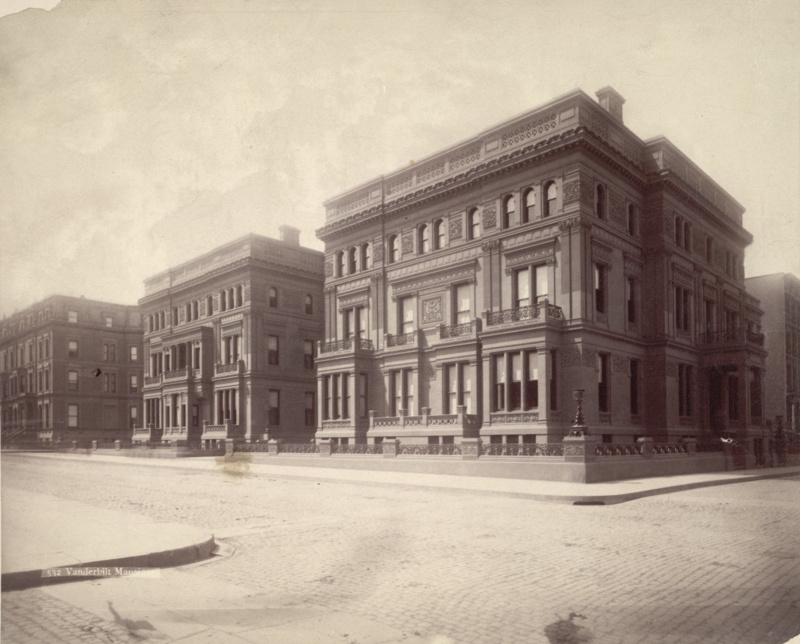

In his opening statement over the dispute of railroad tycoon “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt’s will, attorney Scott Lord proclaimed that Vanderbilt was “a believer in spiritualism” and “clairvoyance and was governed by its revelations.” Lord argued that these beliefs, among other “impairments,” rendered Vanderbilt susceptible to undue influence towards the end of his life while drafting his will. The will allocated the majority of Vanderbilt’s massive fortune to his eldest son, William Henry Vanderbilt, with comparatively modest sums going to the rest of the heirs. The claims of supernatural intervention brought the name of a well-known 19th-century fortune teller, Madame Morrow, into the contentious court battle between William and his siblings.

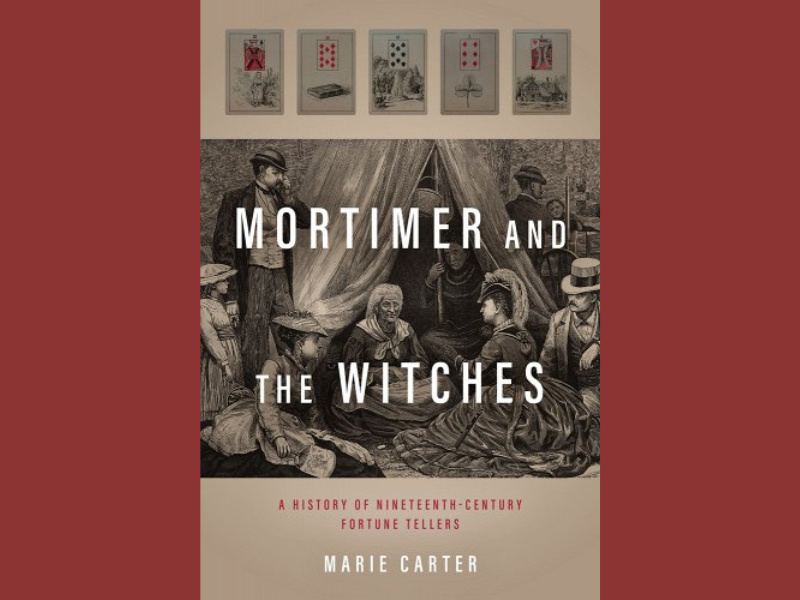

Learn more about Madame Morrow, her contemporaries, and Q.K. Philander Doesticks, P.B (aka Mortimer Thomson, the Bohemian journalist who sought to debunk them), during our live, virtual book launch for Mortimer and the Witches with author Marie Carter! This talk is free for Untapped New York Insiders. Not an Insider yet? Become a member today and use code JOINUS for your first month free.

Madame Morrow began advertising her psychic services in local New York City newspapers in the winter of 1854. An 1876 advertisement from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle declares that she “will tell of past, present and future, describes absent friends, lost property, and treats diseases of every nature.”

She dispensed her otherworldly knowledge from a handful of different locations throughout her life. Madame Morrow lived at 76 Broome Street, 46 Norfolk Street, 184 Ludlow Street, and 808 Myrtle Ave in Brooklyn, among other addresses. We know about some of these locations thanks to her arrest records.

An 1819 New York State statute outlawed the practice of fortune-telling, a practice that remains illegal to this day. This law put Madame Morrow and many other working-class women who shared her trade under constant threat of arrest. Records show that authorities arrested Morrow a handful of times in both New York and Philadelphia. However, these encounters with the law never deterred her. Newspaper advertisements for her special powers quickly followed sensationalized reports of her arrests.

Morrow had little choice but to continue in her work. While she reported that her income was from dressmaking, fortune-telling provided much more money than dressmaking ever could. Women of the 19th century had very few options to pursue in order to financially support themselves, and fortune-telling, despite its risks, was appealing.

Madame Morrow was well known for her psychic abilities, especially among the young ladies of New York City who sought to find out who they would marry. Morrow must have made an exception in seeing Vanderbilt, as she typically didn’t allow men into her salon. In Mortimer and The Witches, Carter relates the story of how Thomson dressed up in women’s clothing to sit for a reading.

At the Vanderbilt court proceedings, multiple witnesses took the stand to describe conversations with the Commodore about spiritualism, mediumship, and fortune-telling. In October 1878, Helen C. Stille took the stand and told the rapt audience how she accompanied Vanderbilt on a visit to Madame Morrow’s. Vanderbilt told Stille that Morrow “had told him strange things and she was a wonderful woman,” as reported by The New-York Tribune.

When Marie Antoinette Pollard testified, she claimed that Vanderbilt told her he often got messages from spirits. These messages were received through mediums, which cost him a great deal of money. One message that came through told Vanderbilt to leave all his money to one child. Another witness, Mrs. Lillian Stoddard, the widow of Vanderbilt’s medical clairvoyant Dr. Charles Stoddard, claimed that these spirit messages were manipulated. Lillian told the court that William, Vanderbilt’s son, instructed her husband to deliver a very specific message to the Commodore. The message was to come from Vanderbilt’s dead wife and advise him to make William his successor.

Vanderbilt’s belief in the spirit world was just one angle lawyers used to question his mental state and therefore the validity of his will. By 1879, William Vanderbilt had heard enough. As explained in Fortune’s Children: The Fall of the House of Vanderbilt, William decided to settle with his siblings. He gave them $200,000 cash and a $400,000 trust fund. This was a paltry sum compared to the $95 million William had inherited.

Madame Morrow herself was never called to the stand. She likely died around the time of the trial. Though there are no official records of her death, her legacy is remembered through a deck of fortune-telling cards that bear her name. This specialty deck first appeared in 1867 and remains in circulation today.

Uncover more stories of New York City’s 19th-century fortune tellers and the journalist who tried to debunk them in our upcoming talk with author, New York City tour guide, and Untapped New York Insider Marie Carter!

Next, check out Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Birthplace is Now a Chinese Take-Out