One of Staten Island’s biggest secrets is that an estimated 300,000 tons of good quality iron ore were mined around Todt Hill, Emerson Hill, and Grymes Hill in the 1830s through 1880s! It was refined and used in iron foundries and also finely ground for use as the pigment red ochre. However, if you search for evidence, you will only find deserted pits, brown-colored soil, a street name, and a Dutch Colonial farmhouse where an iron mine owner once lived — as well as a road named Iron Mine Drive around where the mines were located. No machinery or other artifacts remain. Some mines are flooded and one area is called “iron ponds.”

By the 1880s, iron deposits around Lake Superior (the largest ever discovered in the United States) dominated American iron mining. They produced iron ore more economically than the Staten Island mines, which were becoming mined out and running out of funds. However, there was still some mining in 1890, as seen in this photo from the Staten Island Historical Society:

The first Europeans to settle in the area were attracted by the rich deposits of iron ore, exposed by a receding glacier, which made mining easy. According to a New York Times article, the first record documenting mining was a mid-17th century patent for land given to John Palmer by Thomas Dongan, the British Governor of the Province of New York.

This patent mentioned present-day Todt Hill (at 410 feet, the highest point on the Atlantic coast from Maine to Florida) as “Iron Hill.” The ore found on the island was hematite, a common name for limonite. It was also known as “shot ore” because it consisted of various-sized round nodules. The ore was located near the surface and was probably mined by hand. The 1915 New York Times article states that “Specimens of the ‘shot ore’ can be had for the picking up.” Today’s Dongan Hills neighborhood (east of Todt Hill and running east from Richmond Road to Ocean Breeze Park and north from Seaview Avenue to Old Town Road and Quintard Street) was named for Governor Dongan. Quintard Street is one of only several streets in New York City that starts with Q.

A New York City Department of Parks & Recreation Historical Signs Project sign at Sports Park (just south of the Staten Island Expressway and just west of Todt Hill Road) explains that “From the 1600s to the end of the Revolutionary War, the Dutch name Yserberg or its English translation, Iron Mount, referred to the area’s exceptional iron resources. Evidence of iron mining on Todt Hill dates to 1644, but it is known that intensive mining took place between 1832 and 1881.

In 1832, Walter Dongan granted Warmaldus Cooper permission to mine the land at the intersection of Ocean Terrace and Todt Hill. Business boomed in 1865 when iron ore was discovered in the serpentine rock that stretches from the Kill Van Kull to Fresh Kills. Because the iron lay close to the surface, it could be extracted with relative ease.” Walter Dongan was a nephew of Governor Thomas Dongan, who issued the 17th-century patent for Staten Island land first used for mining. There were more than 12 open pit mine sites, and eight mining “certificates of organization” were filed at the County Clerk’s Office between 1859 and 1881.

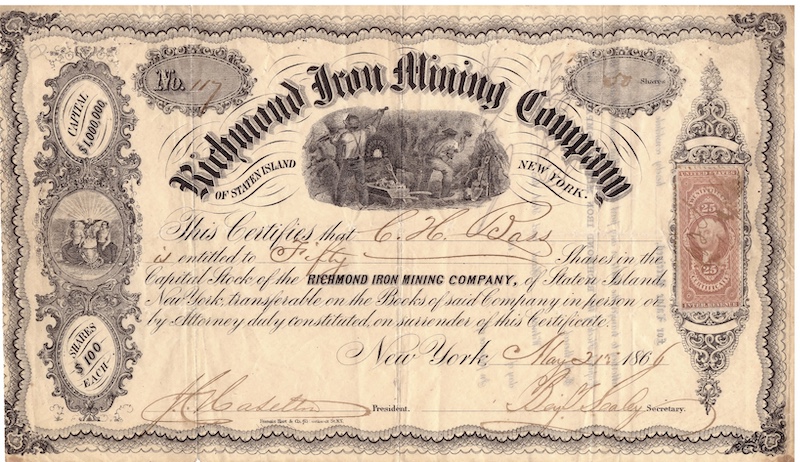

The first map below, attributed to Raymond Safford in “Iron Mining on Staten Island,” shows the company’s Tyson Four Corners Mine. It was on 56 acres north of the then dirt Victory Boulevard, between Jewett Avenue and Manor Road in Castleton (or Meier’s Corners) near the Westerleigh neighborhood. This article explains that in 1869, the Richmond Iron Mining Company employed about 45 workers. They built their Richmond Mining Company Dock on Richmond Terrace just west of Van Street (a little less than a mile from today’s Snug Harbor Cultural Center & Botanical Garden) in the West New Brighton Neighborhood. This company surveyed a route (shown on the map) between its mine and dock for the proposed Central Railroad of Staten Island that would also carry passengers This railroad would replace ore transport to the Port Richmond dock on wagons that turned Jewett Avenue red with spilled ore and could get bogged down in mud during rainy weather. The railroad bed was constructed, and plans for a future extension to the south shore via the county seat at today’s Historic Richmond Town were floated, but the rails were never laid for any portion of the line.

“Iron Mining on Staten Island” also includes the following map showing the “Principal Iron Mining Areas” around Todt Hill.

According to the book Westerleigh: The Town that Temperance Built, the miners were mostly German and Irish immigrants who earned $1 to $1.25 per day and lived nearby. “The present location of the Manor Road Post Office was once an open-pit mine, with several smaller pits located along Richmond Turnpike (Victory Boulevard). Twelve tons an hour were excavated from ‘Iron Ore Hill.” By 1880, the Richmond Iron Mining Company’s open-pit mines were converted to an underground mine. Its main horizontal shaft was 100 feet long and accessed 10-12 foot thick ore veins. The Staten Island Leader on December 19, 1868, published an article stating that “The ore produced from the various mines upon the Island has been pronounced by competent authorities to be of a superior quality.”

In 1870 the Richmond County Gazette reported that “The Richmond Iron Mining Company a few days since ceased mining, or sending away from their work any ore already mined. The numerous wagons which carried the material from the mine to the landing at West Brighton were the cause of a good deal of dust and profanity while engaged in their work. It is to be hoped that the residents on the line of the road will now return to their former morality.”

However, the same newspaper reported in 1879 in an article “An Island Industry” that “Supervisor O’Brien, of Southfield, carries on an extensive business in mining and shipping iron ore. The mining is done by him at the Richmond mines, and thence the ore is carted to Townsend’s dock where a huge pile of it is at present waiting to be shipped. On Monday last six canal boats were lying at the wharf and a number of Staten Island laborers were busily engaged in loading them, the destination of the ore in this case being smelting works in Pennsylvania. In this business Mr. O’Brien keeps some thirty teams and about one hundred men in almost constant employment.” It is not clear if the Richmond Iron Mining Company reopened between 1870 and 1879 or if Timothy D. O’Brien operated a different mining operation.

The current Diggings website, which has a resource for locating where mining claims are and have been and where sites are being mined or were mined in the past, shows four former mines on the map below. It also documents that the Tyson Iron Mine and the Cooper and Hewitt Mine both closed around 1880.

The Staten Island Museum has a curious specimen of Iron-oxide replacement of plant roots that was collected in 1886-7 by Amos Smith at the iron mines in Westerleigh (Collections of Staten Island Museum #G4119).

Today, you will find an Iron Mine (or Ironmine) Drive, just east of Todt Hill Road. Staten Island borough historian Thomas Matteo told NY1, “You see the beautiful topography, the changing elevations—that was all mined out. That was a hill, and they just dug that out. So that beautiful topography is a result of iron mining.”

One of the last remnants of Staten Island’s iron mining past is the Lakeman-Cortelyou-Taylor House at 2286 Richmond Road, a stone Dutch Colonial style farmhouse, built around 1684. It was the home of David J. Tysen who opened iron mines on Todt Hill (not far from his home) and Jewett Avenue in the 1870s and shipped ore to steel mills in Pennsylvania. Though it was designated a New York landmark in December 2016, by March 2017 the home’s landmark status was overturned. The home is privately owned.

Get in touch with the author at [email protected].

Next, check out The Last Wooden Bridges on Staten Island!