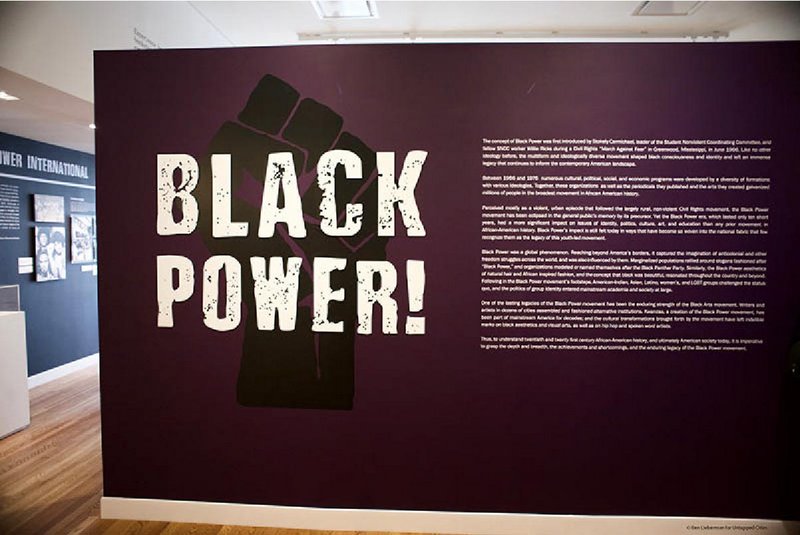

During the Harlem Renaissance, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture became a hub for African-American writers, artists, intellectuals, and activists. As part of Black History Month, and a year-long examination into the 50th anniversary of the Black Power Movement, the Schomburg Center unveiled a powerful new exhibit entitled Black Power! The exhibit is on view in the newly renovated main exhibition hall located in the original Carnegie library, which was once the home to the American Negro Theater, housed a WPA Writers Project, and where the likes of W.E.B. DuBois, Franz Boas and Carl Van Doren held weekly lectures.

The exhibit is located in the newly renovated space within the original Carnegie Library on 135th Street

The exhibit is located in the newly renovated space within the original Carnegie Library on 135th Street

Black Power!, curated by Dr. Sylviane A. Diouf, will take the viewer back in time through photos, videos, and written material, to the original concept of the Black Power Movement, beginning in 1966, as put forth by Stokely Carmichael and Willie Ricks, following the Civil Rights Movement. Exhibits explore the growth of the Movement inside the prison system, and grassroots organizing in poor communities throughout the country, and beyond.

Specific exhibit areas showcase Organizations, Political Prisoners, Coalitions, Educations, The Look & Popular Culture, Spreading the Word, Black Power International, the Black Arts Movement and more

Specific exhibit areas showcase Organizations, Political Prisoners, Coalitions, Educations, The Look & Popular Culture, Spreading the Word, Black Power International, the Black Arts Movement and more

Sonia Sanchez and Queen Mother Moore, Photograph by Margaret Randall, 1988

Sonia Sanchez and Queen Mother Moore, Photograph by Margaret Randall, 1988

Expression through the arts played a major role, as the Black Arts Movement (BAM) was used as a way to express oppression and poverty. Arts took many forms – murals, music, theater, and poetry, which is of particular interest to Kevin Young, the new Director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, since he served as Curator of the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library from 2005 to 2016. Through the arts, the Black Power Movement was able to spread the word in a nonviolent way, reaching an audience that transcended class and ethnic lines.

Kevin Young, the new Director, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

Kevin Young, the new Director, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

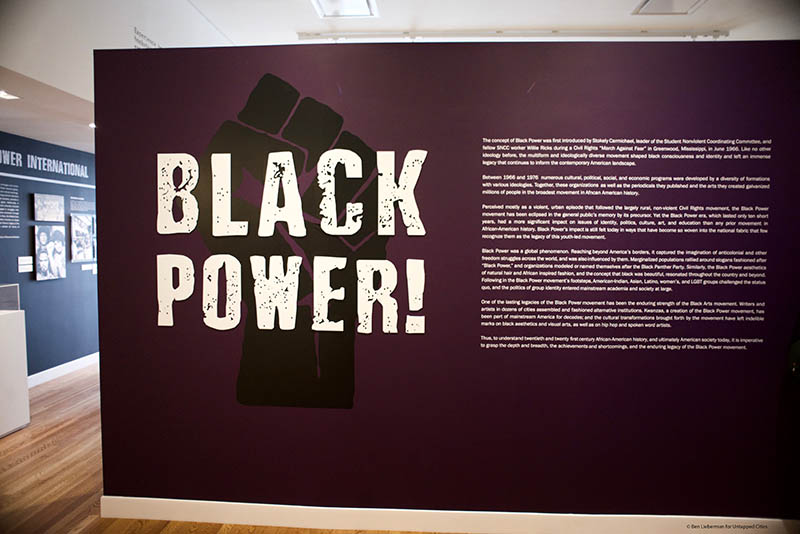

Pictured above is the Liberation Bookstore, which was opened in Harlem in 1967 by Una Malzac

Pictured above is the Liberation Bookstore, which was opened in Harlem in 1967 by Una Malzac

In addition to the arts, artists and activists published written texts by way of periodicals, newspapers, books, publishing companies and bookstores as a way of providing historical knowledge and cultural pride. The birth of Panther Schools took hold. A new consciousness emerged focusing on a Black identity in fashion, arts and sports, where athletes were not just winning medals, but also affirming their identities. Muhammad Ali spoke frequently about the “white sports industrial complex,” and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar refused to play on the Men’s Olympic Basketball Team to protest inequality and racism.

Black bookstores, in particular, became social meeting centers for authors, militants, and visiting activists. Not far from the Schomburg Center was the Liberation Bookstore, which was opened in 1967 by Una Malzac on the corner of Lenox Avenue and 131st Street. While Liberation Bookstore has been gone for many years, Revolution Books moved from Chelsea to Harlem a few years ago, just a block away on 132nd Street and Lenox Avenue, continuing the history of keeping political issues in the forefront.

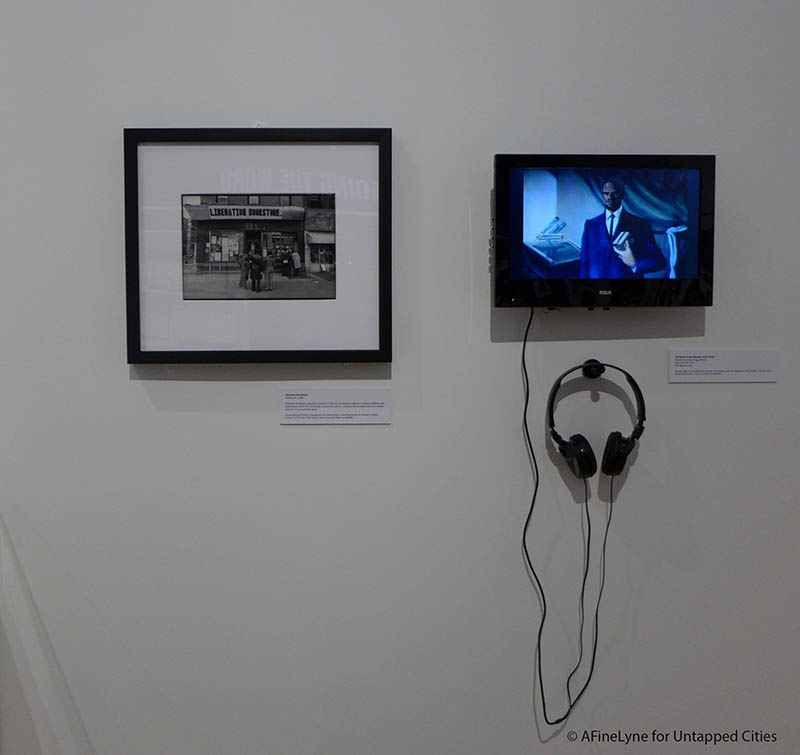

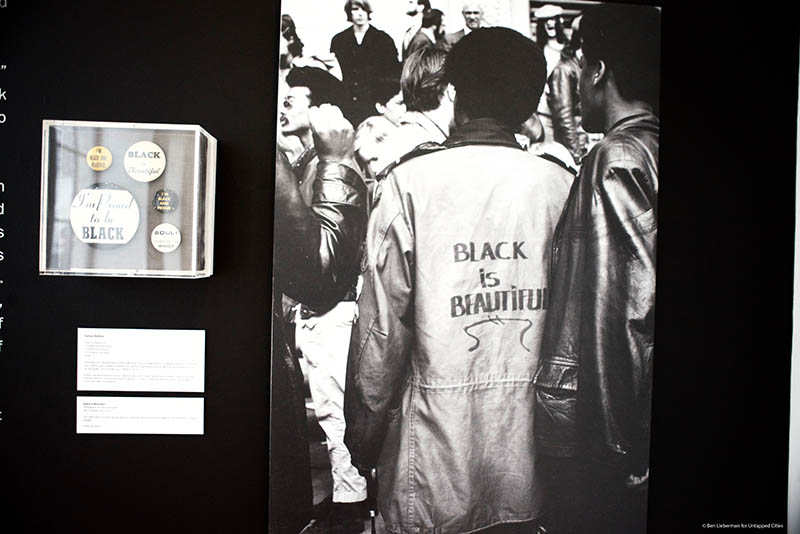

Other oppressed groups of marginalized people identified with, and aligned with, the Movement, which went on to transcended race. It was the time of the Cold War and Viet Nam. Black Power became more than a slogan, and the slogan Black is Beautiful, was a genuine feeling of racial and cultural pride, as the aesthetics of natural hair and African-inspired fashion took hold.

All around the room, above the glass exhibition cases, and wall exhibits, are quotes taken from old FBI notes on the Movement, such as “The Black Panther Party, without question, represents the greatest threat to internal security of the country.” J. Edgar Hoover, June 15, 1969, and “Experience has shown that Afro-American cultural-type bookstores often serve as a meeting place for black extremists and as a nucleus for their activities.” FBI, October 22, 1968.

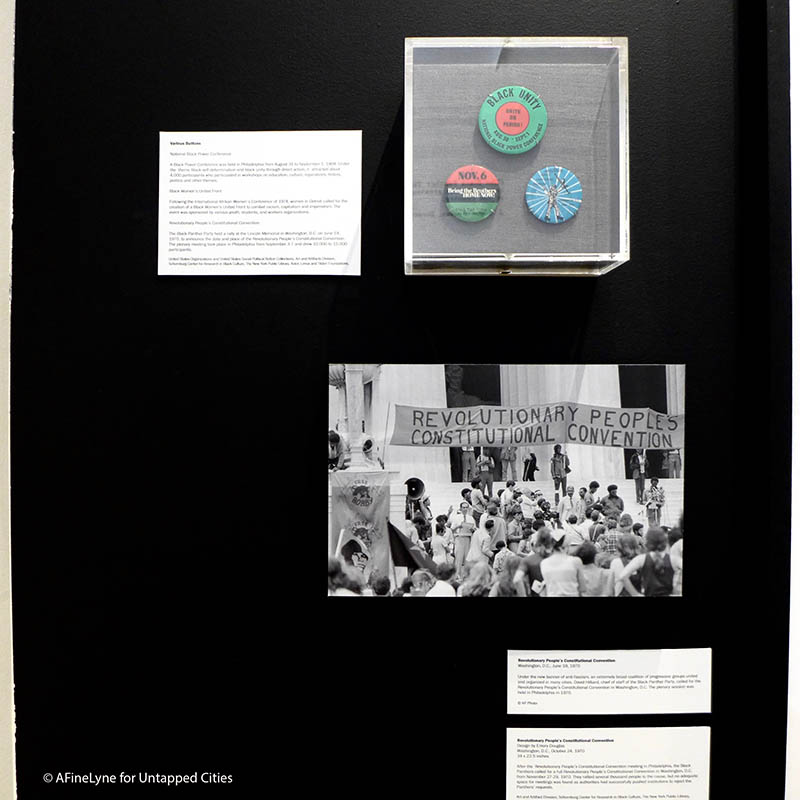

Buttons from the National Black Power Conference held in Philadelphia in 1968; below, Newark Black Power Conference, 1967

Buttons from the National Black Power Conference held in Philadelphia in 1968; below, Newark Black Power Conference, 1967

Black Power! exhibits an in-depth history and achievements of the Black Power Movement, an understanding of how the Movement reached this point in time, gives thought to, and opens dialogue on where the Movement might be headed.

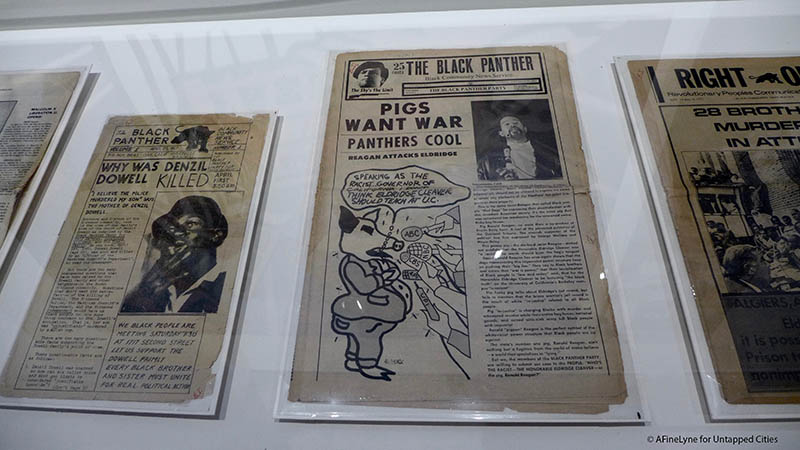

Original Black Panther Coalition Flyer & First Issue of The Black Panther

Original Black Panther Coalition Flyer & First Issue of The Black Panther

Photographs of Eldridge Cleaver, Huey Newton, James Baldwin, and Black Panther Party co-founder and chairman, Bobby Seale, are prominently displayed, alongside original buttons, flyers, and pamphlets. The first issue of the publication The Black Panther, dated April 25, 1967 and published by Bobby Seale and Elbert Howard is on view (above photo).

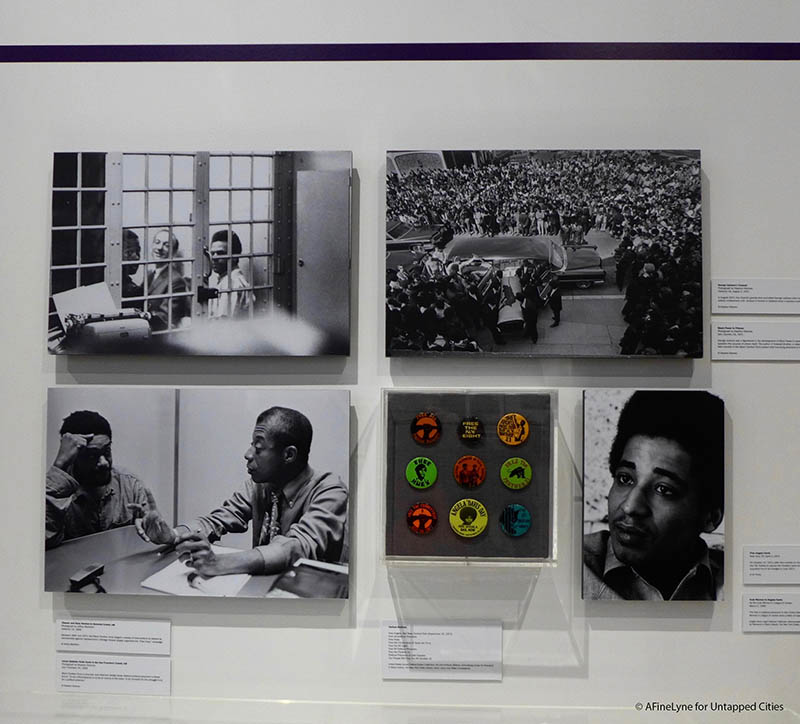

Top left, Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton in Alameda County Jail, 1968; below left, James Baldwin visits Bobby Seale in the San Francisco Jail, 1969; top right, funeral of George Jackson, Oakland, California in 1971, who was shot and killed by guards at San Quentin; Various buttons from the U.S. Social Political Button Collection, Art and Artifacts Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

The Panther schools were formed for the purpose of addressing the needs of the underserved populations. Launched in 1969, they were referred to as “survival programs,” with the Oakland Community School being the longest standing program of the Black Panther Party. These schools were open to children of every ethnicity.

Recently unveiled Media Gallery, which includes Schomburg Center history and timeline, online exhibits, Google Earth, an interactive collections experience, and Blaxploitation films from Black Power!

Recently unveiled Media Gallery, which includes Schomburg Center history and timeline, online exhibits, Google Earth, an interactive collections experience, and Blaxploitation films from Black Power!

Kevin Young, Director of the Schomburg Center with Savona Bailey-McClain, Director of the West Harlem Art Fund in the new Media Gallery

Kevin Young, Director of the Schomburg Center with Savona Bailey-McClain, Director of the West Harlem Art Fund in the new Media Gallery

Black Power! is part of a year-long exploration into the 50th Anniversary of the Black Power Movement. Black Power 50 includes a two-part digital exhibition in partnership with Google Cultural Institute, and the Schomburg’s new exhibition catalog. Black Power 50, along with related programming, Black Power! is curated by Sylviane Diof, Director of the La Director of the Lapidus Center for the Historical Analysis of Transatlantic Slavery, and Director of the Schomburg-Mellon Humanities Institute. Isissa Komada-John is Exhibitions Manager at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. The exhibit Black Power! will be on view through March 2018, located at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, part of the New York Public Library, 515 Malcolm-X Boulevard (Lenox Avenue), on the corner of 135th Street, in front of the #2/#3 subway stop. Expect to see Posters from the Black Power Movement opening in May.

And finally, here is some background about the Black Power! exhibition space. In 1901, Andrew Carnegie donated $5,200,000 (which is the equivalent of $149,697,600 today) to construct 65 branch libraries in New York City, known as the Carnegie Libraries. The Schomburg Center Landmark Building branch, located at 103 West 135th Street (below), opened in 1905 with 10,000 books. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978, and a Designated New York City Landmark in 1981. The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture now consists of three connected buildings which include the Schomburg Building, the Langston Hughes Building, and the Landmark Building.

When leaving the Schomburg Center, check out the WPA mural directly across the street, on the facade of Harlem Hospital. Explore more ways to celebrate Black History Month, and New York at its Core at The Museum of the City of New York. You can contact the author at AFineLyne.