Nearly 1,000 men, women, and children are believed to rest below the pavement of the parking lot at 1440 Forest Avenue in Staten Island. Before being paved over in the 1950s, this area was the site of the Second Asbury AME Church and accompanying Cherry Lane Cemetery, an African burial ground that served as the final resting place of local African American residents and former slaves. Long forgotten in the records of history, Cherry Lane is now getting some of the recognition it deserves.

On May 20th, a determined crowd braved the rain and gathered at the site to attend a street co-naming ceremony. The street that runs adjacent to the Cherry Lane site, Livermore Avenue in Port Richmond, is now also known as Benjamin Prine Way.

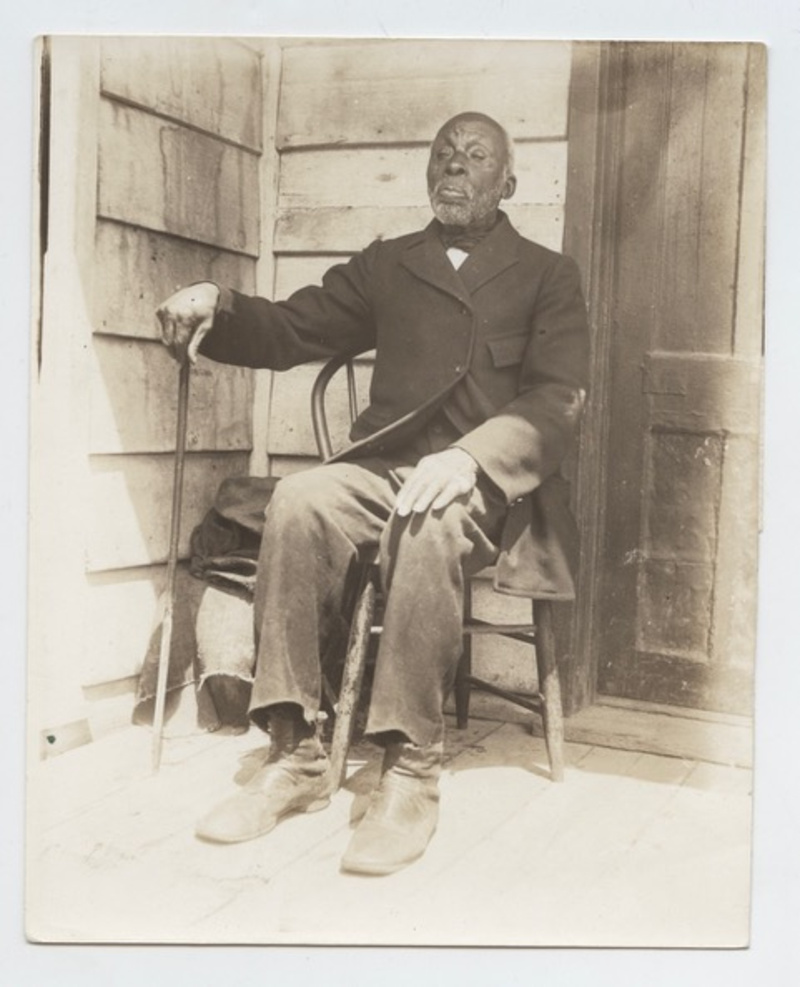

Benjamin Prine was the last living person on Staten Island to have been born into slavery. He was reportedly 106 years old at the time of his death in 1900. Though forgotten in the afterlife, he was a well-known figure in the 19th century. When he died, he received an obituary in the New York Times and in newspapers in other states.

Born in 1794, Prine was enslaved by the Van Pelt family and freed by the Northern Slave Act in 1822. His obituary notes that he played with Commodore Vanderbilt – another Staten Island resident – when they were children, helped to protect the Van Pelt family during the War of 1812, and was the first stagecoach driver on Staten Island.

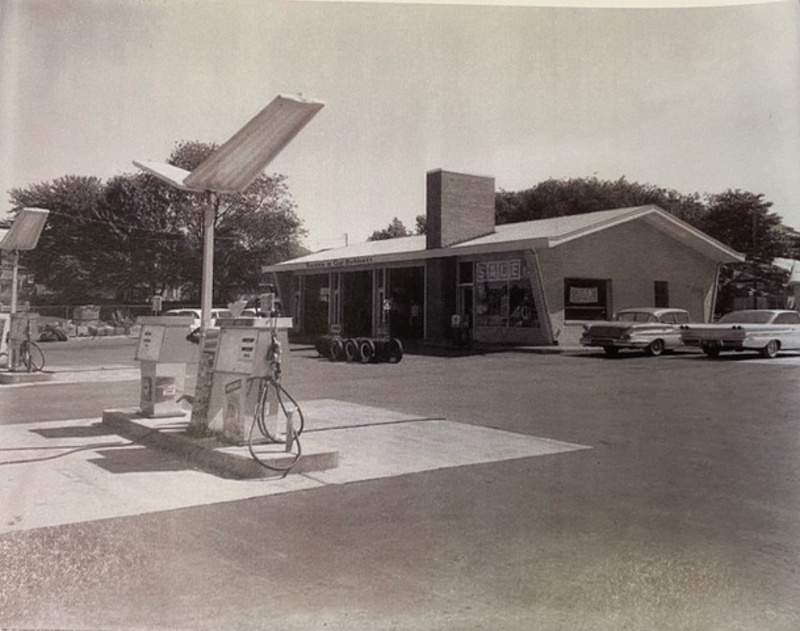

At the street co-naming event, many of Prine’s descendants were in attendance. The family members, many of whom had never met each other before, came from all over New York and New Jersey and from as far as Cincinnati. Many had grown up on Staten Island before moving elsewhere and knew the Cherry Lane site only as a gas station or shopping center. They were unaware of their own family connection until they were contacted by filmmaker Heather Quinlan.

Quinlan and her crew captured the memorable meeting for her forthcoming documentary about the history and rediscovery of Cherry Lane cemetery, Staten Island Graveyard. Quinlan first came upon the story of Cherry Lane several years ago while researching New York City cemeteries for her next project. There were many features of the story that made her want to learn more, share it with others, and take action.

One significant piece of the story that stood out to Quinlan is that the “obliteration [of the cemetery] happened in the 1950s, not the 1850s, which is when most people assume,” she told Untapped New York. Quinlan also wanted to help set the record straight about slavery in the North. “We take in the huddled masses, and the Southerners enslaved people on plantations and we had to fight a war to get them to stop,” she says is a common belief, “but in reality, New Jersey didn’t outlaw slavery until 1866, so we have a lot to answer for.”

The Second Asbury A.M.E. Church which formerly stood on the site was torn down by the 1880s. An estimated 90 to 1,000 men, women, children, and babies are believed to have been buried in the accompanying cemetery. Many were local oyster fishermen since freed African Americans were able to own their own boats on Staten Island, and other internments, like John Keys, were slaves who escaped from states like Maryland and Virginia.

After the church was torn down, a board of trustees was appointed to oversee the cemetery, but there were no funds to maintain or protect it. There were no headstones at the cemetery and any wooden crosses or other temporary memorials were eventually obscured. Throughout the early 20th century, the cemetery appeared, on the surface, to be an empty lot.

In the 1950s, as the development of the neighborhood increased and the area became commercialized, a real estate developer discovered that the cemetery board owed thousands of dollars in taxes on the property. The city sued the board for the money owed and when the board wasn’t able to pay, the site was auctioned off. In court documents, the city writes that “The property is vacant and unoccupied. There are no headstones on the property and no evidence of anyone ever having been buried there, nor any evidence to show that the same ever was cemetery or burial ground.”

This finding contradicts maps of the area that clearly mark the church and burial site. By the 1960s, a gas station was constructed at the site, but no bodies were ever moved. In 2005, when the site was sold to the current owner, there was no mention of a former cemetery on the deed.

Over the years, there have been some efforts to have the site recognized as a cemetery. Borough Historian Richard Dickenson successfully petitioned for a commemorative plaque at the site. In 1991, a plaque was put inside the lobby of First Nationwide Bank, now Santander Bank. When the bank switched owners, however, the plaque was lost.

The street co-naming and Quinlan’s film mark a new revival in the efforts to have Cherry Lane recognized as a cemetery. Santander Bank will soon unveil plans for a memorial garden. The bank also funded the planting of a Cherry Tree in a previously empty tree bed on the site, a nod to Forest Avenue’s previous incarnation as Cherry Lane. Next, Quinlan and the descendants hope to be able to perform a ground penetrating radar survey to see the bodies that remain and to hopefully one day give them a proper burial.

“My goal with this film is to have it set a blueprint for other people who will undoubtedly come across this in their communities with their own families and their own ancestors,” Quinlan shares, “to show how they can affect change.” The story of Cherry Lane is unique in that the cemetery has already been paved over, but Quinlan believes there is still good that can be done. “It’s one thing if there was construction and we found the bodies, but the worst has been done now, so how do we go back in time? It can’t be a cemetery anymore, but we can do something different, something better.”

Next, check out NYC’s Smallest Cemeteries by Number of Internments and NYC Sites That Were Former Cemeteries