A small printing press on Pearl Street is the birthplace of one of America’s most sacred and highly debated fundamental rights. In an upcoming virtual talk on the New York City roots of the first amendment, Untapped New York’s expert tour guide Mandy Edgecombe will trace the evolution of America’s right to freedom of the press from New York City’s first printing press to the groundbreaking libel trial of John Peter Zenger and the historic repercussions it had on America. Before he made his mark on history, Zenger was a mere apprentice in the shop of William Bradford, printer of the first newspaper and book in New York City.

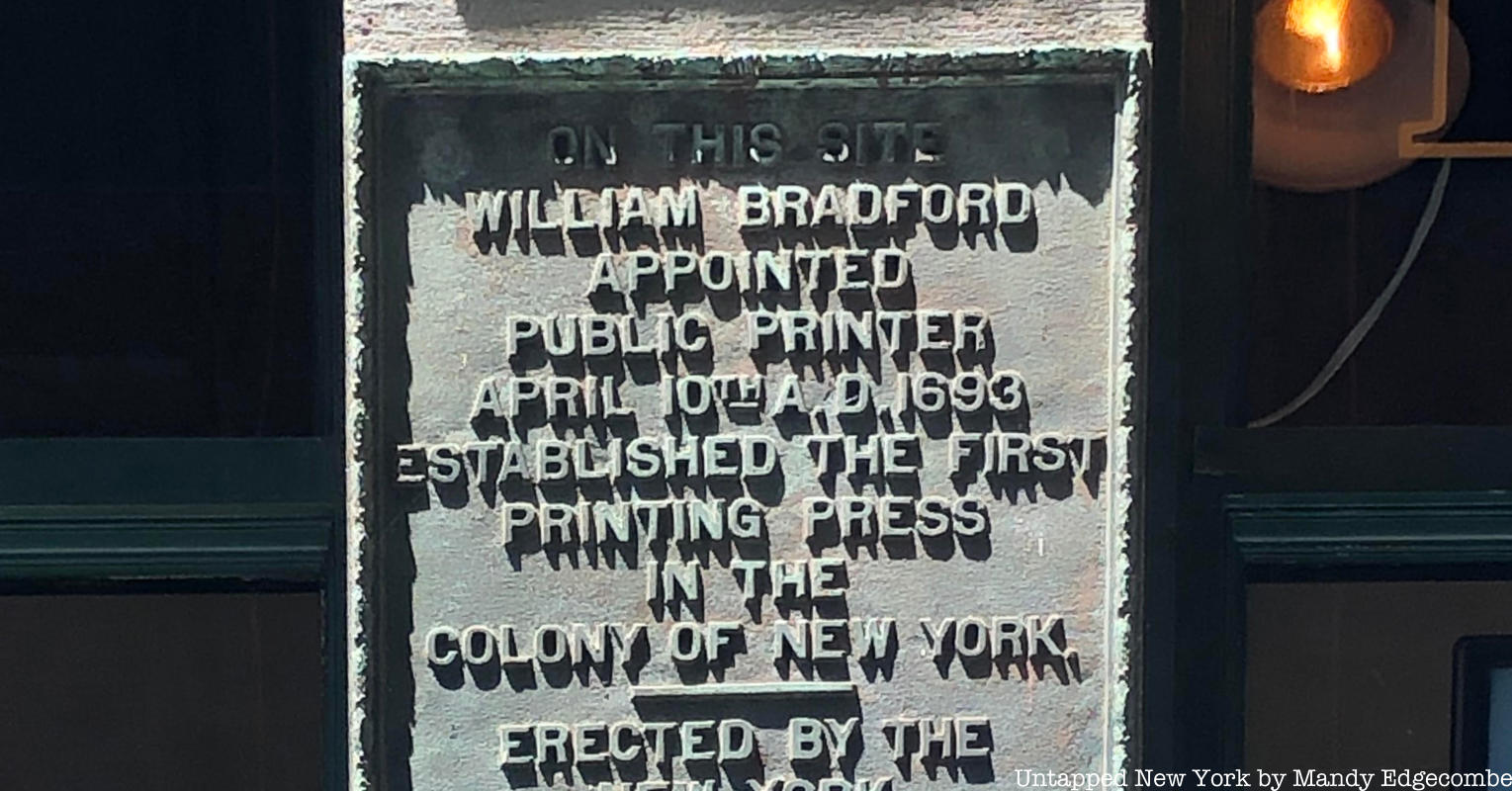

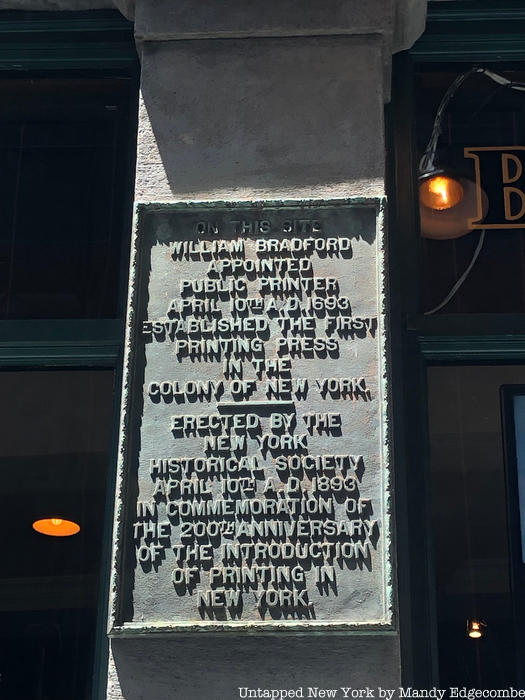

William Bradford emigrated to Pennslyvania after learning the printing trade in London. He settled in Philadelphia, where he established America’s first paper mill with William Rittenhouse (Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia is named for him). In 1693, Bradford was appointed as the Crown’s official printer of New York Province. He left Philadelphia for Pearl Street, where he set up New York City’s first printing press. Though the original building Bradford worked in was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1835, there is a plaque on the building at 81 Pearl Street (now a restaurant) that notes the location’s significance. On April 10, 1893, the New-York Historical Society erected the plaque in honor of the press’s 200th anniversary. Bradford is credited with printing the first book in New York as well as New York’s first newspaper, The New-York Gazette, in 1725. He worked in multiple shops around New York City, including on Stone Street, in Hanover Square, and near Maiden Lane.

It is at the printing press on Pearl Street where Bradford and John Peter Zenger’s stories merge. Zenger came to New York during a mass migration of Palatinate Germans in 1709. After an arduous nine-week journey across the Atlantic from England and a quarantine period on Governors Island, thirteen-year-old Zenger was sent to Bradford’s press, where he was indentured for several years. In exchange for labor, indentured servants received passage to America and often food, shelter, and clothing. After his indentured servitude was complete, Zenger moved to Maryland to start his own press. Bradford mentored many future printers but reportedly turned away one very famous name, Benjamin Franklin. Franklin approached Bradford looking for employment but was supposedly turned away because Bradford had slaves that could do the work for free.

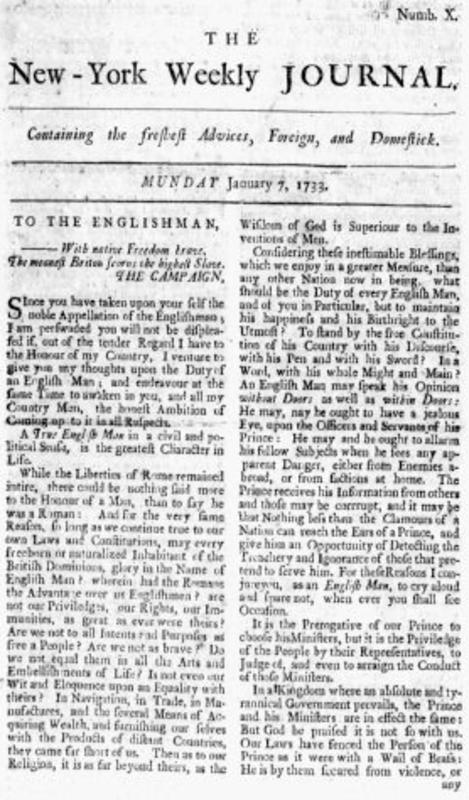

Bradford’s weekly publication, The New-York Gazette, was controlled by the British colonial government, represented by New York’s Governor William Cosby. It mainly contained boring and outdated news from England and was used mainly as a propaganda tool for Cosby to promote himself. In 1733, after returning to New York, Zenger, Bradford’s former apprentice, started his own opposing newspaper, The Weekly New-York Journal.

Image via Wikipedia Commons

Image via Wikipedia Commons

The Weekly Journal counteracted the Cosby-touting Gazette and criticized the governor’s corrupt leadership. Content for the paper, including political commentary and essays, was supplied by James Alexander, a lawyer who represented New York’s former governor Rip Van Dam. As a printer, Zenger facilitated the transfer of the author’s words to the page, but he did not create the content. Nevertheless, after a year of anonymously written attacks on the colonial government, Governor Cosby had Zenger charged with seditious libel. At that time, libel constituted anything negatively written about the government, whether true or not. The trial was held at Federal Hall.

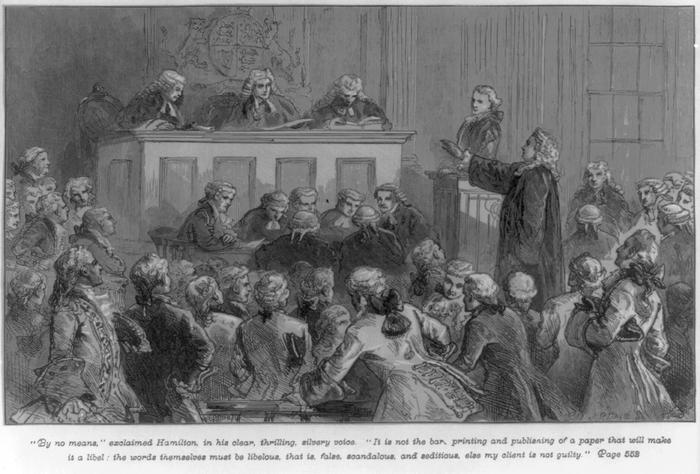

Though Bradford had been charged with libel himself in the past, he did not publically support Zenger. Bradford, as the Crown appointed printer of New York, relied on the government for his livelihood. Regardless of Bradford’s neutrality, Zenger and his lawyer Andrew Hamilton won the groundbreaking case, setting the foundation for a free press and further stirring revolutionary fervor. Speaking about the trial after it ended and defending his stance, Bradford wrote in his Gazette, “…I have according to my duty, sometimes printed in my Gazette some observations which the late Governor’s Friends, thought proper to make upon what the other Party printed against him, and for so doing Mr. Zenger, or some of the Party, have been angry with me…Reflected upon me and against my Gazette, insinuating that what I published was not true.” Bradford stated he would be “obedient to the King, and to all that are put in authority under him.”

Hamilton defending Zenger at trial, Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Hamilton defending Zenger at trial, Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Bradford’s Gazette would be printed through 1744, and The New-York Weekly Journal would be published until March 1751. Both Bradford and Zenger are buried at Trinity Churchyard. Learn more about John Peter Zenger’s famous trial and revolutionary New York City in our upcoming virtual talk on Tuesday, February 2nd.

Tickets to this live virtual talk are just $10. You can also gain access to unlimited virtual events per month and unlock a video archive as an Untapped New York Insider starting at $10/month.

BOOK NOW

Already an Insider? Register here!

Next, check out The Ghosts of Newspapers Past: 15 Former Locations of NYC Newspaper Headquarters and The History of NYC’s Newspaper Row, the Former Epicenter of News

This article was written by Nicole Saraniero with research by Mandy Edgecombe