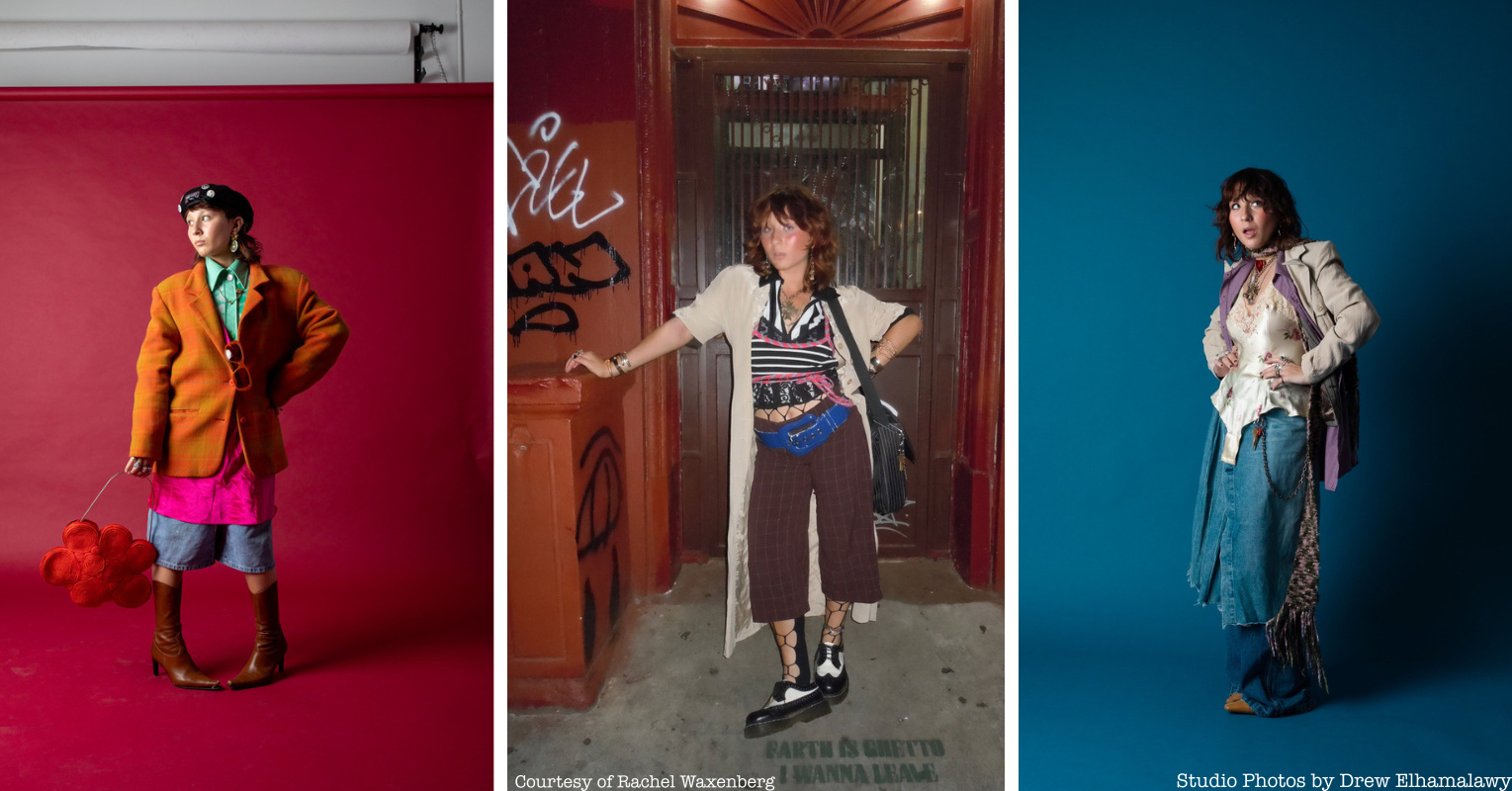

Many of us put on jeans, one leg at a time. Rachel Waxenberg, a Bushwick-based stylist, is keen on wearing her jeans as a scarf or occasionally putting her arms through the pant holes.

Waxenberg describes her style as sustainable maximalism, “I layer and piece together the unseen, wearing like trousers as a shrug or a blazer as a skirt.” As ridiculous and frankly unpractical as it may sound, Waxenberg isn’t the only one adapting this style. The viral “Bushwick” aesthetic is the latest fashion trend emerging from the gentrified streets of Bushwick.

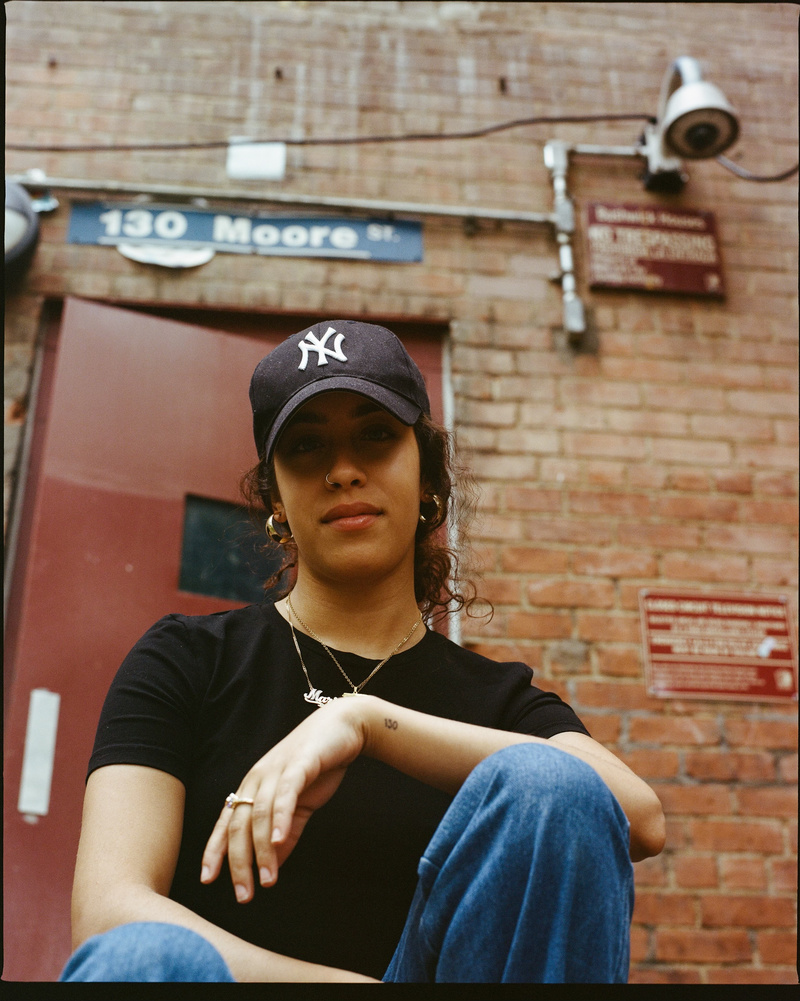

While some find the trend amusing, others are disturbed. “Aesthetics are dangerous,” says Mariah Espada, a third-generation Bushwick native. A community once riddled with crime and drug use, Bushwick is where Espada remembers her brother’s tilted Yankee-fitted cap and grandfather, Papi Cheo’s mechanic’s jumpsuit.

Bearing no relationship to Bushwick’s Puerto Rican or other communities who have lived in the neighborhood for decades, the Bushwick style is the latest installment of the early 2000s hipster aesthetic of Williamsburg. Native Bushwick residents are now taking to social media to denounce the style.

“Taking everything a little bit too far”

Marked by the unconventional use of layers, an erratic combination of fabrics, and the occasional vintage designer bag, the “Bushwick” style, as fashion content creator Sam Dean notes, “is too much into the y2k aesthetic…taking everything a little bit too far.”

As a newcomer to the city, Dean picked up on the trend after her satirical “How to dress like you’re from the Lower East Side” TikTok video went viral. Once Dean saw the demand for a Bushwick version of this niche neighborhood aesthetic, she quickly picked up on the look. “It’s that artsy type who wants to look grunge, but do it in the most expensive way possible,” Dean noticed while observing the style of Bushwick residents at a coffee shop.

Online, the style is all over the place. A self-proclaimed Bushwick Princess Diana rocks a distressed beanie, and the whimsical 2020 Vogue cover shoot, Playtime with Harry Styles, is synonymous with the Bushwick aesthetic.

Without a specific term to describe the style, Bushwick, according to Google, is an “edgy and increasingly hip” area in northern Brooklyn. Many online perceive the aesthetic as embodying the stereotype of the latest wave of transplants and their zest for the grimmy fortress that is New York City.

Native New Yorkers and the fashion community, however, find little humor in the style. Comments under Dean’s Bushwick video read, “Transplant fashion. Not native.” The fashion girlies even claim New York Fashion Week is dead because of Bushwick style, and as Bronx-based fashion designer Rafa says, “I’m not mad at it but would rather see more originality. If your fit is trash but it’s genuinely your style, I can appreciate and respect it more.”

“A hodgepodge of working-class people wearing whatever it is that they could afford”

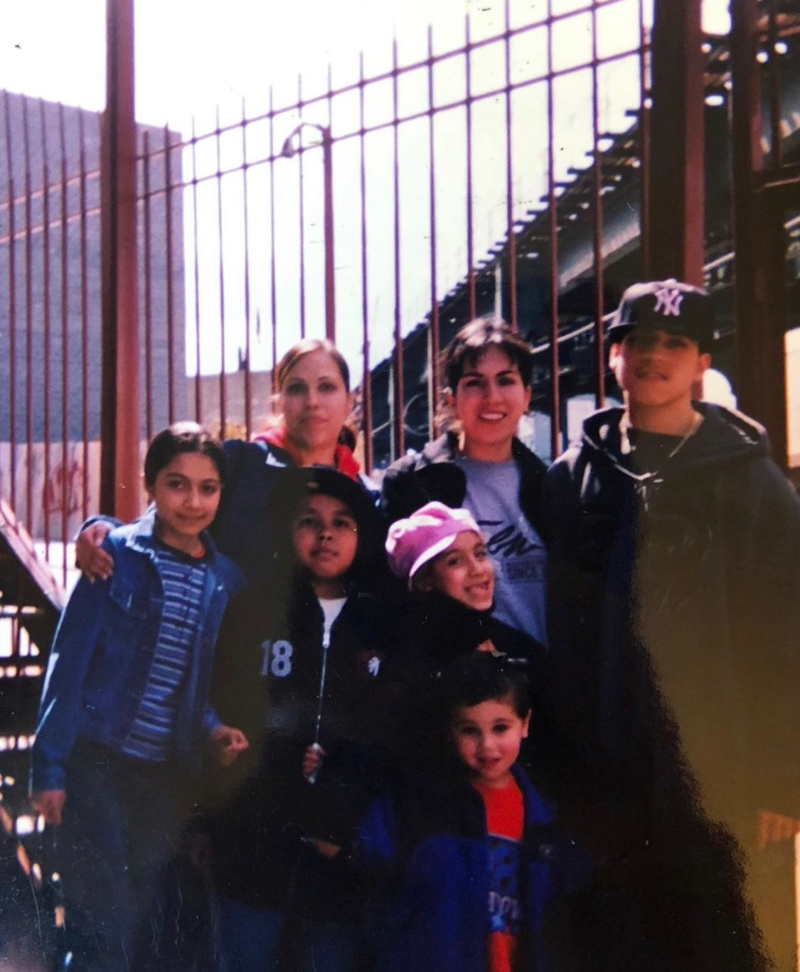

A Nuyorican love child, if there ever was, Espada knew nothing of aesthetics and only of her hood. Espada’s parents, just teens, were second-generation immigrants from Puerto Rico figuring out their way in the streets of Brooklyn when they had Mariah.

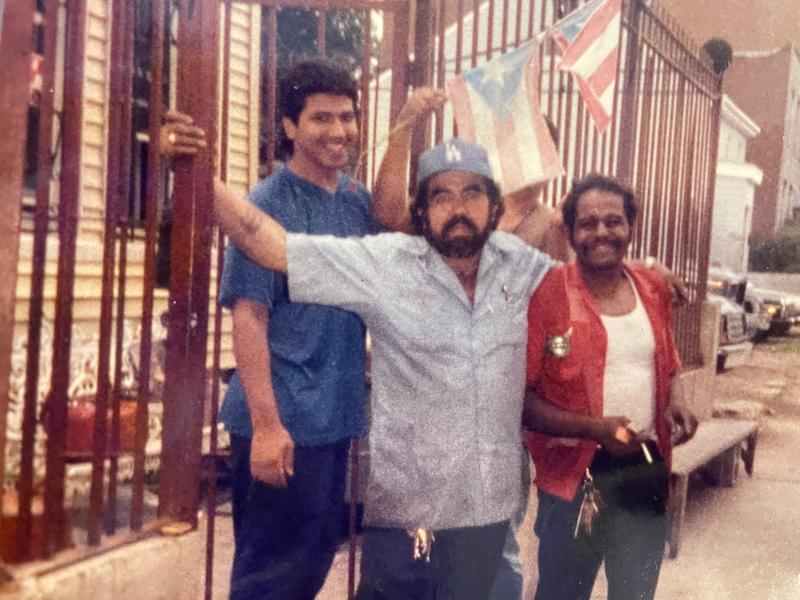

“I have fond memories of, my brother, wearing his fitted caps, sneakers, and Coogi jacket. But I also just have memories of seeing my abuelo, he was a mechanic. So, seeing him in his Carhartt jacket and a bunch of keys,” she says. “My mother worked at the post office, and I always visually remembered her wearing her USPS uniform. It was just a hodgepodge of working-class people wearing whatever it is that they could afford.”

A common thread among densely populated Black and Brown, low-income communities in New York, style is dictated by where your generation sits in the diaspora. “Young people in Bushwick who are like four generations in migrating from San Juan might express themselves and look more like they’re similar to communities in the Heights or the South Bronx. You’re not necessarily recently arrived but you know, you’re just also dressing the way that like a third-generation Puerto Rican kid would dress rather than someone who’s just off the island,” says Dominique Jean-Louis, Chief Historian of the Center for Brooklyn History.

A mid-1800 Dutch settlement, Bushwick earned the nickname “Little Germany” for its breweries. Fast forward to the 1950s, and it became one of New York City’s biggest Italian-American neighborhoods. Soon after, economic challenges and demographic shifts, notably an influx of Puerto Ricans and African Americans, led to a decline in the white, non-Hispanic population to less than 40 percent. By the 1990s, Bushwick faced significant economic hardships, including a notorious drug market along Knickerbocker Avenue known as “The Well.”

“I’ve never felt so confident in my life”

In the hands of tech natives, the use of aesthetics is the latest lucrative tool in the fashion industry. Lisa Hopkins Newell, Adjunct Faculty of Fashion Studies at Columbia College Chicago, notes that the narrative one hopes to project from an aesthetic is instantaneous now. “If I post every day, you’ll get a community of people who think that’s you. So when I come from behind the screen on social media, and I start wearing this and I start acting the part… suddenly, that’s who you believe I am,” she says.

If Waxenberg’s fit-check videos on TikTok trigger a “what the f*** are you wearing?” comment, her style is about getting rid of the handbook. “I’ve never felt so confident in my life like in the last two years because I can walk out of my apartment, go to the supermarket in heels, and like no one’s batting an eye,” she says.

In contrast to what folks online believe are rich kids cosplaying as poor, Waxenberg attributes the style to being able to unearth hidden gems in thrift and vintage shopping. “You can look like you’re wearing these designer pieces but they’re all thrifted,” says Waxenberg. “I have a Dries Van Noten jacket and it’s my baby, my prize possession, but I got that little f***er for like so cheap at the thrift store.”

Vintage and thrift shopping is all the rage for Gen Zers and millennials. According to a 2023 Fashion Resale Report, the global secondhand apparel market is expected to grow 3 times faster on average than the global apparel market overall. Brooklyn alone has become the latest second-hand hot spot with thrift store chain L Train Vintage opening up its ninth store in Bushwick.

In the assimilation of originality, the paradox of the Bushwick aesthetic is one we’ve seen before. The early 2000s hipsters of Williamsburg, priced out of Manhattan, popularized the trucker hat and grew out their beards as a “f*** you” to the professional status quo.

People with a natural affinity for fashion and self-expression were flocking to the area and once the art scene trickled into Bushwick, so did the transplants. By 2021, there was a 20% decrease in the Hispanic population, a 7% drop in the Black community, and a 20% increase in the white population over two decades, per NYU Furman Center data.

“Mommy, they’re getting off after Manhattan”

Although many fashion critics were unaware of what was to come, Espada saw the rift first-hand commuting home from school in Manhattan on the L train as a kid in the early 2000s.

“Pre-iPhone, I was just sitting [on the L train] with my Walkman people-watching. Back in the day, it was more of like this hipster look…almost like a lumberjack aesthetic,” she says. “I’d be like, ‘Mommy, they’re getting off after Manhattan.’ In middle school, I’d be like, ‘Oh my God. they’re getting off on Lorimer.’ Then in high school, they’re getting off with us and now it’s like, oh my gosh, I get off and they’re staying on the train towards Canarsie.” Espada never imagined her rough neighborhood would transform before her very eyes.

Adorned with her nameplate necklace and Yankees cap, Espada is triggered by a light-hearted “Bushwick” aesthetic when she remembers Bushwick as a place riddled with violence. “I remember the first time I went to the bar Mood Ring, everyone was out, and I was trying to enjoy myself. I remember having this second layer of thought, ‘Oh, me and brother got mugged right at this corner.’”

Ready to serve the demands of the next generation of dreamers, the Bushwick aesthetic is what happens when a city built on the grit of low-income communities, no longer sees these residents as valuable.

“It used to be that city planners would use what they called ‘slum removal,’” says Jean Luis. “They would kind of say, ‘Oh, we’re just going to remove this area because no one’s living here and it’s not adding anything. Whereas now that we have more mechanisms for people saying that’s not what Bushwick is, or this is not who should be prioritized.”

Whether the trend is here to stay, Espada is using social media to remind the world that Bushwick is more than just an aesthetic. Her passion project, HoodHistoryHere, is a TikTok account dedicated to the Puerto Rican history of Bushwick and Williamsburg. Espada wants newcomers to the community and fashion enthusiasts alike to acknowledge what once was. “I will show up to the point that I can and I want to but then, ‘can you meet me halfway?’”

Next, check out 10 Secrets of Bushwick