When you think of some of the most iconic photographs ever taken–Napalm Girl by Nick Ut, the portrait of Che Guevara by Alberto Korda, the famous V-J Day kiss in Times Square by Alfred Eisenstadt, or Falling Soldier by Robert Capa, just to name a few–chances are they were taken by a Leica camera. Today Leica remains just as prestigious, but is a name more known among professional photographers than the masses. Leica Camera AG has been looking to change that, first with the steady stream of Leica store openings around the world, from Los Angeles to Taipei.

In late May, Leica celebrated its 100th Anniversary with the launch of a brand new headquarters and factory in Wetzler, Germany, where the company began.

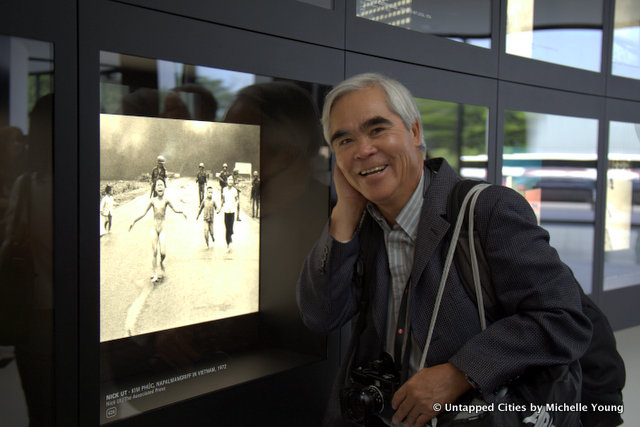

Nick Ut in front of his iconic Napalm Girl photograph. He tells us he’s still friends with the girl in the photograph, who now lives in Canada.

Nick Ut in front of his iconic Napalm Girl photograph. He tells us he’s still friends with the girl in the photograph, who now lives in Canada.

Untapped Cities got a behind-the-scenes tour of the new factory the day before the anniversary celebration. Akin to office complexes we’ve written about before, like the Google office in Mountain View, the Leica headquarters at Leitz-Park caught our eye because inside and out, the design is an architectural reflection of the company’s ethos.

Inside the Leica Store at Leitz-Park

Inside the Leica Store at Leitz-Park

It was in Wetzlar, Germany that Leica engineer Oskar Barnack created and built the first photo camera made for 35 millimeter cinema film. Before this, photography was still limited by long exposure times on big glass plates using wooden box cameras on tripods. Leica has always been a scientific company to its core, as reflected by the large business it still does in high-end microscopes for research labs. The underlying question of the exploration into cameras for Leica was how to produce “big images from small negatives.

Small negatives also meant smaller cameras, and the Leica was quickly adopted by the avant-garde artists of the era like Russian Constructivist Alexander Rodchenko and Surrealist André Breton. These cameras weren’t carried at waist level either but at eye level, an important technical development as the art world began to explore the link between subconscious and reality.

The Leica could fit in your pocket and could expose images almost instantaneously. Its discreet nature lent itself to creative photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson who walked the street of Paris like a flâneur, and to photojournalists like Robert Capa who took his Leica to document the Spanish Civil War. With a 35-50 mm lens, the Leica camera wasn’t built for long shots but rather for capturing the human condition. The Leica camera has always been associated with capturing deep, human moments, and was a key figure in the history of street photography, embodied in Bruce Davidson‘s images of street gangs in New York City.

For the 100th Anniversary of Leica, the company is digging heavily back into its history and legacy while building anew. It is also being very upfront with its more recent challenges, admitting in a Special Edition of Leica Fotografie International magazine that “there have been times in which this legacy had been more of a burden than an asset. It is only ten years ago that Leica stood on the edge of ruin.” Leica was rescued from dire financial straits by photography aficionado and businessman Dr. Andreas Kaufmann, now the chairman of Leica’s Supervisory board and a majority shareholder in the company, and was brought into a new era.

Perhaps most important in the new Leica headquarters at Leitz-Park is that it has been built with visitors in mind. Chairman of the Board Alfred Schopf says, “We are expecting thousands of visitors every year, including from abroad.” As such, architects Martin Gruber and Helmut-Kleine Kranenberg (responsible also for the Office of the President in Berlin) have carefully curated an experiential path through the public spaces.

The floor of the lobby is made of terrazzo

The floor of the lobby is made of terrazzo

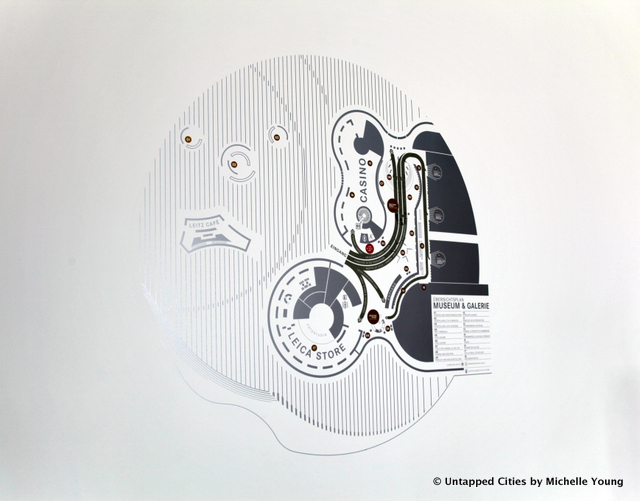

The entire complex includes a museum, exhibition hall, flagship store, a photo studio, factory and offices. The first and most obvious design referent to Leica’s past and present is its exterior, shaped like a lens (or perhaps even like 35 mm roll of film when the building is taken as a whole). That design mantra extends to the floor to ceiling glass facade, custom-made to be convex and concave where necessary.

While it might appear that architectural Modernism hasn’t had an impact on the exterior of this literally-shaped building, the building does takes advantage of new technological advances. The concrete is subtly imbued with color to look like stone and the materials allow for the building to be green: 22° C warm water runs through pipes in the walls, ceilings, floors, and columns cooling the building in the summer and heating it in the winter. This, combined with geothermal tubes under the parking lot and photovoltaic panels on the roof means that the complex can generate most of its own power sustainably.

22° C water runs through the walls, cooling down the building in the summer

22° C water runs through the walls, cooling down the building in the summer

Only a few colors appear on the interior of the building–black, white and steel. While adhering to such colors can lead to empty Modernism, it works well in Leitz-Park because it feels done as a reflection of the precision engineering that’s at the core of Leica. In fact, the stark color scheme not only works for hosting exhibitions in the entrance hall, it also makes the transition between gallery and the factory rather seamless.

The exhibition hall currently features the “10×10 Exhibition” showcasing the work of 10 up-and-coming photographers like Evgenia Arbugaeva and her haunting photos from a meteorological station in the Arctic Circle.

Photos of Hodovarikha Meterological Station by Evgenia Arbugaeva

Also on display in the main gallery is “36 Aus 100,” a selection of 36 iconic photos from the 100 years of Leica, as well as displays of historical Leica camera models used by the photographers.

Image via LFI “Leitz-Park”

Image via LFI “Leitz-Park”

The first Leica ever delivered to a customer, no. 126. Prior versions were part of the pilot series.

The first Leica ever delivered to a customer, no. 126. Prior versions were part of the pilot series.

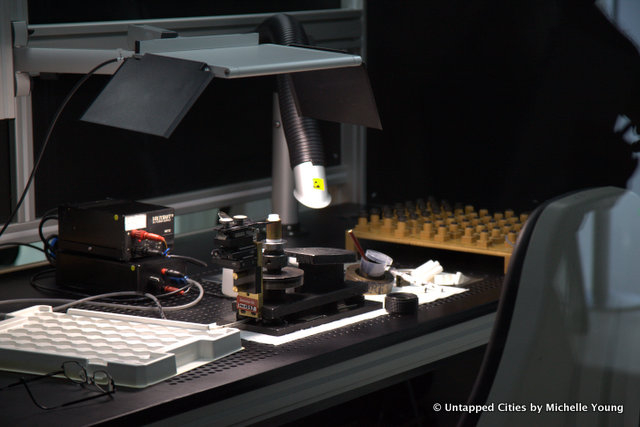

Around the corner from this museum-like space is the entrance to a long, cinematic hallway which gives the visitor a glimpse into the factory floor. Because the rooms are dust-free, via an elaborate pressurized, air filtering system, visitors can only look in to the work being done. Each window has a touch screen which provides additional information about the process of making Leica cameras, which are all hand-made in Germany.

It’s a painstaking process with 8 assembly lines producing just 500 cameras per day, mixing high tech processes with a tradition of hand precision. It takes several months to train technicians, so Leica has not been able to be as flexible to the demands of supply and demand as they would like–but they’re working on it with mentoring programs between Portugal, where one of the Leica lens factories is located and Germany.

The areas shown thus far are designed to take visitors on a controlled and programmed path through Leica’s history and current production. But the true test of how far-reaching a company’s beliefs extend is whether its brand values are reflected in the areas that the company doesn’t necessarily expect the public to see. Leica has always been about attention to detail, scientific precision and design, and this mantra made its way even to places like bathrooms and stairwells.

When you step into this stairwell, it feels like you’ve entered into a Guggenheim Museum-esque echo chamber, sealed off from the din of the Leica cafe and exhibition hall. Look up and you’ll feel yourself drawn to the natural light above:

From the top, you can see echoes of camera lens design–nothing is quite circular but rather combinations of convex and concave lines:

The black and white theme continues into the bathroom where the entire floor (stalls included) are painted in a thick black:

The reverse theme applies to the locker rooms:

Another beautiful staircase in the customer care area of the complex:

The studio, which is part of the Leica flagship store, is large enough to fit a car and motorcycle inside for a photo shoot. The store and studio will also be a teaching space for the Leica Academy, historically the oldest modern photography school in Germany.

Leica is also getting into the business of printing, in partnership with Whitewall Photolab. At the Leica headquarters and in retail locations around the world, you’ll be able to buy prints from famous photographers or get advice on the best paper and technique to print your own.

But Leica has also not shied away from the digital revolution in photography, and has an ongoing partnership with Instagram. Leica believes that the democratization of photography through the smartphone will only bring new enthusiasts towards the high-end products Leica is offering .

The cafeteria, which Leica calls the “Casino” comes with a built-in bar with beers on tap:

Upon your exit, stop by the coffee house located on the exterior plaza, an idea Dr. Kaufmann had for employees that also serves to activate the large public space. In many ways, this is what Leica hopes to achieve on a larger scale with its headquarters in Wetzlar, establishing a new type of urban complex that can reactivate the industrial district of the city and welcome business and leisure visitors alike.

It’s clear that architects Martin Gruber and Helmut Kleine-Kraneburg served as more than just design consultants. In fact, they worked as general planners as well as architects on Leitz-Park. Value and modernity was just as important as the visual aesthetic, and with their active involvement they were able to focus on quality to the last detail. Says Kleine-Kraneburg, “It’s the only way to ensure best value. We don’t need opulence or formal obtrusiveness to acheive this, but rather a client who is willing to walk the same path with us.”

Get in touch with the author @untappedmich. For more information on the latest line of Leica products, head to the official website.