. Killing bison meant harming and subduing Indigenous peoples, tribes like the Lakota Sioux, who had relied on these animals for centuries. Beyond nutritional value, the animals provided shelter, tools, medicine, a valuable trading commodity, and an oversized space in Native American mythology. For example, a Lakota creation myth says that man and bison walked out of the ‘wind cave’ together into existence. This interspecies relationship worked incredibly but barely survived one generation of exposure to the American dream.

To be sure, the slaughter wasn’t just happening in South Dakota, but all over the West. Hornaday had seen the bison destruction himself on a visit to present-day Montana, where he had made the trip to hunt bison in order to display them. It admittedly sounds odd that the man who would end up saving the bison was also the one hunting down some of the last living specimens. However, before Hornaday was a world-famous conservationist, he was a world-famous taxidermist. To his thinking, a display could at least show future generations what bison looked like, and maybe serve as a grim reminder of extinction’s finality. Unfortunately, Hornaday couldn’t find many living bison. The plains these animals once roamed were instead littered with bones and carcasses. The profound waste weighed on Hornaday, who returned home determined to save the bison.

Hornaday was eventually able to acquire 24 living bison, which took part in a “living exhibit” at the Smithsonian National Zoo in Washington, D.C. Soon, Hornaday would move to New York City to establish a zoological park that would not only display animals but also take an active role in their management and long term survival. To achieve this, Hornaday launched what amounted to a public relations campaign that included letter writing and lectures. The content leaned heavily on civic pride by not so subtly pointing out that, well, all the other great cities of the day had zoological parks.

A grand zoological park would be a victory for conservation and for the bison, but also for New York City’s image.

“We hear so much about New York that is bad, that it is time a better public sentiment were aroused, that we showed to the world what good things New York contains,” said Bird S. Coler, a city comptroller speaking on behalf of Mayor Van Wyck, at the zoo’s opening ceremonies. “It is a pleasant thing–a glorious privilege, in fact–to be a New Yorker!”

Hornaday was able to acquire seven bison for the 1899 opening of the New York Zoological Gardens, which, of course, everybody now calls the Bronx Zoo. A year later, he got eight more bison. Some animals arrived from as far away as Texas and the Midwest. Some arrived from a preserve in New Hampshire.

The Bronx Zoo wasn’t the first zoo in the country. Their bison weren’t even the only ones in the city. Prospect Park had a lone female, and the Central Park menagerie, which was less of a zoo and more of a place for aristocrats to dump an exotic animal, had a few bison too. But, the Bronx Zoo herd was more than just a display piece, it was a longshot nucleus herd intended to save the species from extinction.

To that end, in 1905, Hornaday and others founded the American Bison Society (ABS) in the Bronx Zoo’s lion house. They made Theodore Roosevelt their honorary president and set out to re-establish bison on their former range.

Two years later, in 1907, the Bronx herd contained 35 bison. Running out of room, the zoo stashed 15 of their bison nearby at Van Cortlandt Park for a few months before preparing to ship them out west. At the same time, ABS made an offer to the federal government: set aside some land for a wildlife preserve – a thing that did not really exist at the time – and ABS would provide the bison. The government agreed to the deal and offered Wichita Mountain Wildlife Refuge in Oklahoma, just outside the small town of Cache.

In October of that same year, the 15 bison were shipped by train to Cache. When they arrived on a Friday night, the entire town —all 300 of its residents—came out to greet them at the station, as did a few local members of the Comanche Nation. It was a big deal. These 15 bison were some of the last in the world—and they were here on permanent loan from New York City.

Next, ABS worked to establish and stock the National Bison Range in Montana, followed by the Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge in Nebraska. The group tried to establish a herd in New York State’s Adirondack Mountains only to see their proposal vetoed by Governor Charles Evans Hughes after it had unanimously passed through the state legislature.

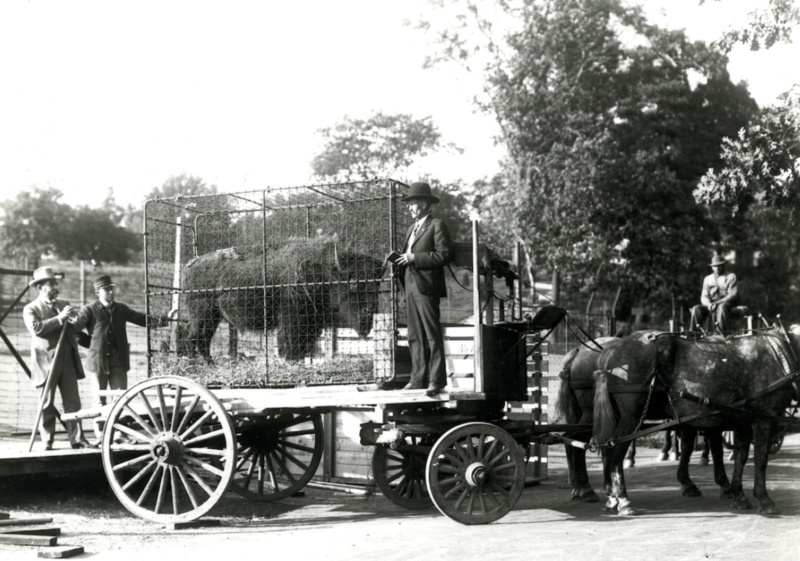

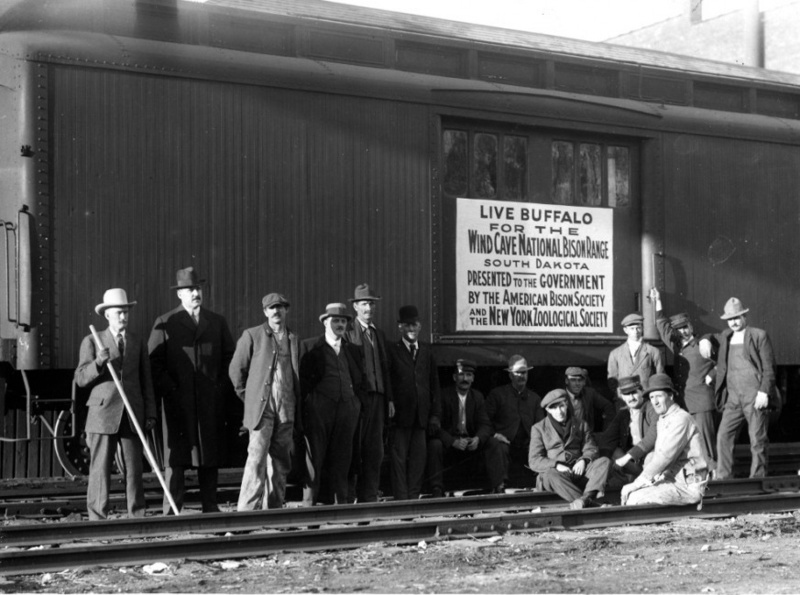

Undeterred, ABS sent another 14 bison from the Bronx in 1913 to Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota, the very same ‘wind cave’ from Lakota mythology. The bison were placed in their own crates and drawn by horse to a waiting train at Fordham Station. From there, they traveled south to the newly opened Grand Central Terminal, where they would change trains before continuing their journey west.

New York City, which has been home to human refugees for centuries, also offered unlikely sanctuary to this once prolific animal, as well as an escape route back to safety. Here was one of the last delegations of bison, not grazing their native plains, but instead riding the New York Central Railroad tracks to Midtown, and on a weekday, with the massive humming city mostly oblivious to this snorting cargo, this monumental roll of the dice unfolding within one of its most storied structures.

Those bison made it safely to Hot Spring, South Dakota later that week and were welcomed with much fanfare, which may seem ironic given how the bison, not to mention the Lakota people, had just recently been removed from these Black Hills. Nonetheless, these 14 of the last bison in the world were given an exemption, and a chance to survive.

“They started that herd up there at the Bronx Zoo with bison they could find, but just with good luck, they ended up coming from all over the country with very diverse genetics,” says Greg Schroeder, Wind Cave National Park’s chief resource manager.

Today, there are around 450 bison in Wind Cave National Park, mostly descended from that original NYC bison herd. (The original herd was augmented by six bison from Yellowstone National Park in 1915.) According to Schroeder, no other bison have come into the park since, though plenty have left.

Over the last thirty-plus years, Wind Cave has shipped more than 1,500 surplus bison to agencies, nonprofits, and tribes throughout the country. Reintroducing as many bison in as many places as possible is good for the general genetic health of the species, but it also helps the environment.

“Even if it’s behind fences, a bison is a huge ecological engineer out there on the landscape. They graze and do other behavior that other animals can’t do,” says Schroeder. “Having them back in as many places as you can, I think is a benefit.”

Since 2020, Wind Cave’s bison, along with all federally managed bison in the country, have been overseen as one meta-population with the goal of avoiding ‘genetic bottlenecks’ and ultimately opening up more land to bison repopulation. Schroeder feels optimistic about the initiative, saying “We’re on the cusp of taking bison management to a whole new level. There is as much synergy and unity in federal bison management as there has ever been.”

One priority target for bison repopulation has been the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. Rosebud was created in 1889, the same year as Hornaday’s bison census, with the passage of the General Allotment Act. This reduced the Great Sioux Reservation by about half, and, in the process, created five small reservations. This federally sanctioned land grab included the spiritually significant Black Hills, where today Mount Rushmore stands nearby scarred into the sacred landscape like a pharaonic profanity.

Rosebud started their herd in 2020. In 2021, another 60 bison arrived from Wind Cave. Through other transfers and natural propagation, Rosebud now has well over 1,000 bison, making theirs the largest tribal-managed herd in the world.

“If the buffalo are healthy, we’ll be healthy. They took care of us for thousands of years, and it’s our turn to take care of them,” says Wizipan Little Elk, a member of the Rosebud Sioux tribe and former CEO of Sicangu Co, which oversees the bison project, who currently serves with the U.S. Department of Interior on Indian Affairs.

The Rosebud bison project is called Wolakota, which translates to peace, balance, and coming together. Little Elk suggests that once the herd is fully stocked, they can harvest around 300-400 excess animals a year sustainably. This could mean jobs for a place with 80 percent unemployment, and locally sourced protein for an area that struggles with food security. However, this will not be a cattle operation applied to bison. There also won’t be a slaughterhouse.

“When we harvest, it’s got to be in the field, and we have to pray with the animals,” says Little Elk. “We have to do this in a way that’s respectful and allows them to be buffalo.”

Though the bison is no longer endangered, the species still faces many challenges. Opening up more land to bison repopulation will help. It’s going to take a lot more work, but none of this would be possible without New York City’s contribution from over a century ago.

The Wildlife Conservation Society had planned to commemorate its 125th anniversary in 2020 with a year of celebrations, which was to include a herd of life-sized model bison that would “‘graze”’ Manhattan’s Times Square, and other iconic locations. But, like a lot of things that year, it was postponed.

Instead of roaming Midtown, the faux herd sits in a storage locker in the outer boroughs, a dust-collecting relic from when we were unable to celebrate the saving of one species without risking the wellbeing of our own. But even if those public tributes never happened, thankfully the legacy of one of New York City’s greatest gifts to the world continues to rumble across the plains.

Next, check out 15 of NYC’s Most Famous Animals