The Frick Collection‘s move from its opulent house on 70th Street to the Met Breuer Building, up five blocks on Madison Avenue may go down as one of the oddest pairings in art history. It nonetheless makes sense. After all, while the Frick mansion is being renovated and expanded you couldn’t put the Frick Collection just anywhere. The Frick has temporarily relocated itself from one masterpiece, the Gilded Age house of its founder, to another. Its new Brutalist home, lovingly described as “a sculpture in its own right” by then-Met Director Thomas Campbell, demands respect.

But what everybody wonders is: Will it work? Can the Frick successfully resettle its old masters and decorative arts from their palatial home to the geometric, monochromatic Breuer?

As may always be true of major transitions, the answer is that there will be winners and losers. Some will flourish and some will suffer. The clearest beneficiaries of the move are the decorative arts. We can now see the Limoges enamels, Meissen porcelain, and Italian bronzes up close and well-lit in their individual splendor. And the huge rock-star paintings, like Veronese’s panels or Fragonard’s Pursuit of Love, dominate their new walls. Each is an individual tour de force, no longer competing with other works of art.

Beneath Breuer’s Lights a Loop of Frick Treasures

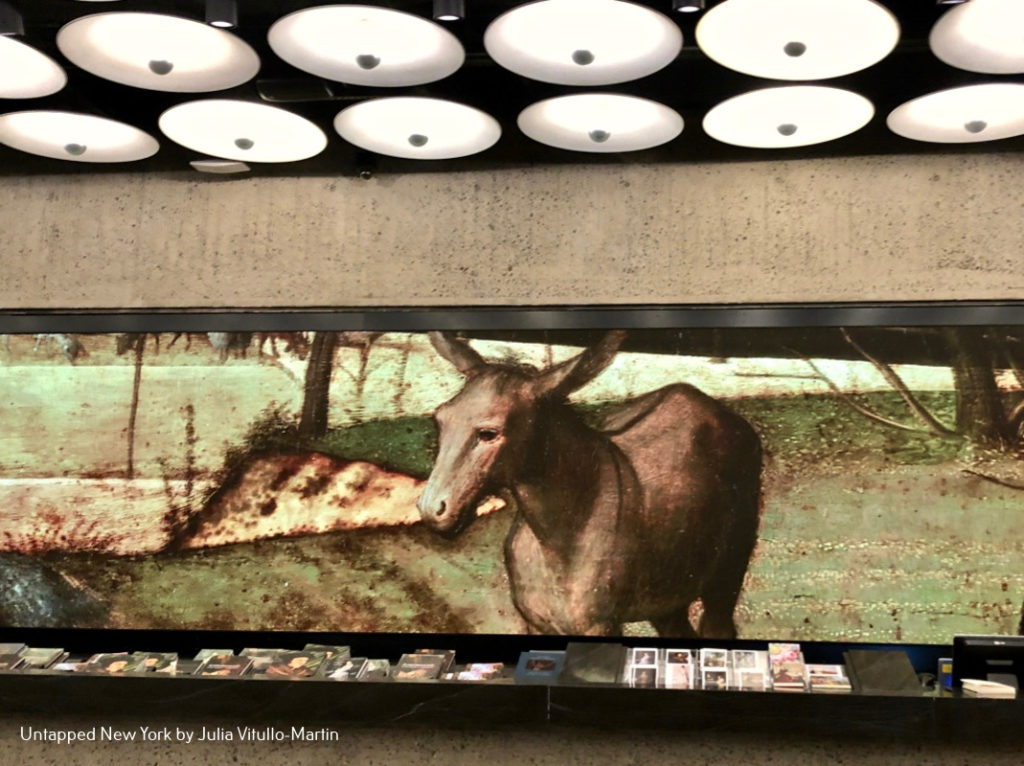

As you enter the Frick Madison you see above you the Breuer lobby’s extraordinary ceiling of lights (375 LED bulbs!). Immediately before you a long digital loop introduces the treasures to come, often in their original settings in the Frick mansion. Many of the images are abstract—a white-stockinged leg ending in a gorgeous red shoe, colorful foliage from Fragonard, flowers from Mughal carpets. My favorite is Bellini’s donkey, who stands looking a bit forlorn in the Tuscan landscape.

The loop is both an introduction—morsels of what you’re about to see—and a useful reminder at the end of your tour of what you might have missed. As I started to leave after a few hours upstairs, this beautiful gilded face appeared, encouraging me to return to the fourth floor to find him.

And there he was in a room of glorious French decorative arts, staring out from the center of an entablature fronting a blue Turquin marble table that had for decades stood at the Frick mansion below Ingres’ portrait of the Comtesse d’Haussonville. He is the work of Pierre Gouthière, master ciseleur-doreur (chaser-gilder) to King Louis XV and later to Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. Like most Frick visitors I’ve seen the table many times, but never concentrated on the gilded face until the curators brilliantly abstracted it for display in the loop. As chief curator Xavier Salomon hoped, the presentation helps visitors “realize that they’ve never looked at things properly,.”

The loop’s scenes from the mansion help you remember your favorites. The Frick’s West Gallery, for example, had Paolo Veronese’s two allegories, “The Choice Between Virtue and Vice,” to the left of the door, and “Wisdom and Strength,” to the right. The panels have now left their home for the first time since Henry Clay Frick had them installed..

Veronese Triumphant at the Frick Madison

At the Frick Madison, the two Veronese panels stand alone on their dark wall, unfettered by other paintings or beautiful carpets or even compatible Italian bronzes, now in an adjacent room. Veronese sought to educate his viewers of the dangers of a misled life. And so he does, with no distractions to hinder his message.

The Frick’s helpful free guide explains that Veronese transformed the popular theme of Hercules at the Crossroads. Instead of Hercules in a classical landscape he painted an encounter among fashionably dressed 16th-century Italians, the swells of their time. You see on the left the moment when the young man turns away from Vice, whose claw-like fingernails tear at his leg. He flees into the arms of laurel-crowned virtue. Up close it’s truly a little scary. Vice is a sphinx, lurking in the lower lefthand corner to warn viewers that if they fail to answer the sphinx’s question they will die. On the right, the sun shines above Divine Wisdom as she prevails over the brute force of Hercules, his left leg caught by a putto or Cupid.

Oh Those Italian Bronzes!

It makes sense that Henry Clay Frick, who made his fortune in steel, would acquire splendid works of art forged in metal. Many of the bronzes, like Veronese’s panels, date to the 16th century. Several involve Hercules, an ancient as well as Renaissance figure of immense strength. Pietro Tacca’s extraordinary bronze statue of the centaur Nessus trying to abduct Deianira, the wife of Hercules, dominates the room.

In the distance is Antico’s far smaller Hercules as an old man. In a February 2021 “Cocktails with a Curator,” Assistant Curator of Sculpture Giulio Dalvit says that Renaissance Italians were obsessed with antiquity. Ancient statues had just been unearthed and were the coolest things in the 15th century, says Dalvit, whose demeanor suggests he knows cool when he sees it. What’s more, copying was a creative process at the time because statues were often found in a fragmentary state, missing limbs or attributes that had to be carefully reconstructed by the artist.

Antico would have found many ancient sources of inspiration for the beard, the body, and the lion pelt of Hercules. But Antico’s work was virtually jewel-like, says Dalvit. Hercules’s locks and beard are gilded, and his eyes are silvered. The statue is dark, almost black, showing that Antico managed to find a chemical formula that would stabilize the appearance of dark bronze. It has amazingly survived 500 years.

Frick bought the statue for the incredibly low sum of $165 from JP Morgan’s collection. At the time other important bronze statues went for $100,000, says Dalvit, speculating that perhaps Frick alone realized its value. He kept it for his private collection, where it stayed until it was donated to the museum by his daughter in 1970.

Why Did Henry Clay Frick Choose Goya’s Forge?

Amidst magnificent paintings of aristocrats dressed in sumptuous gowns—and hung across from El Greco’s elegant St Jerome in his extraordinary rose cape—we see Francisco de Goya’s, The Forge. This painting is often dismissed by critics. Indeed, New Yorker writer Peter Schjeldahl recently said he would “pass” on The Forge: “The picture seems to me more akin to the artist’s anecdotal etchings—unnecessarily large for its content of a discrete muscular action—than to Goya’s more complexly inspired oils.”

This is clearly not how Henry Clay Frick, who acquired The Forge in 1914, saw it. He had built his fortune on the work of men like these. And although it is seldom emphasized, the steelworkers defeated him and his armed forces in the Homestead Strike of 1892. Frick’s 300 Pinkertons were “outnumbered, outgunned, and trapped” in a rout, concludes the Homestead Foundation. The Pinkertons were captured and forced to run a gauntlet of furious workers and sympathizers before being packed by the victorious steelworkers into trains and sent out of town to safety. Only after the governor of Pennsylvania summoned the National Guard, not really fair play, was Frick able to hire replacement workers.

As painter and photographer Tom Bianchi says in the new Frick book, The Sleeve Should be Illegal, Goya paints his steel worker as a “heroic figure.” Further, writes Bianchi, “My own instincts draw me to the raw beauty and power of the man with the hammer in mid-strike.” Yes. Raw beauty and power.

Xavier Salomon cites Helen Clay Frick’s statement that her father collected pictures that he found “pleasant to live with,” a description that doesn’t remotely fit The Forge. On the contrary, “with its dark, vigorous brushstrokes, harsh realism, and working-class subject it disrupts the serenity of its surroundings,” says Salomon. For Henry Clay Frick, The Forge must have had “strong, if complex, resonance.”

And it stands alone, unparalleled in the collection.

Face to Face Again at Frick Madison

Frick director Ian Wardropper says that Henry Clay Frick hung his Living Hall with portraits of “principled men,” such as St. Jerome and Sir Thomas More, as well as Giovanni Bellini’s “St. Francis in Ecstasy,” facing St. Jerome opposite. The Frick Collection retained this format for decades in part out of deference to Frick himself but also, Wardropper told Hyperallergic, “because it’s really hard to beat the hang that he did.” Wardropper admires “the way the Middle Eastern carpet is harmonious with Chinese vases — it’s such a perfect impression of his taste that we leave it that way.”

All have now been dispersed in the Frick Madison, but to interesting effect. Sir Thomas More and his arch enemy, Thomas Cromwell, again face one another, but without the intervening fire place to soften the cold stares. Cromwell looks heavy, almost thuggish, while More looks confidently peaceful, as if he were Sir Laurence Olivier’s uncle. Frick’s friend, the painter Charles Ricketts, summarized the scene in 1919: “Imagine Sir Thomas More, the beautiful saint, and [Thomas] Cromwell, the monster, united in history, art, and tragedy, now facing each other, united by Holbein and time and chance.”

In a Cocktails with a Curator segment on Holbein, Xavier Salomon calls the More painting one of the most beloved at the Frick. He calls it “absolutely staggering.” (There doesn’t seem to be a comparable segment on Cromwell). Salomon says, “You realize what made Holbein celebrated was the attention to detail,” naming the chain, the textiles—especially the velvet and the fur of the red sleeve—the elegant hands. All “truly miraculous,” says Salomon.

At the Frick mansion, Giovanni Bellini’s St Francis in the Desert stood opposite the two great Holbein portraits. At the Frick Madison Bellini’s St Francis stands alone in its own room, lit by one of Breuer’s trapezoidal windows. St Francis may have more superlatives than any other Frick painting. The Washington Post’s Sebastian Smee, for example, called it the most beautiful painting in America. Xavier Salomon calls it “arguably the most famous painting in the collection” as well as an extraordinary and mysterious work of art.

Ironically, Henry Clay Frick initially disliked Bellini’s St Francis, and arranged to return it to M. Knoedler’s Gallery. A horrified Sir Joseph Duveen, a rival dealer who was with Frick on 70th Street at the time, persuaded him that St Francis was the pinnacle of the Italian Renaissance. Frick kept it, and grew to cherish it. Because of the frequency with which the Frick had to replace the carpet, director Ian Wardropper concluded that St Francis was their most viewed painting.

The Former Met Breuer Shines as the Frick Madison

Can the fabulous Frick Collection leave its luxurious home and find love in the severely Brutalist Breuer building? The answer seems to be yes. The building’s open spaces not only enhance the art but also seem to lift the human spirit. Somehow in its earlier incarnation as the Met Breuer the building didn’t sing, or at least didn’t sing to New Yorkers, who stayed away in droves.

Critic Alexandra Lange, for one, had “been looking forward to seeing what old art would look like in midcentury space.” But she concluded that the works didn’t seem to be gaining anything from the Breuer: “The gilt didn’t glitter. The painted skies didn’t call to the winking windows. Klimt looked just okay. I found myself looking at the heavy, snake-edged shadow of the frame on the Corot, rather than the Corot painting itself.” At the Frick Madison people are looking devotedly and precisely at the art.

The gorgeous staircases are open, letting us see up close Breuer’s renowned materials.

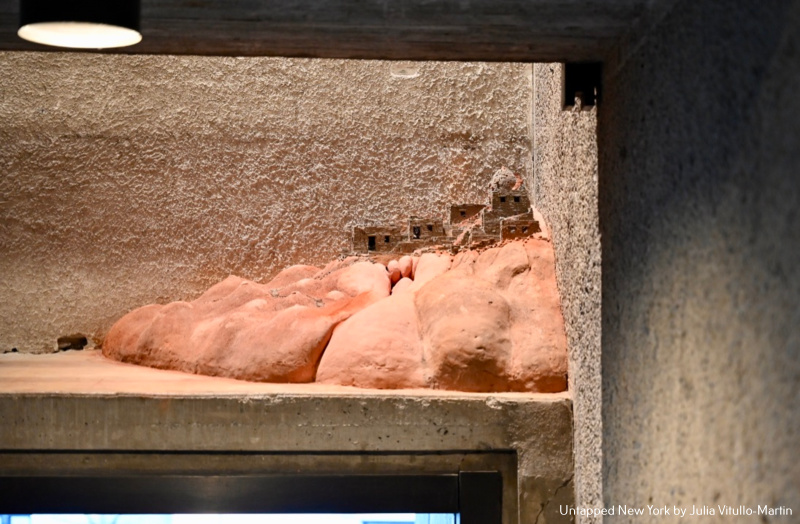

The Frick Madison has retained Charles Simonds’s Dwellings, one of the delightful treasures originally installed by the Whitney.

On leaving the Frick Madison New Yorkers can be grateful that Marcel Breuer’s building embracing minimalism, harmony, and elegance has a new life, at least for two years.

Next, check out 15 secrets of the Frick Collection. Julia Vitullo-Martin can be reached at @JuliaManhattan.