Welcome back to our regular column on “Must Visit Places” in NYC’s neighborhoods, written by one of our contributors who are residents of that neighborhood. This week’s guide is by Untapped New York tour guide Alan Cohen.

“Upstate” Manhattan has a decided residential feel, and it also contains many gems for any lover of things New York. You have to come here to really know our beloved city. If you’d like to visit the oldest house in Manhattan, see the best views in any park in the City, enjoy great food and drinks, all for one subway fare, then you must visit the Heights, even more recently made famous by the release of the Lin Manuel-Miranda film In the Heights.

Washington Heights is generally held to run from 155th Street on the south to Dyckman Street on the north and from the East River to the Hudson. The neighborhood includes Hudson Heights (north of 181st Street and west of Broadway) and Fort George (north of 181st Street and east of Broadway). Historically, the high rocky ridge that dominates the western part of northern Manhattan played a role in the American Revolution (the site of Fort Washington) as well as becoming a desired location for Gilded Age estates with magnificent Hudson River views.

With the development first of rapid mass transit at the start of the 20th century (IRT line, now the 1) and then the addition of the IND (A and C lines) in the early 1930s the area expanded quickly. With an easy commute to jobs downtown and an abundant stock of low-rise, predominantly art deco apartment buildings, living in the Heights became a residential step up from tenement housing in lower Manhattan.

While numerous ethnic groups had lived side by side in the Heights, some populations, like the Greeks, have largely relocated, while others, like Jews and Irish, have remained. By the 1960s, Dominicans became the predominant ethnic group, bringing a different flavor to the shopping and restaurants as well as the sounds of Spanish language and music to the streets. While Dominicans are still the dominant group in the Heights, immigrants from other Latin American countries have added to the diversity.

Between the 1980s and early 1990s, parts of the Heights had become home to the crack epidemic and the violence that accompanied it. Working with local police, determined individuals and diverse community groups united to fight the scourge, and crime dropped. Today the area is one of the safest in Manhattan. With low crime, relatively affordable spacious apartments, an abundance of parks, and an easy commute to midtown, the Heights has seen real estate prices soaring and people coming just for the day or to explore some of the must-see sights. And, oh, it hasn’t hurt that Lin-Manuel Miranda has celebrated the neighborhood in his hit musical and film, In the Heights, to become a Hollywood film produced by Jay-Z.

Historical Sites

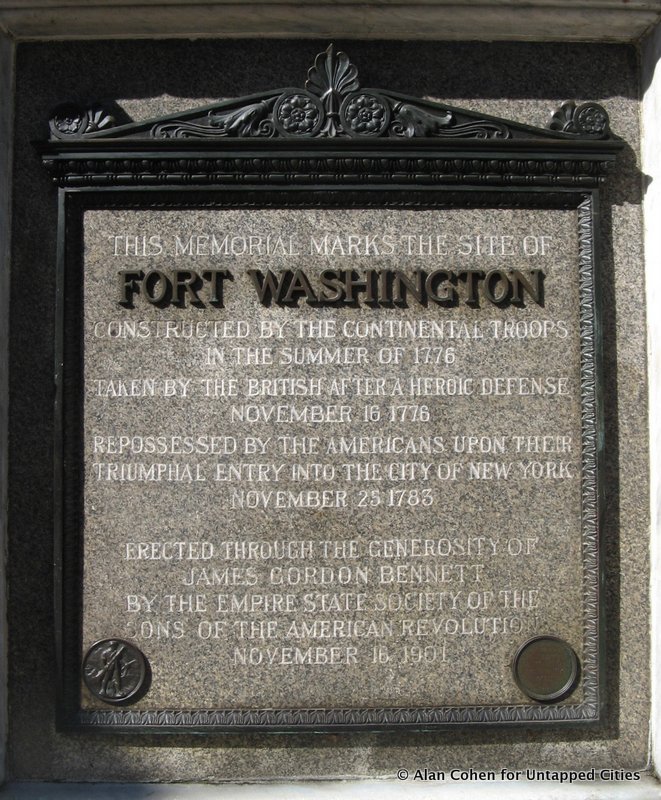

The highest natural point on Manhattan is found in Bennett Park located at about 183rd Street and Pinehurst Avenue. There’s an official plaque set into the rock, marking it as 265.05 feet above sea level. Bennett Park was the site of Fort Washington, the last stronghold in Manhattan of General Washington’s army and a resounding defeat by the Hessian and British onslaught. There is a replica of a Revolutionary War cannon, playground equipment, and a comfort station.

The Heights has two must-have historic sites if you want to see places largely intact.

Little Red Lighthouse

Children’s literature matters! The Little Red Lighthouse is the only lighthouse remaining on Manhattan island, albeit a non-functioning one, is the subject of the 1942 beloved children’s book The Little Red Lighthouse and the Great Gray Bridge, written by Hildegarde Swift and illustrated by Lynd Ward. The lighthouse, originally located at Sandy Hook, New Jersey, was placed on a spit of land named Jeffrey’s Hook, a navigation hazard throughout much of our early history.

A variety of warning devices were used over time in this spot, culminating in the 1921 installation of this 40-ft. tall cast iron light and fog bell. By 1931 the lights of the newly erected George Washington Bridge directly overhead illuminated the river beneath and rendered the lighthouse obsolete. Decommissioned in 1947, the lighthouse was scheduled to be sold for scrap in 1951. The well-known story of the friendship between the little round lighthouse and the mighty gray bridge galvanized children and their parents to advocate, successfully, for the preservation of the structure. Now, an annual festival is held in September to include a book reading and tour. The lighthouse has also been opened for visits during Open House New York in the fall and through NYC Park Ranger events. Even if you don’t get to go in, walking or biking past it is a visual treat.

To visit: Take the A train or a bus (M98 or M4) to 181st Street. Walk west to Plaza Lafayette. Cross the footbridge and take a left down the path under the overpass. Cross over the railroad tracks and follow the path to the left (south). The lighthouse is almost directly under the George Washington Bridge.

The High Bridge and High Bridge Water Tower

New Yorkers love to boast that our free tap water is great stuff, better than bottled water. While the first settlers in New Amsterdam may have enjoyed healthy, delicious local water from ponds, wells, and springs, the city’s population outgrew and polluted its local water supply. By 1835 we were short on water to fight fires, and local water was generally foul. If you could afford it, you bought bottled water or had it carted in from “sweet” wells.

City planners understood the dire situation and commissioned a major feat of engineering: the construction of a 41-mile long, gravity-fed system bringing ample, healthful water into Manhattan. This monumental task entailed damming the Croton River in Westchester County and constructing a series of conduits, ventilation towers, a receiving reservoir (where the Great Lawn is now in Central Park), and a distributing reservoir (now the site of the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street).

To cross the Harlem River, the High Bridge was constructed to carry the metal water pipe into Manhattan. The Croton Aqueduct system was constructed between 1837 and 1842 when it opened with a major celebration. The stone, Roman-like aqueduct went into use in 1848, replacing a temporary system across the river. The walkway over the High Bridge was added later and opened only to foot traffic in 1864. The Water Tower, a Romanesque Revival structure that looks like it needs a castle to guard, was added in 1872 to pump water up to the top of the hill were a reservoir was constructed (replaced by the High Bridge Park public swimming pool).

The original Croton Aqueduct became obsolete as our need for water in the ever-expanding city demanded more than this system could provide. The bridge was deteriorating during the 1960s, then entirely closed from the cash-strapped 1970s on and essentially allowed to decay. Community action with eventual support from various mayors and over $100 million from public and private sources enabled the rehabilitation of the High Bridge, which opened for bicycles and pedestrians again in 2015.

To Visit:

From the Manhattan side, enter Highbridge Park at West 172nd Street and Amsterdam Avenue, then walk east to the High Bridge Water Tower Terrace staircase and down to the bridge level. From the Bronx side, enter at University Avenue and 170th Street in Highbridge.

For ADA access, use the ramp at 167th Street and Edgecombe Avenue on the Manhattan side or the ramp north of 170th Street and University Avenue on the Bronx side.