Photographer and filmmaker Moyra Davey is consistently praised for her interest in small, overlooked spaces and in subject matter that occurs on a microscopic and interior scale. But in her most recent film Les Goddesses, she expresses a self consciousness towards the very thing she’s known for. Her work examines the outmoded: a shelf full of record albums, old newspapers, magnified close-ups of the surfaces of pennies so scratched we can no longer recognize Lincoln’s profile. Images of dust, books, and handwritten notes recur, and her still life style seems to illustrate a common search for absolute meaning among spaces where we still only ever find objects. If the aim of today’s artist is no longer to make something noble, uplifting or even beautiful, Davey’s images suggest that the aim that remains is to represent a closely examined life.

The film explores her struggle to overcome a resistance to contributing to a world of images of dubious honesty, and an inclination towards retreating from this fixation on the minute. She is haunted by something she heard Jean Luc Godard say once on a French radio station. “Filmmakers who make installations instead of films are afraid of the real,” she quotes. When Davey’s career began in her early twenties she was more concentrated on portraiture, and now she expresses a struggle to return to street, vérité photography. She compares these recent still lifes, which take place in a controlled, malleable practice, with “rehearsed writing,” from notes and journals. The opposite being writing from the unknown, an image seized as it occurs, a movement as it moves, with little chance of revision.

In her essay, The Wet and The Dry, a companion to the film Les Goddesses, she refers to Walter Benjamin’s A Little History of Photography, “‘To do without people is for photography the most impossible of renunciations,’” she quotes. “Yet that abandonment is precisely what would begin to take place in my photographs over the next ten years, beginning in 1984, until my subjects constituted little more than the dust on my bookshelves or the view under the bed.” Throughout the film, she mentions concern about an inability to be present in any reality other than the reality of the camera. For a photographer, does the reality in the frame come first, or the circumstances which pushed the photographer into that frame? What is the difference between a tamer of time and a slave to time?

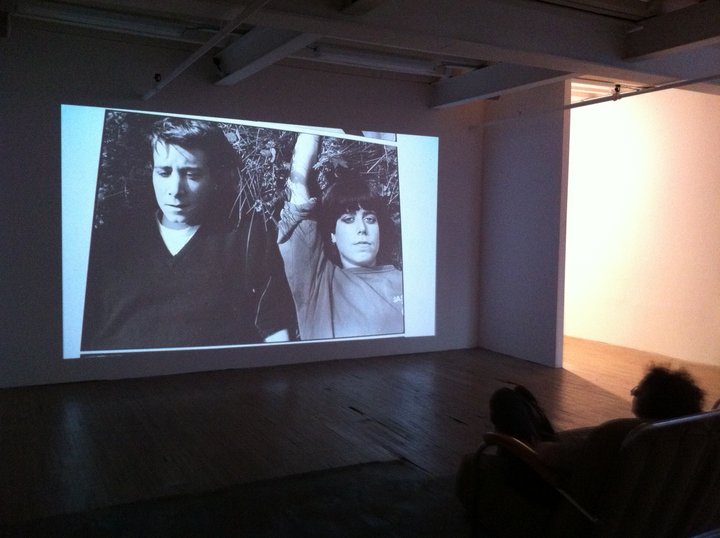

She hints at feeling blocked, and compares herself to a writer, but lacks a name for her obstacle. Writer’s block has a kind of legitimacy because of its common designation. This comparison is appropriate because it’s not quite right to think of Davey as solely a photographer. Her primary passion seems to be the act of reading. (She wrote a whole book on it in 2003 calledThe Problem of Reading.) In Les Goddesses, we see Davey pacing through her apartment with the camera pointed towards one seemingly random spot, as she walks in and out of the frame. She is walking and talking, opening the film with a voice-over that relates the experiences of eighteenth century radical philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft and her family. As she shares biographical information and reads passages from Wollstonecraft’s and her daughter, Mary Shelley’s diaries, Davey searches through portraits she’d taken of her own sisters years ago. She rifles through a pile of prints on her bed, her left hand presenting a succession of images, while her right hand holds the camera. The pictures are of a group of four women, of tattoos on their hips, and of individual poses. She ponders her sister’s illnesses and her own; encounters with pets and men and drugs and art. Davey collapses time by weaving her story with Wollstonecraft’s. She uses narrative transitions such as sharing this autobiographical information in conjunction with a background story about a collection of Wollstonecraft’s letters. “It was published in 1796, two hundred years before the birth of my son Barney,” she says, or tells us that Mary Shelley’s son Percy, unlike his literary and artistic parents, hated art museums. “Barney, aged thirteen, does not like art museums either. He says they instantly make him feel sleepy. He told me: ‘An ideal way to spend the day would be to drive to an airport and watch the planes take off and land.’”

Les Goddesses presents two important strategies in Davey’s investigation of herself and her work. Firstly, it creates a dialogue between Davey’s present work and her past’s. We see the portraits she used to make next to her new still lifes. She cuts to a shot of her hand brushing dust off a bookshelf, as if to symbolize another move away from images of this kind of surface. Secondly, the film and her monologue within it serve to connect Davey’s writing and reading practice to the memorializing practice of her photographic work. The film reexamines her process of looking.

I imagine that Moyra Davey takes pictures the way she reads, as if reading is making something, producing information rather than consuming. I consider seeing her photographs as a reader as well. For Davey, reading is not an escape from the self, but a performance of the self. If performance of the interior self means fitting ourselves into the exterior world, a good reader invents herself through the pages of a book. Davey leads us to ask not only what is the difference between a photographer and an essayist, or the difference between taking notes on an event or taking photos, but what is the difference between a reader and a writer?

The videocamera points out a window, or towards the corner of a room as we listen to Davey and she paces into and again out of the shot. She walks and talks as if she is thinking out loud. It reminds me of how we often take walks to tease out our thoughts, or of activities that we do with our bodies to help generate ideas. I know a high school English teacher who tells her students that if they’re having trouble getting into a book, they should put themselves in a physically uncomfortable position, sit in an uncomfortable chair, or make themselves cold. This way, the largest distraction is physical, separate from the task of the mind. I have a writer friend who says she writes the best sentences when she has to pee. I like this idea that distracting ourselves with our bodies actually helps our minds to focus. I know people who go for a run when they need to work out a problem; people who write not to document, but to think; people who take notes never intending to look at the notes. The act of note-taking (or picture-taking) simply sharpens the thinking, strengthens the consumption of the present.

Throughout Les Goddesses, Davey not only summons Wollstonecraft and Shelley, but other literary figures of the past. She ponders songs that have evoked memories otherwise forgotten, specific outside sensations that have brought on states of wellbeing such as letting water in a creek slip through her fingers. In Goethe’s Italian Journey, written in 1786, she notices that travel, a displacement in time and space and the ultimate fatigue it brings, also contributes to states of understanding, well-being, and “weightlessness.” She evokes Marguerite Duras’ dilemma, “To be without a subject for a book, without the idea of a book, is to find yourself in front of a book. An immense void.” Davey then notes that Duras “would go at it–writing and drinking–for days and nights.” Movement and consumption contributes to thinking. Duras was not afraid of “The Wet,” Davey’s term which comes to mean creative fertility.

“For Virginia Woolf, ‘being’ was writing and ‘non being’ was everything else,” Davey writes. “The thing is only alive (and by extension, I am only alive) while it is in process; and I’ve never quite figured out how to keep it ignited, moving.” One thing I notice about her work is that it feels incredibly urgent, as if collecting and writing and taking pictures is a vital physical process. I remember feeling an urgency towards writing and note-taking while taking care of my mother when she was ill, that I had never felt before. Writing would not only help my mind to work, but it would salvage my well being, and literally contribute to saving the life of my mother. Writing down names of medication, blood counts, her doctor’s names, lists of foods she craved, and lists of morphine induced dreams she told me, was a matter of life and death. Taking notes meant that I was acting towards a solution, and most of those notes were never even revisited. They merely helped me to get a grip on a challenging present. The thought crossed my mind one day while I was driving, (also a physical activity for courting thinking) of replacing the verb, “run” in that common, desperate phrase, “run for your life,” with “write.” Traveling, walking, reading, writing, drawing, listening to music, taking drugs, taking notes, taking pictures, are all altered physical states that may assist in the generation of ideas.

The final section of Les Goddesses is another photo-story called “Coda,” within which Davey remarks upon a recent development in her process of looking. On subway rides to the library, in search of Mary Shelley’s diary (among other books) she began to notice subway riders absorbed in writing of their own. Her narrative is now accompanied by a new series of still, color portraits. These new images are a combination of her close examination of the minute, and the present, street photography that had been a source of anxiety. She reflects on the paradoxical process that occurred while making this very film. “Just when I’d been writing about the disappearance of the figure from my photographs, I found myself taking street pictures again, in the dim green light of the Manhattan subway.” She tells us of children doing their math homework, a woman in orange velvet gloves writing in a diary with a yellow pencil, and of a man she saw twice hunched over a crossword puzzle in almost the same position. A city travels, thinks, moves, writes, with one woman reading it and taking pictures.

Hurry! Moyra Davey’s show, Spleen. Indolence. Torpor. Ill-Humour will only be up at Murray Guy in Chelsea until May 6th! Follow Untapped Cities on Twitter and Facebook.