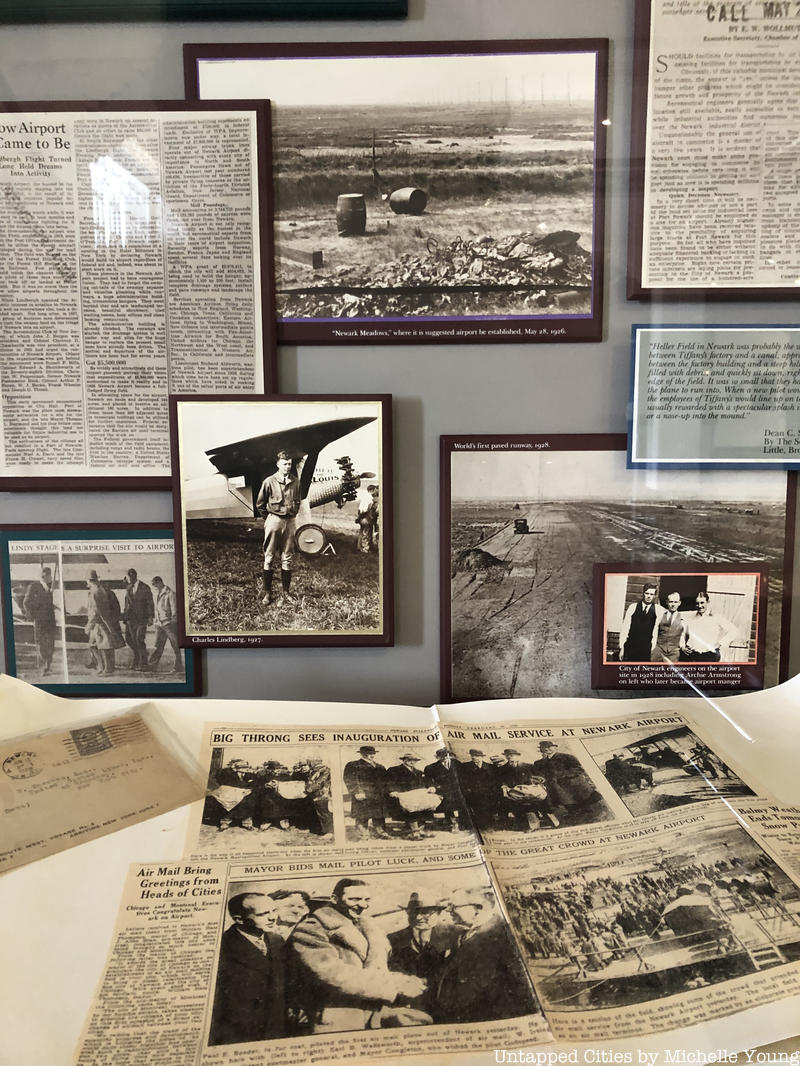

Is it possible to have an architecturally significant airport terminal, literally hidden in plain sight? It is, if it’s been picked up and moved a half mile, its original entrance tucked into an internal courtyard, and is forgotten by the public. Such is the understatedly epic story of Building 1, an Art Deco beauty built in 1935 as the original terminal building of what was then Newark Metropolitan Airport. Among its numerous claims to fame: Amelia Earhart, Wiley Post, and Charles Lindbergh all flew in and out of here, including on some record breaking flights. In fact, Newark Airport had the most active landing strip in the United States in the 1920s and ’30s, serving as the East Coast terminus of the Air Mail. Atop Building 1 is one of the first air traffic control centers in the country, and the whole building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Richard Southwick, Partner and Director of Historic Preservation at Beyer Blinder Belle, who led the adaptive reuse of Building 1 called it his “favorite project overall,” in a recent interview with us, while discussing his many high-profile restorations over the years including the TWA Hotel, Grand Central Terminal, The Frick Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the New York Botanical Garden, and many more. He calls Building 1, “the first modern terminal anywhere in the nation.” Upon Southwick’s recommendation, we took a visit last week with the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey.

The outdoor balcony outside the original control tower

The outdoor balcony outside the original control tower

Occupied by the U.S. Army During World War II, by the end the war, the concrete terminal was considered too small for operations. After years of being used by the United State Postal Service for airmail operation, the terminal fell into disuse. More than half a century later, threatened by the extension of a runway, the entire building was cut into thirds and moved half a mile down the airport taxiway in 1999. It was one of the largest ever building moves undertaken historically in the United States and the adaptive reuse effort saved the building from demolition. The building was seamed back together — you can still see where this was done on the exterior and interior — and expanded with a 70,000 square foot new addition that tripled the size of the building.

Today, it is home to the Port Authority Police Department, airport administration offices, an operations center, and rescue and firefighting departments. The sense of history is palpable throughout the building, going beyond the architecture itself, from historic exhibitions on the ground floor to a restored captain’s quarters on the second floor. Two of ten original WPA murals by Arshile Gorky from the series “Aviation: Evolution of Forms under Aerodynamic Limitations,” were uncovered in the restoration process, and reproductions are on display on the second floor (the originals are in the Newark Museum). Originally planned for Brooklyn’s Floyd Bennett Field, another historic flight facility in the New York City area, Gorky was reassigned by the Works Progress Administration to Newark Airport where he completed the paintings in 1937.

The former main entrance of the terminal looks plucked straight out of Miami Beach, featuring a semi-circular entrance canopy with Art Deco lettering. Aluminum grillwork showing seagulls in flight sits above the three-section entranceway. The revolving door is enclosed on the sides to further emphasize the verticality of the Art Deco design of the building. The entrance overhang extends beyond other smaller semi-circular elements — the revolving door, the air traffic control tower, the bowed windows on the second floor — throughout the central part of the facade. The first floor begins six steps above ground level, with semi-circular steps leading up to the entrance. Two wings come off of this central block, “bent back from the air-field elevation as if in flight,” according to the description in the nomination form for the building in the National Register for Historic Places.

As described in the National Register, the original building had marquees “which projected out from the building and under which airplanes were brought and loaded.” Today, a pattern of radiating stone paths with in-floor lights were designed that reference the former runway and serves as a nod to more records for the terminal: Newark Airport was where the first night landings in the country took place and where the first paved runway was located, made of cinder pavement. Southwick has repeated this design idea at the TWA Hotel, where Connie the vintage TWA Constellation plane sits on a fake runway with lights and markings.

A 9/11 Memorial sculpture by Pentagram is the centerpiece of the courtyard which brings together original terminal and new extension

A 9/11 Memorial sculpture by Pentagram is the centerpiece of the courtyard which brings together original terminal and new extension

The 80-foot long main concourse, now the entrance lobby to the building, originally provided access to interior corridors which led to waiting rooms. The walls and columns are faced with polished marble, and bird wings made of plaster come off the top of the columns. According to the National Register for Historic Places, “The design incorporated large areas of glass and contained an interior of fanciful, yet restrained decoration which relied heavily on geometric motifs which were interspersed with references to the theme of flight.” When the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places, much of the original lobby walls was covered in sheetrock and the original lighting fixtures and grillwork were missing, but the terrazzo floor and ceilings were still in place.

Passengers would get to their planes by exiting from doors either from the concourse or the waiting room. The main floor also had ticketing counters, rooms to sort the Air Mail, the office of the State Aviation Commission, and place for the airport doctor and the “newspaper man who wrote daily columns about life at the port,” as stated in the National Register for Historic Places.

The second floor originally had one wing of bedrooms and one wing of offices, an air traffic control center, in addition to a lounge and lobby, which today contains the recreations of Gorky’s work. One of the captain’s rooms, restored, remains on the second floor between offices. On the floor of this room, you can see where the the seams in the building where it was connected back together.

Inside the bathroom of the captain’s room

Inside the bathroom of the captain’s room

Today, the central space on the second floor contains a control room from which the original spiral staircase still leads up to the glass-enclosed control tower. It is here that the Federal Bureau of Air Commerce established the first series of rules that controlled air traffic. The Bureau would become the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA), which would become the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

Control center, from which the tower is accessed through the spiral staircase

Control center, from which the tower is accessed through the spiral staircase

A historic exhibit is also inside the control tower

A historic exhibit is also inside the control tower

The lobby of Building 1 is open to the public, though this is a generally little known fact. Southwick concludes about this very unique adaptive reuse project: “There was a little bit of everything: new construction, old construction, interpretation, historic exhibits, moving the building which is one of the tools in our preservation toolbox. [It was] the biggest move of its type in the history of the country. And it’s open to the public!” Here is a look at the historic exhibitions you can see:

Take a visit to Building 1, located at 1 Conrad Road inside Newark International Airport and get a glimpse of the airport’s glorious Art Deco past.

Next, check out the Seaman’s Church, hidden inside Port Newark.