Today, the Polonsky Exhibition of The New York Public Library’s Treasurers will open at Gottesman Hall, a 6,400-square-foot marble exhibition space inside the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, the landmarked 42nd Street library. On display will be more than 250 items spanning over 4,000 years of history from the Library’s renowned research collection, many priceless artifacts of national and international significance. As Declan Kiely, Director of Special Collections and Exhibitions for the New York Public Library, comments: “The two chief functions of this exhibition are to provide visitors with an emotional experience and a mine of practical truth… My hope is that visitors will gain renewed understanding and appreciation for the variety and diversity of the Library’s special collections, and how the objects featured in the exhibition have been preserved for future generations.”

The Polonsky Exhibition exhibition is broken up into nine distinct sections: Beginnings, Performance, Explorations, Fortitude, The Written Word, The Visual World, Childhood, Belief, and New York City. Each section aims to tell a unique story, connecting each item on display to a broader historical narrative, one which is expanding continually. In addition to written label texts for each item, a select few will also be accompanies by an audio guide featuring commentaries from American actress, playwright, and professor Anna Deavere Smith.

Here are 11 fascinating items on display at The Polonsky Exhibition!

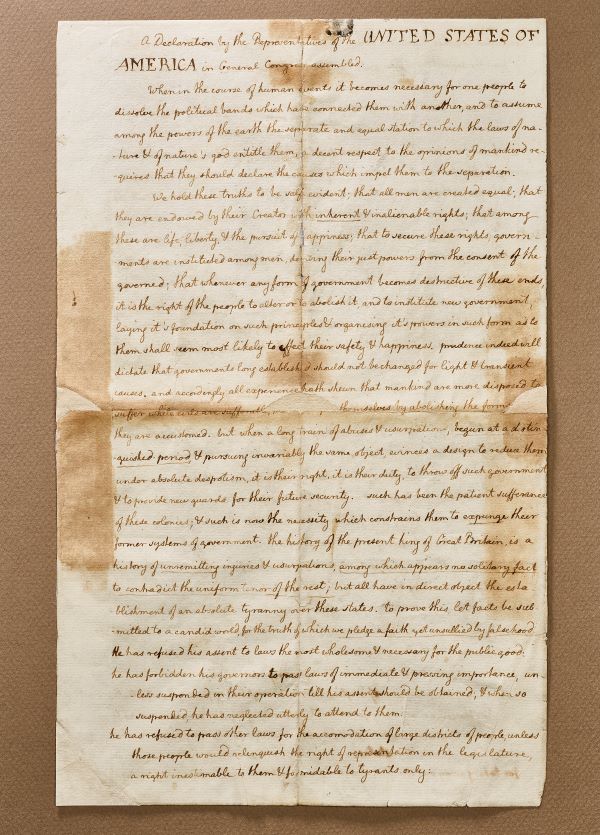

1. Thomas Jefferson’s handwritten copy of the Declaration of Independence

As one of only six manuscript versions known to have survived in the hands of Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration of Independence on display at the Polonsky Exhibition is a sight to behold. In particular, this version of the Declaration of Independence was made by Jefferson for a friend shortly after the document’s ratification on July 4, 1776, as a means of preserving his original draft of the document, which had been significantly altered by the Second Continental Congress. A striking difference between the original and final versions is the substitution of “inherent and inalienable rights” for “inherent and unalienable rights.”

Most important in terms of significant changes are a series of underlinings highlighting passages that were removed from the final version. One of these included a passionate rebuke of African chattel slavery and the slave trade, with Jefferson referring to it as being a “cruel war against human nature itself” and “an assemblage of horrors.” However, though almost exclusive blame was placed on King George III and the British for bringing slavery to the colonies, Jefferson himself was a known enslaver—having owned more than 600 slaves throughout his life. In the end, while even this version of the Declaration of Independence might not have actually fully supported the notion “that all men are created equal,” it gives us a glimpse into what could have been. It allows us to speculate on what the future of the new republic might have looked like if questions on the validity of slavery had been brought to the forefront of one of the republic’s most important founding documents.