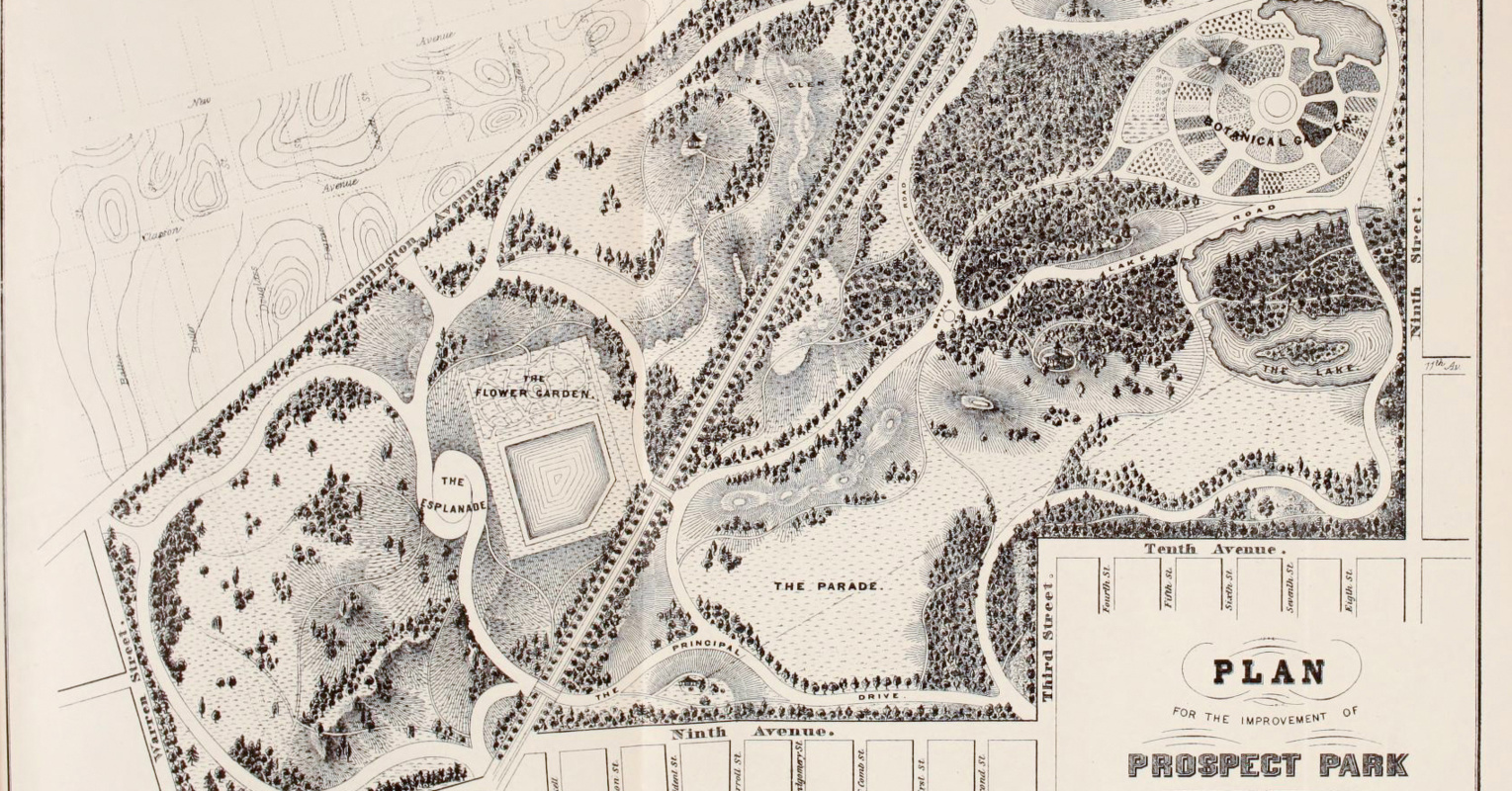

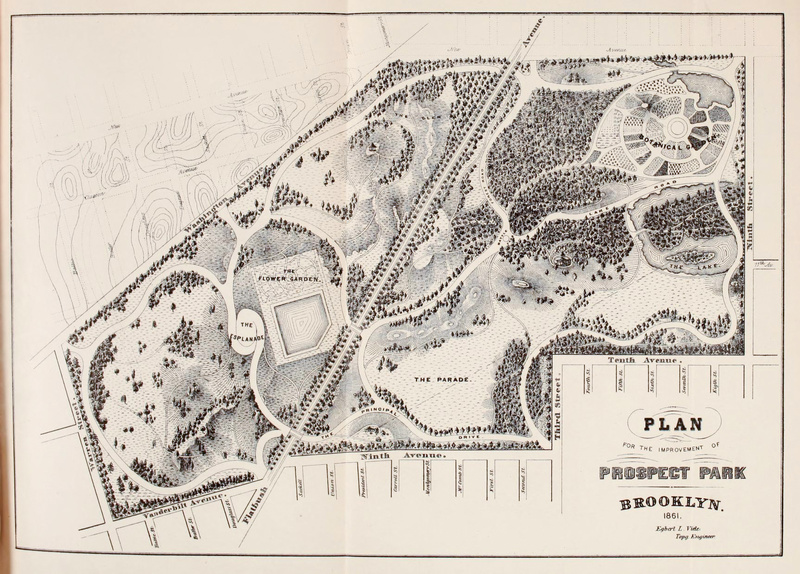

The original plan for Prospect Park was designed in 1861 — not by the renowned Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux — but by a man named Egbert L. Viele. Viele envisioned a drastically different park than what we know today, centering his design around Flatbush Avenue and extending the park northward. The park would have also been 55% smaller than it is today.

Viele was a civil engineer who had been the chief engineer of Central Park. He had a variety of occupations in his life: a topographer for New York City, an army officer, the city park commissioner, a brigadier general during the Civil War, and a member of Congress. A graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, he was known to be stern and authoritarian. Viele wanted to be referred to as Colonel during the project. He approached the plan more like an engineer rather than a designer, and the beautiful features such as the waterfalls, the Lullwater, Music Island, and the Oriental Pavilion that we know today were absent from his compact design.

In his 320-acre plan, Viele wanted Mount Prospect to give visitors a view of Manhattan, New Jersey, Staten Island, and Brooklyn from the park. Brooklyn’s reservoir was also located at Mount Prospect at the time, and the land in the park would protect the reservoir from potential contamination by residential buildings. The park would be divided almost midway by Flatbush Avenue, covering what was known as the East Side Lands by extending from Ninth Street and Prospect Park West in Park Slope east beyond Flatbush Avenue. This is where the Brooklyn Museum, the Brooklyn Public Library, and the Botanic Gardens exist today, and it would have placed the park further north than it currently is.

The plan included carriage roads that wound up Mount Prospect, giving passengers at the top a breathtaking view from 200 feet above sea level. A botanical garden in the southeast corner, on 9th Street, was to be divided by circular, interconnecting pathways. West of the garden was a small lake in the approximate area where Swan Boat Lake would later appear. A meadow, which Viele called “The Parade,” was placed between 3rd Street and Flatbush Avenue. This spot would become the northern end of Long Meadow. Viele stated that he wanted the park to be “a rural resort, where people of all classes, escaping the glare, and glitter, and turmoil of the city, might find relief for the mind, and physical recreation.”

Viele considered the land to be naturally aesthetic, and stated that “artificial constructions would defeat the primary object of the park as a rural resort.” He noted that the natural hills and meadows “require but little aid,” which was a reference to Olmsted and Vaux’s Central Park, in which a lake, hills, and lawns were constructed to improve the natural landscape. Viele also criticized Central Park’s artificial buildings and structures. But despite Viele’s admiration of the area, the land was undesirable and disease-ridden, according to a letter to the Eagle from a Brooklyn resident. It was described as “a plague-spot” of sewage and dysentery. The northern part of the land would be difficult to work with, as it was part swampy, unreliable land, and part hard clay and stone.

With the onset of the Civil War, Viele’s plans were put on pause for five years, giving the Parks Commissioner time to reconsider his design. Architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux undertook a revision of the design in 1865. Establishing the boundaries of today’s 585-acre Prospect Park, Olmsted and Vaux envisioned a very different landscape: they urged for an expansion toward the town of Flatbush, a lake in the park, and a solution to Flatbush Avenue’s intersection of the park, something Viele admitted “might be regarded as a serious blemish to the beauty of the finished park.”

Olmsted and Vaux solved that by expanding the overall size of Prospect Park and extending it further south, thereby allowing for two well-apportioned sections of the park divided by function: institutions like the Brooklyn Museum, the Brooklyn Botanical Garden, and the Brooklyn Library, could be contained within the triangular wedge between Flatbush Avenue and Washington Avenue, while the naturalistic portion of the park with its open meadows, meandering paths, and forested woodlands, could be located fully west of Flatbush Avenue with enough space to express the architects’ ideas, building upon their success with Central Park.

Viele’s original plan put the main entrance in almost the same location as where Olmsted and Vaux landed on (although the entrance faced west instead of north), but Viele’s park would have been 55% smaller, extending about five more blocks northeast from the entrance into the heart of Prospect Heights’ brownstone-lined streets today. The angle of Flatbush Avenue against the street grid, much like Broadway in Manhattan, posed a difficult challenge to Viele’s design. The overpasses that would have crossed the avenue would have been an expense that could have been put toward gaining additional land. By expanding the grounds, Vaux’s plan made room for a much larger lake that could be used in the winter for ice skating.

After the revisions of Olmsted and Vaux, the park was about equally divided into three distinct parts: a wooded ravine in the east, a meadow in the north and west, and a large lake in the south. They also added an oval plaza at the northern end of the park, now called Grand Army Plaza, to compensate for the very narrow entrance of the park that was less grandiose than what one would like for such a vast civic undertaking. The final boundaries of the park are not restricted by reservoirs or divided by roads, and a ridge of green earth just within the borders creates an illusion of a sweeping meadow by blocking out the surrounding buildings.

By 1873, Prospect Park’s construction was finished, and in the early 19th century it was widely used for sports such as archery, croquet, and ice skating. It has since been a popular natural haven for New Yorkers amid the busy streets of Brooklyn.

Next, check out “The Top Ten Secrets of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park” and Prospect Park’s Endale Arch Magnificently Restored