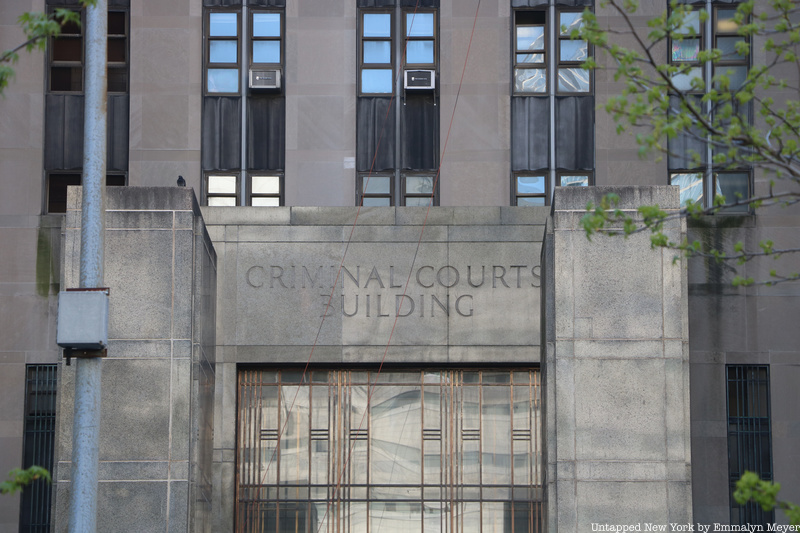

The crowds outside Donald Trump’s New York trial were looking particularly thin this past week. If you’re planning to witness this unhistoric moment from inside the courthouse, now is your chance. Despite Trump’s calls for protesters and his claim that thousands of supporters were turned away from the Criminal Courthouse in Lower Manhattan—where he is currently on trial for 34 felony counts related to falsifying business records, there were a mere handful of supporters in the designated protest area when Untapped New York visited the courthouse on the morning of April 26th. Likewise, major news outlets like The New York Times and CNN reported that no such crowds existed.

As assumed by the First Amendment, the public has a right to attend most court proceedings in New York state courts. While the First Amendment doesn’t explicitly mention the right of access, the Supreme Court has stated that the right to attend court proceedings is implicit in freedom of speech and serves an important function in a democratic society.

In New York, courts are generally divided by the nature of their case: civil or criminal. It is understood that witnessing civil cases (while sometimes less exciting) prompts fewer questions from court clerks. Criminal proceedings (a little more flashy) are also open to public viewing, with some exceptions such as juvenile court to protect the privacy of a minor.

If you are interested in attending a court proceeding, do your homework beforehand! I recommend checking out the New York judiciary’s website to find your local courthouse and any upcoming cases. Different boroughs may have different rules, but the general process is the same.

Upon arriving at the courthouse, locate the clerk’s desk and ask for a copy of the trial schedule for the day (this is usually available online as well). It should list the judge assigned to the case, the defendant, the charge, and the courtroom. Don’t be afraid to ask court officers for directions to a courtroom – they get those questions all the time!

Another useful tidbit, phones and decries are generally not allowed inside and can get you kicked out of the courtroom. If you’re keen on taking notes, bring a pen and notepad.

I recently tested out this Constitutional right at the Queens County Supreme Court. As I sat outside courtroom 122, bouncing my leg on the unforgiving wooden bench, I felt like I was on trial.

The Queens County Supreme Court opens at 9 a.m., but at 8:30 a.m. a long line had already started to form outside the building. As I walked up to the court officer who was directing foot traffic, she looked me up and down. Her glance stopped briefly on my Starbucks latte before asking, “Jury notice? Get on the line.” I informed her that I was a student journalist hoping to observe a court proceeding for a medical malpractice case happening at 9:30 a.m. that day. She nodded and affirmed, “Public is allowed to witness court proceedings, just wait over there.” I sat next to a shivering old woman in a wheelchair. At 9 a.m. sharp, the court officer ushered us all inside.

Although I knew not to bring my pepper spray that normally hangs on my lanyard, I didn’t expect to be stopped at the metal detector for my travel-size Glossier perfume. I frantically dug through the contents of my bag to locate the small metal tube before finding my way to the clerk’s office.

“You’re a law student?” asked the clerk from behind the plexiglass.

“A student journalist actually,” I replied.

The clerk dialed a number and spoke into the phone, “Yeah, there’s a law student here who wants to sit in on a case.”

One long, painfully redundant conversation later, I was told I wouldn’t be allowed to observe the medical malpractice case I had researched the night before. Although I knew the public has every right to sit in on court proceedings, I felt it was best not to argue with the clerk, who was already getting aggravated by my existence. Instead, I was instructed to wait outside courtroom 122 and someone (no idea who) would let me in to observe a different case, just as long as the judge signed off.

And so I waited on the bench outside the courtroom for what seemed like forever but was actually an hour and fifteen minutes. In that time, I saw a court officer escort eight jurors into the courtroom, I saw the judge enter her chambers, and the attorneys prep their clients.

Fearful that I was missing the action, I finally worked up the nerve to knock on the courtroom door. As I approached the door, a woman holding a stack of papers flung it wide open, “You’re the law student, right? I almost forgot about you.”

As I walked in, the plaintiff’s attorney was yelling at the judge who calmly replied, “Counsel, you will have a level of respect for the court or we will not continue.”

I sat behind his clients who put their faces in their hands, maybe to shield themselves from the outburst.

It was clear at that moment, and through many following moments, that this wasn’t the attorney’s first offense. In fact, the next two hours were spent waiting for him to organize his evidentiary packets. Not only was he short on documents, forcing the defense to share with the judge, but he had also included a police report without redacting certain names. After being instructed to do so, the attorney exasperatedly asked, “You’re not going to help?” to which the judge replied it was “not the court’s responsibility” to prepare his materials.

The attorney left the courtroom multiple times, continuously spoke over the judge, and couldn’t seem to keep the back of his shirt tucked in.

When we broke for lunch, the opening statements still hadn’t been read.

I decided not to stray too far and wandered into a dumpling spot opposite the courthouse. As I sat down to eat, one of the defense attorneys walked up to my table. We got to know each other over fried dumplings and lo mein and I asked him if every trial is that exciting.

“Kid, you don’t see that every day.”

Next, check out Donald J. Trump Park’s Abandoned Gilded Age Estate and Inside the New York County Supreme Courthouse