New York is the ultimate city of water. With its 578 miles of shoreline, its tidal rivers and straits, bays, harbors, and ocean frontage, New York became fabulously wealthy over the centuries by ruthlessly exploiting the surrounding waters for shipping, commerce, and energy. For 300 years it has expanded its territory into the sea, building bulkheads and walls to protect the land from surges and storms, whose turbulence and unpredictability have served as a regular threat to the city’s welfare. But its shores were for industry, not people. In the name of protection, it closed off most of its dangerous, wild waterfront to New Yorkers until the late 20th century.

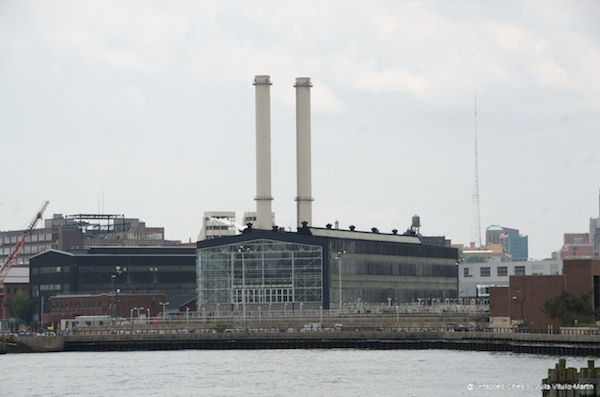

Today, New York has some 200 linear miles of shorefront public parks and spaces on private property and over 20 linear miles on public property. Yet it’s probably fair to say that New Yorkers dream of having access to it all. Nowhere is that truer than on the Brooklyn waterfront, once home to powerful industrial companies like Domino Sugar and Schaefer Beer, and to large swathes of property owned (and fenced) by quasi-public agencies like Con Edison, whose Farragut Substation is operational and probably indispensable, serving some 1.25 million people.

Then there’s the Port Authority, which in 2000 gave in to Brooklyn Heights activists and yielded 85 acres worth of long-defunct piers to build Brooklyn Bridge Park. Now a lovely 1.3-mile oasis floating above the East River, the park in 2006 “seemed a paradigm of cooperative, if prolonged, planning,” wrote Sam Roberts, noting that it was “isolated below the Heights and much of it cut off by the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.” Itself one of the most contentious infrastructure projects in New York history, the BQE seems rather charmingly modest and old-fashioned, in part because the neighboring park’s foliage helps mend the urban fabric, especially as seen from below. And, of course, it is topped off by the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, a walk so improbably idyllic that Hollywood uses it in every rom-com it can.

Brooklyn as Symbol of Reality and Resilience

So it was brilliant of Mayor Bloomberg to choose Brooklyn in all its astonishing complexity as the setting for delivering a major speech outlining his $19.5 billion plan to save New York from future storms. Defined in many ways by the ferocious East River (actually a strait) that separates it from Manhattan, Brooklyn operates much as if it were still an independent city keeping the tiger from crossing the bridge. Larger in population than Houston and Philadelphia (and dwarfing small cities like Denver), Brooklyn is increasingly formidable economically, nurturing and attracting start-up companies of all kinds. One of its economic centers is the 300-acre Brooklyn Navy Yard, which as the builder of battleships since 1806 symbolizes the old Brooklyn, and as an engine of current manufacturing growth, especially small companies, represents the new. Yet the Navy Yard campus is itself low-lying (a practical requirement for a shipyard), and suffered some $50 million in damage during Hurricane Sandy. Mayor Bloomberg delivered his speech in the magnificent Duggal Greenhouse, whose impressive come-back after Sandy is well told by Jason Sheftell.

To add further flair to his waterfront choice, Mayor Bloomberg suggested to his guests that they arrive by ferry, taking the round-trip journey between Manhattan’s Pier 11 on Wall Street and the Navy Yard, and cruising past a vivid section of the Brooklyn waterfront.

Concrete Recommendations for a Stronger, More Resilient New York

The 438-page report (SMRNY) has 250 recommendations for the city, but since the mayor took us to Brooklyn, I’m listing a few of his ideas for that borough. The Brooklyn waterfront is simultaneously strikingly built-up and strikingly low-lying, the East River ever close and high. Sections received a storm surge of up to six feet during Sandy. SMRNY proposes increasing coastal edge elevations, minimizing upland wave zones, protecting against surge, and improving coastal design and governance. Con Edison’s Farragut Substation, for example, which was nearly flooded by Sandy, sits in an area of growing risk from storm surge. SMRNY proposes that Con Edison consider flood walls along the perimeter of its property. (Walls will not be popular).

Because parts of Brooklyn Bridge Park sit below the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s base-flood elevations, SMRNY urges the park to invest in elevating its edge, creating additional rip rap to reduce the impact of waves, and selecting soils and plant materials for their resiliency. From the park up through DUMBO, the waterfront is susceptible to coastal flooding, which means that all building and renovation projects have to be judged by hurricane standards.

One of the first post-Sandy projects we’re likely to see designed and built to these new standards is the redevelopment of the Domino Sugar Factory. Two Trees Management principle Jed Walentas says of the redesign by SHoP Architects, “We’re raising and enlarging the park, which will be built with porous and storm resilient materials, and we’re pulling back the buildings from the edge.” The brand new quarter-mile bulkhead will be higher and stronger than the current one, and the front building edges will be more than 100 feet further inland from the water than the originally approved plan. The building footprints will be smaller, putting more bulk in the air, and the mechanicals will be lifted up out of the basements. By ripping out the cul de sacs and reconnecting the street grid, when and if it floods, Two Trees will ensure that water will be able to naturally drain back into the East River rather than pool on Kent Avenue or elsewhere in the neighborhood.

Mayor Bloomberg has laid out a commanding vision for securing New York’s waterfront heritage. It will be up to his successor–and New Yorkers–to forge the path forward.

Julia Vitullo-Martin is a Senior Fellow at the Regional Plan Association and director of its Center for Urban Innovation.

Get in touch with the author @JuliaManhattan.