The Harlem Hellfighters returning to New York City. Photo from National Archives, created by the War Department.

The Harlem Hellfighters returning to New York City. Photo from National Archives, created by the War Department.

When New York’s all-black 369th Infantry Regiment set off to fight in World War I, they were men without rights at home or in the military, sent on a mission to “make the world safe for democracy.” One could have forgiven them for serving with cynicism. Instead, they were some of the most decorated and accomplished American soldiers of the war, and on February 17, 1919, they finally got a parade to celebrate their heroism.

Things didn’t get off to a great start. The 369th, assembled in a Harlem ballroom, was sent to train in Spartanburg, South Carolina. At the time, an all-black regiment had recently been sent to Texas, where a lynching had led to a deadly confrontation between locals and soldiers, ending with thirteen black soldiers hung for mutiny. The 369th, warned to turn the other cheek no matter the circumstance, suffered countless humiliations in Spartanburg, including being denied uniforms or weapons. They cleverly acquired rifles by posing as a white private rifle club, to whom the government had no problem shipping guns. The indignities continued on the way to Europe. After being denied a spot in the farewell parade, their leaky ship had to turn back – and in Europe, where they were assigned to manual labor. They got their break soon enough.

The 369th Regiment was the first New York regiment to parade as veterans of Great War. Photo from National Archives, created by the War Department.

The 369th Regiment was the first New York regiment to parade as veterans of Great War. Photo from National Archives, created by the War Department.

Following the Russian withdrawal from the war in 1917, the French desperately needed help on the Western Front, and welcomed the all-black regiment with open arms. They loved the music (the leaders of the 369th included James Reese Europe, an early figure in the New York City jazz movement. The combat bravery of the all-black regiment (Henry Johnson became the first American to receive the French Cross of War), treating them as equals until a memo from the U.S. military told them to cool it.

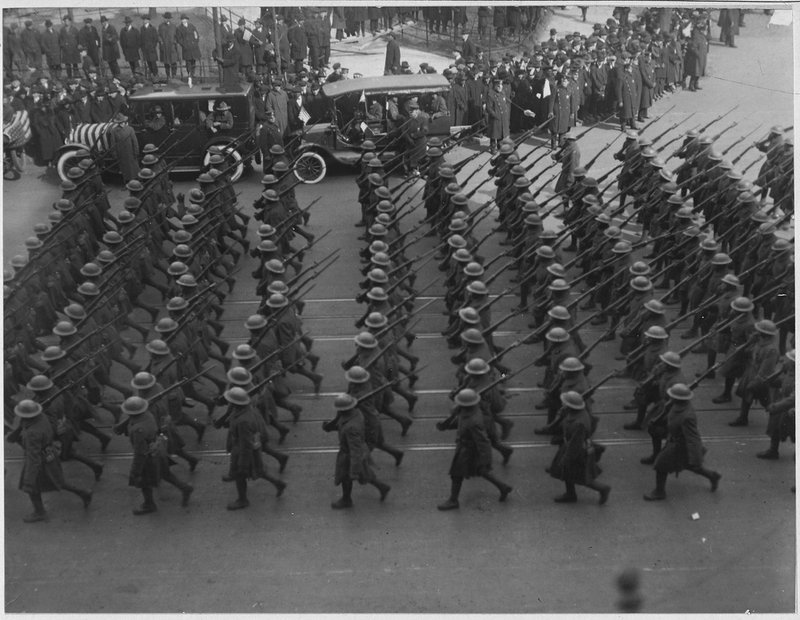

369th Infantry marching on Fifth Avenue, New York City. Photo from National Archives, created by the War Department.

369th Infantry marching on Fifth Avenue, New York City. Photo from National Archives, created by the War Department.

Their reputation went global when Irvin Cobb, a white southern journalist wrote of their exploits, “If ever proof was needed, which it is not, that the color of a man’s skin has nothing to do with the color of his soul, this twain then and there offered it in abundance.” During these epic months on the front lines, the 369th Regiment called themselves “the Black Rattlers” and the French called them “the men of bronze,” but it was the German enemy that gave the nickname that stuck: “the Harlem Hellfighters.”

None of that glory mitigates the horrors of war. The trench warfare of World War I, coupled with horrifying new weapons like machine guns and chemical bombs, made every day a gruesome slog of mud, rats and incoming fire. But the Hellfighters stuck with it to the end, even volunteering for a dangerous final mission in the last hours of the war. Many Hellfighters were killed, others returned home injured or suffering from PTSD. All suffered discrimination in the democracy they had fought for. But they got their moment to shine.

On February 17, 1919, a parade headlined by 1,200 Hellfighters and the Hellfighters band, led by James Reese Europe, marched up Fifth Avenue from downtown all the way through Harlem.

Europe was killed later that year by his own drummer, but not before recording “On Patrol in No Man’s Land,” a groundbreaking jazz song with machine gun sound effects and provocative lyrics about life on the front lines.

Harlem historian Jonathan Gill suggests that the Hellfighters parade might be “a candidate for the start of the Harlem Renaissance.” Unfortunately, the Hellfighters’ valor alone couldn’t break segregation in the military, which lasted until President Truman’s Executive Order in 1948, nor was equality on the battlefield enough to convince white America of equality at home. But for one fine afternoon, the Harlem Hellfighters could finally bask in the adulation and respect they so richly deserved.

Fun fact: Author Max Brooks, was a Hellfighters fan for years writing the graphic novel “The Harlem Hellfighters” before publishing World War Z.

Read more from Today in NYC History on Untapped Cities and on janos.nyc