Forget Thanksgiving; in post-Revolution New York City, the biggest November celebration was Evacuation Day. Observed on November 25th, this early American holiday marked the date on which the last British soldiers left Manhattan after the Revolutionary War in 1783. Once the British were out, triumphant Americans marched through the streets and raised the new flag, though not without some difficulty. For more than a century, Evacuation Day overshadowed Thanksgiving and was celebrated more fervently than the Fourth of July in New York City. Today, while our fall festivities are more concerned with feasting on turkey rather than expressing our patriotism, many New Yorkers still honor the memory of Evacuation Day.

On that joyous Tuesday in 1783, New Yorkers welcomed the new American regime. New York Governor Clinton and the victorious General George Washington paraded through the streets of Lower Manhattan. Accompanied by an array of soldiers and officials, and surrounded by throngs of excited onlookers, Clinton and Washington marched from Bull’s Head Tavern in the Bowery to Cape’s Tavern on Broadway and Wall Street. Troops continued marching to Fort George to take down the British flag and raise the American one.

On our upcoming Evacuation Day live stream, join Untapped New York’s Chief Experience Officer Justin Rivers as he retraces the route, pointing out historical sites along the way! This virtual livestream is free for Untapped New York Insiders! Not an Insider yet? Become a member today and gain access to member-exclusive experiences, both in-person and online, as well as our archive of 200+ on-demand webinars. Use code JOINUS for your first month free!

At Fort George, the celebrations hit a snag. Before the British made their departure, someone had the idea to grease the flagpole and remove the halyards, the ropes used to raise and lower the flag. Many failed attempts were made to bring the British flag down, and there were cries to cut down the flagpole. Finally, Sergeant John Van Arsdale had a clever idea that saved the day. The story goes that Van Arsdale fashioned himself a pair of wooden cleats and climbed the pole. Upon reaching just high enough, he tore down the Union Jack and replaced it with Betsy Ross’s stars and stripes. While he did use some inventive techniques to get to the top, an account of the day’s events written by Van Arsdale’s grandson notes that he had at least a little bit of help from a ladder that was eventually brought to the site. The Alexander Hamilton Custom House, home to the National Museum of the American Indian, now stands at the old Fort George site.

Evacuation Day celebrations raged on for days as the American flag waved over Manhattan. After the parade on the first day, Governor Clinton hosted a 120-person dinner at Fraunces Tavern, where many toasts were made in honor of Washington and his men. The party didn’t stop until Washington left New York City on December 4th. On that day, Washington said farewell to his troops at Fraunces Tavern then headed to Whitehall Wharf to catch a barge across the river to Paulus Hook, (now Jersey City) New Jersey. From there, he traveled on to Annapolis to meet the Continental Congress.

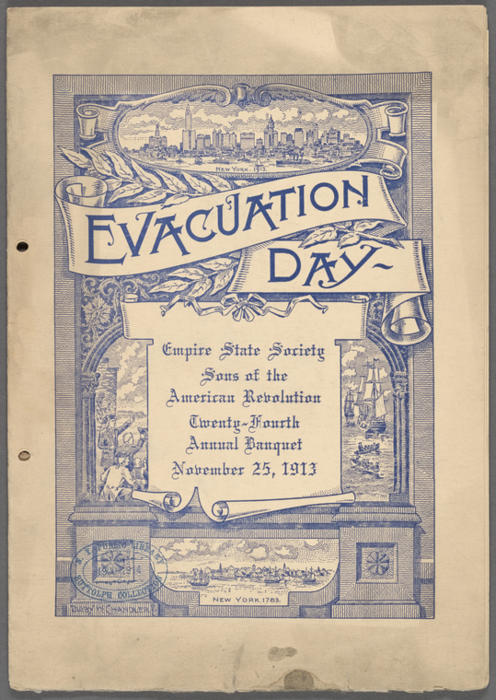

An enthusiastic observance of Evacuation Day in New York City continued through the early 20th century. In the early 1800s, November 25th was an official school holiday. Throughout the city, November 25th was celebrated with parades, fireworks, military drills, lavish dinners, recreations of Van Arsdale’s flagpole climb, and flag-raising ceremonies often led by Van Arsdale’s descendants. In the New York Public Library archives, you can see banquet menus for Evacuation Day dinners hosted by organizations like the Sons of the American Revolution at iconic New York hotels such as the Waldorf Astoria and the Plaza. The revelry rivaled that of the Fourth of July.

As the 19th century drew to a close, however, observance of Evacuation Day began to wane. By the late 1800s, those who had witnessed the first Evacuation Day celebrations were no longer around, and subsequent generations didn’t uphold the tradition. That duty fell mostly to veteran groups. This holiday wasn’t celebrated anywhere else in the United States except New York City (though Massachusetts has its own Evacuation Day in March), so it never gained national support. Another contributing factor to the decline of Evacuation Day was the advent of World War I. Britain was our ally in that conflict, and many considered it poor taste to continue celebrating their defeat as our enemy. With the dawning of a new century, new traditions began to take hold. Another November holiday, Thanksgiving, became the dominant November holiday and the Fourth of July served as a day to express our patriotism.

The last grand Evacuation Day celebration took place on its centennial in 1883. The celebrations included a parade of 20,000 marchers, ships in the Hudson and East Rivers, banquets at Madison Square Garden and Delmonico’s Restaurant, and fireworks. On this occasion, a statue of George Washington was unveiled on the steps of Federal Hall. The last official Evacuation Day was celebrated in 1916.

Despite Evacuation Day’s slip into obscurity, it is still observed by some to this day. In 2017, there was a street dedicated to the holiday. Evacuation Day Plaza is marked with an illuminated street sign, put up by The Alliance for Downtown, at Bowling Green. Every year, Fraunces Tavern commemorates the holiday with a special event, often featuring performances by the uniformed Fife & Drums of the Old Barracks, and discounted admission to the museum. While Evacuation Day has largely been forgotten and overshadowed by eating turkey, giving thanks, and catching deals on early Christmas gifts, it remains a uniquely New York part of America’s revolutionary history. And why not give yourself another reason to party this November? Celebrate this obscure holiday with Untapped New York Insiders on November 21st by joining us for a virtual live-streamed walk along Washington’s parade route!

Next, check out 10 Fun Facts About George Washington’s Inauguration on April 30, 1789 and Find the Remnants of King George III’s Statue, Toppled in Bowling Green in 1776