Things to Do This Week in NYC: Dec. 11 -18

Discover all the ways you can rediscover NYC!

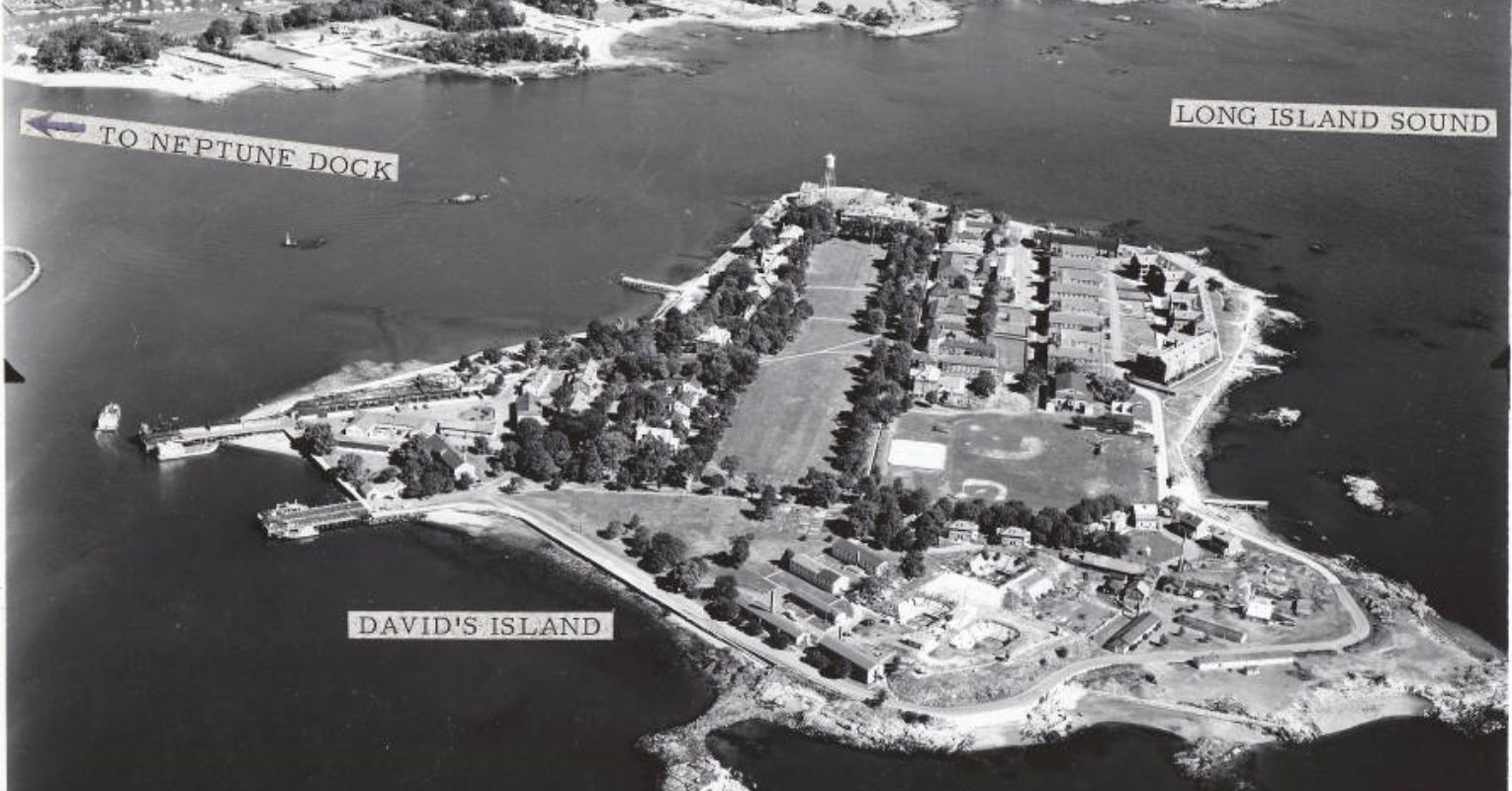

Just off the coast of New Rochelle, mixed in amongst a plethora of condo and mansion-dotted islands, lurks an ominously green, seemingly untouched patch of land, known as David’s Island. This speck of greenery, with its soaring bush and rocky edges, hides a century of military history, ambitious projects, and long-forgotten controversy between its rich pine and poplar trunks.

Few today would believe such an undeveloped island, only 1,700 feet from the mainland, exists in the sprawling metropolis of New York, and yet its 78-acres remain akin to the way they were when the Huguenots first arrived in 1689: bridgeless and buildingless. As one astute reporter put it, the island is the “capital for fizzled plans.”

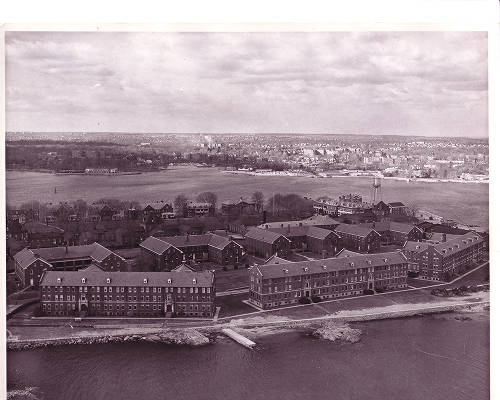

David’s Island, in Westchester County, started out as farmland, swapping owner to owner. Many bought the island with plans to build a factory, none of whom were able to bring such to fruition. Realizing its excellent location relative to New York City, the United States Army leased the island in 1862 and built De Camp Hospital. It became the Army’s largest general hospital during the Civil War, nursing soldiers from both North and South, and housing Confederate POWs after the Battle of Gettysburg. Following Union victory, the federal government purchased the entire island and turned it into the largest army recruiting and training center in the nation east of the Mississippi.

During reconstruction, the island served as the main battle station for the protection of New York City. Named Fort Slocum, the base occupied the whole of David’s Island and wielded three artillery batteries, each with long-range mortars and guns. Its position at the west end of the Long Island Sound was thought ideal for defense against Atlantic-born invasions. With no such invasion occurring, the base focussed its effort on recruit training in the lead-up to World War I, where it processed more than 100,000 soldiers a year, the most of any base in the US.

After the Great War, the base continued to train officers, but with a lack of enemy forces on the horizon until the late 1930s, and various budget cuts, the base sat peacefully, if not in ignorance of its approaching irrelevance. It briefly served as the headquarters for the First Air Force, and later as a NIKE surface-to-air missile base to defend against Soviet attacks, but never bested its early 1900s glamor.

The base was slated for deactivation at the nearest opportunity, its revolving door of classes, programs, and initiatives failing to stay cemented to the island base. It was finally deemed to be excess by then-Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who officially shunned the base in November of 1965, a year short of its centennial. And so the fun began.

The island has become a place where grand ideas, exercises in American ingenuity, and the hopes of Disney, Donald Trump, and developers alike have gone to die. Now closed for military activity, David’s Island still had dozens of well-built and maintained buildings. It was briefly used by youth groups to host getaways and orienteering exercises, but nothing of great magnitude or investment came to fruition. And so the zoo arrived…

On August 10th, 1966, less than a year after deactivation, it was reported that “Noah’s Ark Barge On Way To [Fort] Slocum.” Fifty-five animals, direct from Mombasa, were dumped off on Fort Slocum after contracting hoof-and-mouth disease on their way across the Atlantic. Aboard the voyage were giraffes, elephants, zebras, birds, rhinoceros, gazelles, and umpteen other beasts slated for delivery to thirteen American zoos. Unable to enter the US mainland, the animals were exiled to David’s Island to the dismay of locals, who especially feared the water buffalo, as they were capable of swimming the short distance to shore, though none made the journey. The island played zoo for the ensuing months until the animals were admitted to their respective homes.

The US government, now well-worn after over a century of caretaking, looked to absolve itself of the island. Following a row between the county and city over rightful ownership, New Rochelle purchased the land and announced it was open for development plans from any (humans) interested. The island is a near dream-come-true solution to the densely packed and nearly used-up lands of southern Westchester. The open-for-ideas 78-acre territory, about the size of 35 city blocks, intrigued the likes of Disney, various universities, the National Park Service, and Con Edison, who purchased the island and buildings for three million dollars in 1968.

Armed with plans to build the world’s largest and most ambitious nuclear power plant capable of powering hundreds of thousands of homes, Con Ed worked to resolve public pushback. Their grand plan, which would require little from the city, while pumping $250,000 a year into the city’s coffers, did not bode well with nearby residents. By 1973, Con Ed realized the writing on the wall, and sold the island back to New Rochelle in 1976 for just one dollar, taking their plans to Indian Point.

Stuck again with the old fort, and three million dollars richer, New Rochelle tried once again to dispose of the island, partnering with Xanadu Properties Associates, who dreamt up plans of an island paradise. Their plan, calling for 2100 condos, private beaches, a bridge, pools, and an 800-boat marina, was pitched as the final solution to this everlasting island saga. For ten years, Xanadu worked to overcome funding, environmentalists, New Rochelle residents, and various opposition groups, all to no avail. The lack of public access and community benefit killed the project for good, and come 1992, the island was up for grabs once again.

Trump Island, or so Donald Trump thought, would be the name of the future President’s next grand real estate adventure. The island, now having been a fort, hospital, zoo, training center, and nearly a power plant, was top of mind for Mr. Trump, who in 1993, paid New Rochelle $500,000 to gain the right to be the exclusive developer of the island. He planned to put up four towers, twenty-two, and fifty-five stories high, with the absolute necessities in the name of helipads, ferries, and a marina added, all to the tune of 700 million dollars. Unable to resolve disputes over sewage and property dimensions, Trump backed out of the project and demanded his half-million-dollar payment back to no avail. (He would go on to get a 40-story tower with his name on it downtown years later.)

New Rochelle was now desperate to sell or develop the island, its buildings continued to crumble, its asbestos and roofing wafting into the sea, and growing angst that the island may never be settled. Proposals were fielded for a hotel, theme park, science center, marina, and housing, but all fell to ashes, and then to dust. New Rochelle could not settle on a plan that appeased environmentalists, conservationists, residents, boaters, and the city’s budget.

Westchester County still soured over their loss of the island and sensed opportunity amidst the loss of various projects. County officials offered New Rochelle six million dollars to sell and were given the exclusive right to purchase the island. This plan was highly publicized and seemed like an endpoint to the nearly 40-year saga to bring peace to the island. Nearly set to finalize the deal, Westchester backed out, scared off by the estimated twelve million additional dollars it would take to clear the island of the rubble.

Beaten, broken, and bloated still with an unsellable island, New Rochelle, with the help of the Army Corps of Engineers, cleared the island of its dozens of buildings and attempted to make the island as attractive to development or parkland as possible. To the tune of twenty-six million dollars, fourty times what the island cost in 1968, the land was raised and made ready for the next chapter in its long history.

This chapter has yet to be finished as the island remains untouched since its clearance in 2008. What it lacks for in construction it makes up in ambition, its large, lush, and flat platform of earth eagerly awaiting its next order. The island, a siren song alluring developers and disappointment in equivalent droves, remains ivy-packed and attractionless, not more than a stone’s throw away from the most densely packed city in America.

Enjoyed this article? You’d also like 15 Of NYC’s Other, Lesser-Known Islands and Photos: Inside NYC’s Abandoned Fort Wadsworth On Staten Island

Subscribe to our newsletter