Museums do more than just teach us about things. At their best, museums provide us a way to think critically, a way to see the world, a way to move through our towns and cities and nations and global communities. Attempting this task is “The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin,” a new exhibit at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan.

As Benjamin chronicles, the Parisian arcades—covered markets first erected in the 1820s and 1830s—were made out of the same iron as the railroads that crisscrossed France by the mid-nineteenth century. As new, modern phenomena, both the arcades and the railroads were marvels that brought together diverse people and diverse goods from all over the country and all over the world.

Through the railroads, wine could be delivered to Paris from Bourdeaux and Camembert from Normandie. Likewise, raw materials could be more easily imported from Algeria and Southeast Asia to be sold in these glass galleries. The regions of the French empire were brought together in a new global community, but just as much as they brought together things, the arcades brought together people from all of these places and territories beyond. Like the railroad that bridged gaps between the South and the North, between France and Asia, the arcade created a new sense of time and place.

Paris Arcade. Viollet / The Image Works Copyright Image provided by Musée Carnavalet / Roger-Viollet / The Image Works

Paris Arcade. Viollet / The Image Works Copyright Image provided by Musée Carnavalet / Roger-Viollet / The Image Works

In his magnum opus, The Arcades Project which was begun in the 1930s but never finished, Walter Benjamin took the by then decaying Paris arcades and used them to illustrate and illuminate the conditions of urban life at the dawn—and twilight—of the modern age. The Arcades Project is a work that, like the most effective museum exhibits, offers a new way of thinking about the city and about the world as it shows us social relationships in the objects and architecture that surround us daily. Indeed, the crowded arcades were home to the chaos, illogic, and diversity of urban life, representing modernity itself. Their ruins in Paris were and are persistent fragments that remind us how the past stays with us once it is no longer modern.

If, for Benjamin, the arcade was the signature space of modernity, the flaneur was its signature character. The flaneur is the urban denizen who strolls down city streets and Parisian arcades without a destination, walking just to walk, seeing just to see. For the flaneur, the chaotic city is a spectacle unto itself, an experience unto itself, a work of art unto itself.

Nicholas Buffon, Katz’s Delicatessen, 2017, foam, glue, paper, paint, 19 x 33 x 6.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Callicoon Fine Arts, New York.

Nicholas Buffon, Katz’s Delicatessen, 2017, foam, glue, paper, paint, 19 x 33 x 6.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Callicoon Fine Arts, New York.

“The Arcades,” like The Arcades Project, envisions for us the world of the flaneur ambling through the gallery as much as the city. As the museum itself articulates: “Visitors are encouraged to experience the exhibition as a flaneur, one who strolled through the city at leisure, encountering ideas, objects, and characters seemingly by chance and in no particular order.” Modernity persists.

Like Benjamin’s work, the Jewish Museum’s current exhibit offers a portrait of modern life, but it is not so much of Paris, capital of the nineteenth century, as it is of New York, capital of the twentieth. The presence here of Kenneth Goldsmith, whose poetry annotates the exhibit and who wrote his own Benjaminian opus on New York City—dubbing it the capital of the twentieth century—only enhances this feeling. While we should also question the differences between Paris and New York, between the nineteenth century and the twentieth, and between Benjamin and Goldsmith, the parallels are compelling.

Taryn Simon, Folder: Swimming Pools, 2012, archival inkjet print, 47 x 62 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

Taryn Simon, Folder: Swimming Pools, 2012, archival inkjet print, 47 x 62 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

Indeed, when it is most interesting and most successful at drawing analogies between these times and places, the exhibit finds exciting commonalities not just between Paris and New York, but between being a flaneur in the museum, being a flaneur in the city, and being a literary flaneur like Benjamin or Goldsmith. In this way, the exhibit connects Benjamin’s chaotic modernity to Goldsmith’s fragmentary postmodernism through the logic of a museum that itself brings together a Judaic calendar, a Statue of Liberty menorah, and Andy Warhol’s “Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century.”

Yet while the thesis of the exhibit is exciting, the artworks on display are sometimes less so.

Nicholas Buffon’s miniature store fronts are quite charming, and the neon signs of Katz’s Deli and a Lower East Side coffee shop work with the text-heavy exhibit in a way that reminds us that as we stroll through the city we read it both in the sense of interpreting it and in the sense that it is lettered.

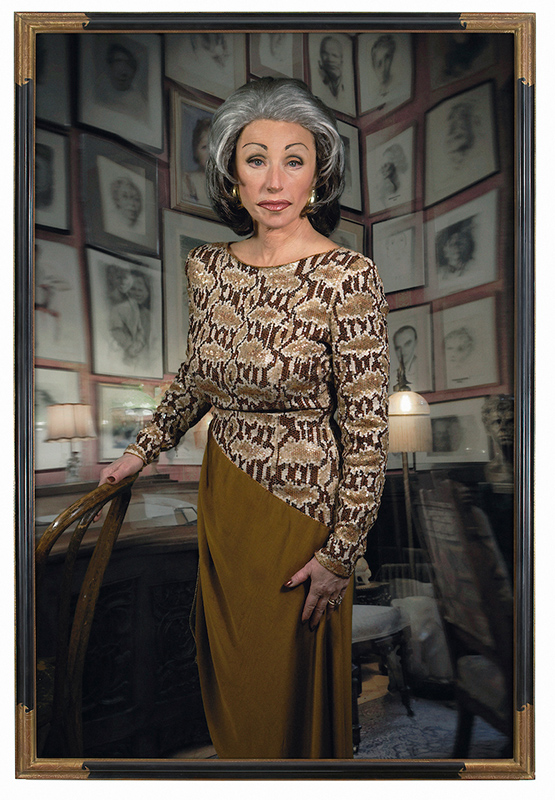

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #474, 2008, chromogenic print, 90.8 x 60 inches. Collection of Cynthia and Abe Steinberger.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #474, 2008, chromogenic print, 90.8 x 60 inches. Collection of Cynthia and Abe Steinberger.

Taryn Simon’s compilation of found photographs from the New York Public Library are a fascinating document of both the city and the archive as she brings together photographs of women in veils in one work and abandoned buildings in another and swimming pools in a third. Simon shows the photos and the objects in each category—each compilation is drawn form a single subject file in the picture collection—as being both similar to one another and also unique. It is both Benjaminian and Goldsmithesque in its use of found material and its display of collecting practices as temporal experiences that parallel the spatial experience of the flaneur in the city.

Other works like Ry Rocklen’s “Blue Eyed Worshipper” which plays on antiquities at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cindy Sherman’s “Untitled #474” which sees the artist dress up as an elite art collector, and James Welling’s “Morgan Great Hall” which is a beautiful, neon inkjet print of the Wadsworth Atheneum, likewise play insightfully with the idea of the collection, the museum, and the city as modern sites of associative logic and happenstance as much as of careful planning. These works encourage visitors to extend the exhibit’s flanerie to other museums and other collections that equally define and are defined by modernity, the urban experience, and the social relations of them.

James Welling, Morgan Great Hall, 2014, inkjet print, 21 x 31.5 inches. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Purchased through a gift from Nancy D. Grover in honor of Robinson A. Grover (1936-2015)

James Welling, Morgan Great Hall, 2014, inkjet print, 21 x 31.5 inches. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Purchased through a gift from Nancy D. Grover in honor of Robinson A. Grover (1936-2015)

However, the exhibit tries too hard to cover too much of what Benjamin described in a book that is over a thousand pages long and wasn’t even finished. It would have done better to focus more closely on the flaneur and the experience of urban life because this is what is most compelling about the exhibit and, arguably, about The Arcades Project. (An exhibit with similar subject matter currently at the Barnes Museum in Philadelphia seems to be taking this approach.)

Shortcomings aside, this exhibit is an intriguing call for all of us to engage with time and space, with the past and the present, with the city and the nation and the world in a way that embraces those associative logics and the non-linear time of the archive and the collection, in a way that embraces coincidence and juxtaposition rather than clear cause and effect. The exhibit is a call to stroll through the museum and stroll through the city in a way that lets the unexpected guide us. It is here on side streets, in bodegas, or in arcades that we will find new ideas and new ways of being. It is here in museums, in archives, and in collections that we will find ways to both embrace and confront the landscapes of the past and the present.

Check out 5 covered arcades in Paris. See our previous coverage of the exhibits in the Jewish Museum.